Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

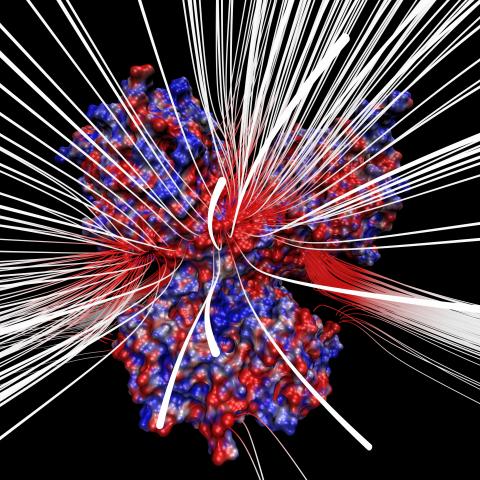

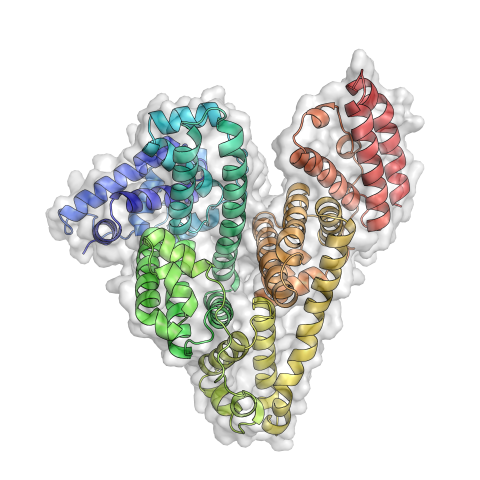

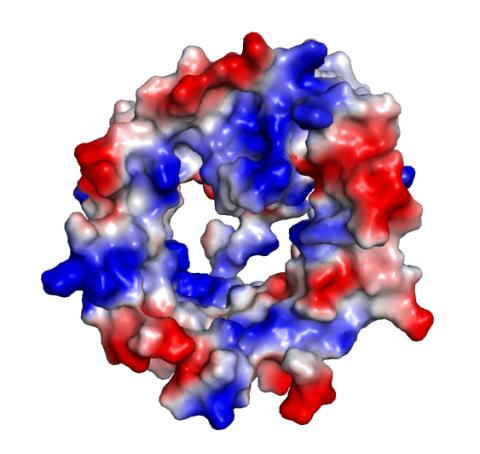

3658: Electrostatic map of human spermine synthase

3658: Electrostatic map of human spermine synthase

From PDB entry 3c6k, Crystal structure of human spermine synthase in complex with spermidine and 5-methylthioadenosine.

Emil Alexov, Clemson University

View Media

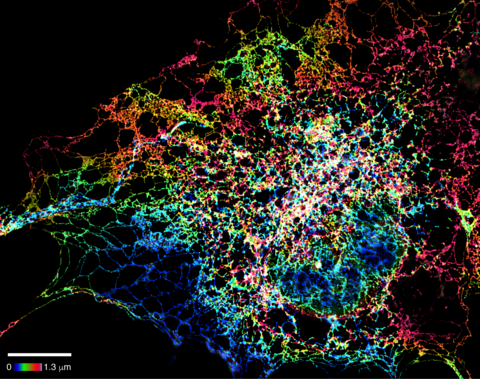

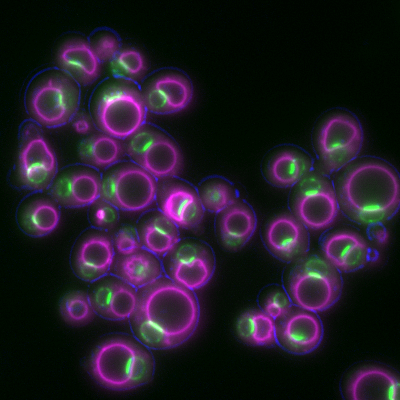

5855: Dense tubular matrices in the peripheral endoplasmic reticulum (ER) 1

5855: Dense tubular matrices in the peripheral endoplasmic reticulum (ER) 1

Superresolution microscopy work on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in the peripheral areas of the cell showing details of the structure and arrangement in a complex web of tubes. The ER is a continuous membrane that extends like a net from the envelope of the nucleus outward to the cell membrane. The ER plays several roles within the cell, such as in protein and lipid synthesis and transport of materials between organelles. The ER has a flexible structure to allow it to accomplish these tasks by changing shape as conditions in the cell change. Shown here an image created by super-resolution microscopy of the ER in the peripheral areas of the cell showing details of the structure and the arrangements in a complex web of tubes. Related to images 5856 and 5857.

Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Janelia Research Campus, Virginia

View Media

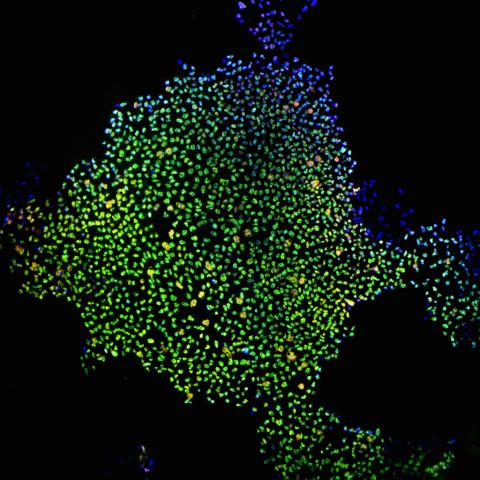

6986: Breast cancer cells change migration phenotypes

6986: Breast cancer cells change migration phenotypes

Cancer cells can change their migration phenotype, which includes their shape and the way that they move to invade different tissues. This movie shows breast cancer cells forming a tumor spheroid—a 3D ball of cancer cells—and invading the surrounding tissue. Images were taken using a laser scanning confocal microscope, and artificial intelligence (AI) models were used to segment and classify the images by migration phenotype. On the right side of the video, each phenotype is represented by a different color, as recognized by the AI program based on identifiable characteristics of those phenotypes. The movie demonstrates how cancer cells can use different migration modes during growth and metastasis—the spreading of cancer cells within the body.

Bo Sun, Oregon State University.

View Media

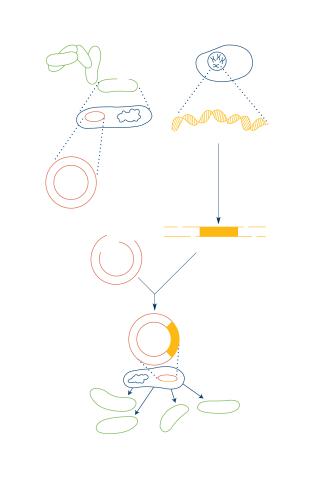

2564: Recombinant DNA

2564: Recombinant DNA

To splice a human gene into a plasmid, scientists take the plasmid out of an E. coli bacterium, cut the plasmid with a restriction enzyme, and splice in human DNA. The resulting hybrid plasmid can be inserted into another E. coli bacterium, where it multiplies along with the bacterium. There, it can produce large quantities of human protein. See image 2565 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

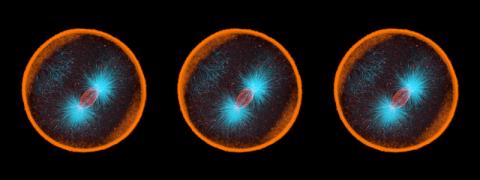

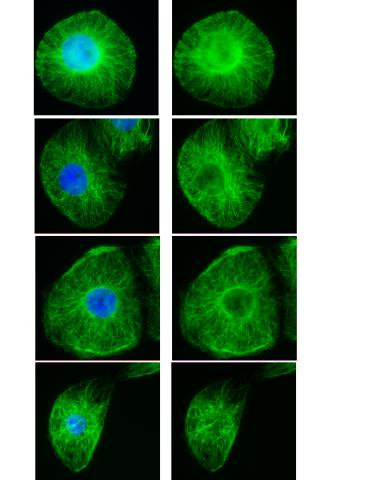

3443: Interphase in Xenopus frog cells

3443: Interphase in Xenopus frog cells

These images show frog cells in interphase. The cells are Xenopus XL177 cells, which are derived from tadpole epithelial cells. The microtubules are green and the chromosomes are blue. Related to 3442.

Claire Walczak, who took them while working as a postdoc in the laboratory of Timothy Mitchison.

View Media

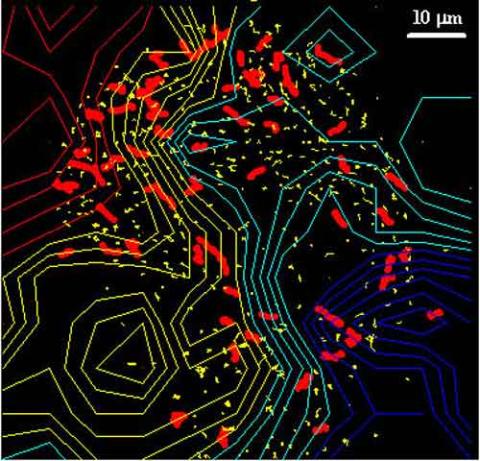

2310: Cellular traffic

2310: Cellular traffic

Like tractor-trailers on a highway, small sacs called vesicles transport substances within cells. This image tracks the motion of vesicles in a living cell. The short red and yellow marks offer information on vesicle movement. The lines spanning the image show overall traffic trends. Typically, the sacs flow from the lower right (blue) to the upper left (red) corner of the picture. Such maps help researchers follow different kinds of cellular processes as they unfold.

Alexey Sharonov and Robin Hochstrasser, University of Pennsylvania

View Media

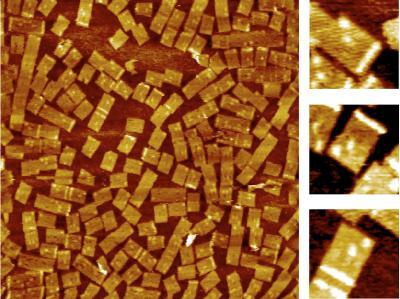

2455: Golden gene chips

2455: Golden gene chips

A team of chemists and physicists used nanotechnology and DNA's ability to self-assemble with matching RNA to create a new kind of chip for measuring gene activity. When RNA of a gene of interest binds to a DNA tile (gold squares), it creates a raised surface (white areas) that can be detected by a powerful microscope. This nanochip approach offers manufacturing and usage advantages over existing gene chips and is a key step toward detecting gene activity in a single cell. Featured in the February 20, 2008, issue of Biomedical Beat.

Hao Yan and Yonggang Ke, Arizona State University

View Media

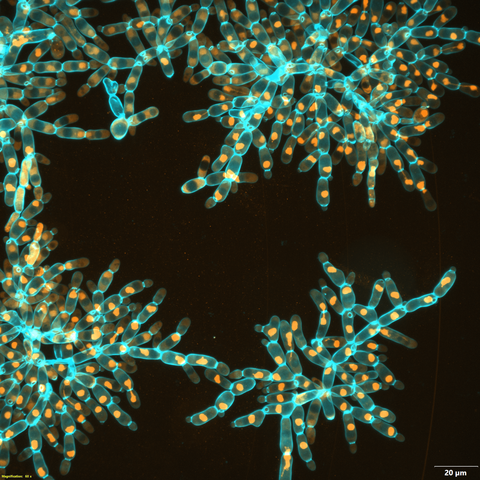

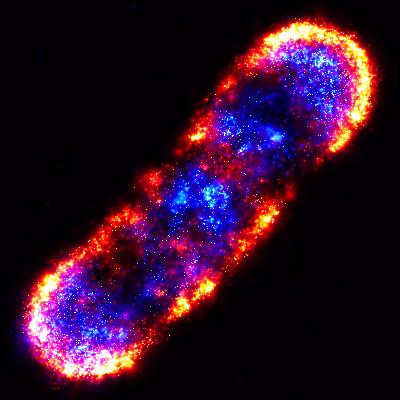

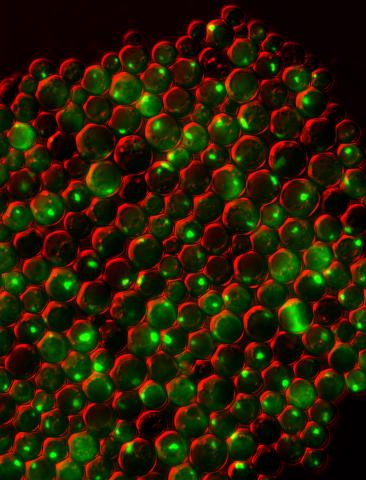

6971: Snowflake yeast 3

6971: Snowflake yeast 3

Multicellular yeast called snowflake yeast that researchers created through many generations of directed evolution from unicellular yeast. Here, the researchers visualized nuclei in orange to help them study changes in how the yeast cells divided. Cell walls are shown in blue. This image was captured using spinning disk confocal microscopy.

Related to images 6969 and 6970.

Related to images 6969 and 6970.

William Ratcliff, Georgia Institute of Technology.

View Media

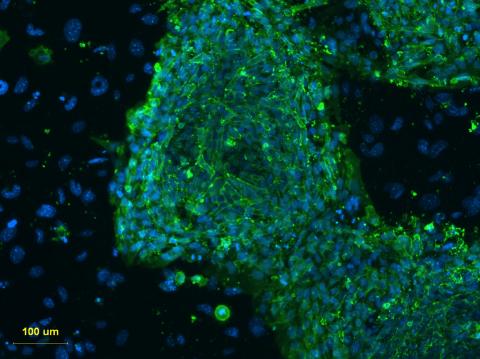

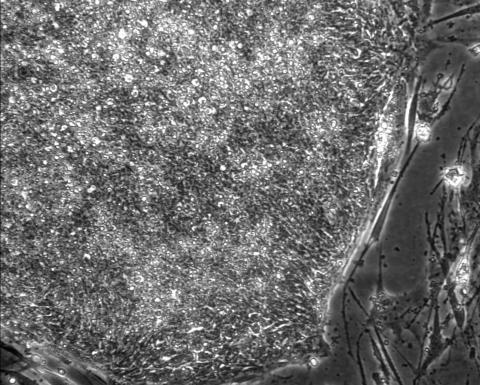

3274: Human embryonic stem cells on feeder cells

3274: Human embryonic stem cells on feeder cells

This fluorescent microscope image shows human embryonic stem cells whose nuclei are stained green. Blue staining shows the surrounding supportive feeder cells. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. See related image 3275.

Michael Longaker lab, Stanford University School of Medicine, via CIRM

View Media

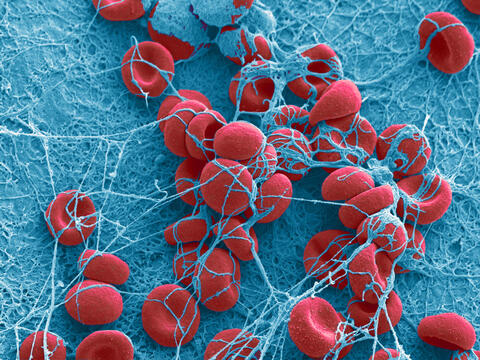

6573: Nuclear Lamina – Three Views

6573: Nuclear Lamina – Three Views

Three views of the entire nuclear lamina of a HeLa cell produced by tilted light sheet 3D single-molecule super-resolution imaging using a platform termed TILT3D.

See 6572 for a 3D view of this structure.

See 6572 for a 3D view of this structure.

Anna-Karin Gustavsson, Ph.D.

View Media

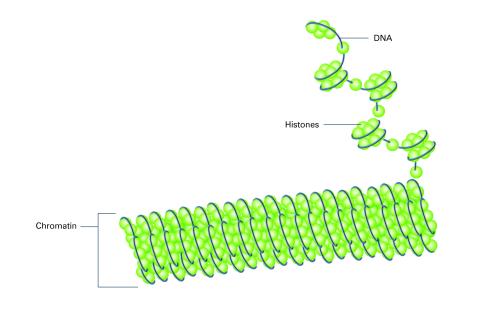

2561: Histones in chromatin (with labels)

2561: Histones in chromatin (with labels)

Histone proteins loop together with double-stranded DNA to form a structure that resembles beads on a string. See image 2560 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

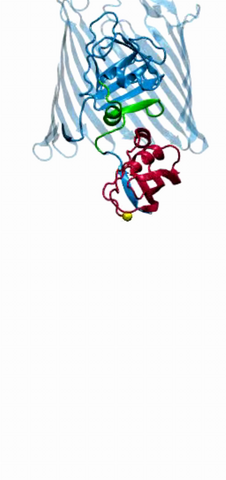

3787: In vitro assembly of a cell-signaling pathway

3787: In vitro assembly of a cell-signaling pathway

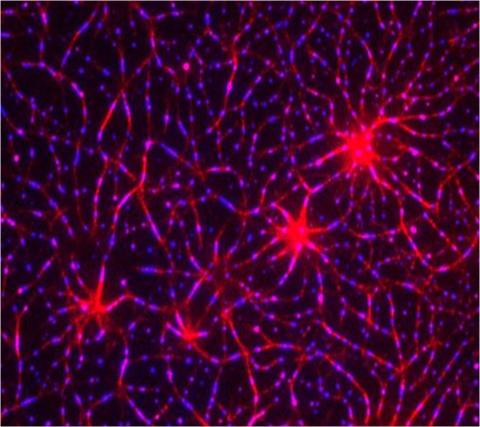

T cells are white blood cells that are important in defending the body against bacteria, viruses and other pathogens. Each T cell carries proteins, called T-cell receptors, on its surface that are activated when they come in contact with an invader. This activation sets in motion a cascade of biochemical changes inside the T cell to mount a defense against the invasion. Scientists have been interested for some time what happens after a T-cell receptor is activated. One obstacle has been to study how this signaling cascade, or pathway, proceeds inside T cells.

In this image, researchers have created a T-cell receptor pathway consisting of 12 proteins outside the cell on an artificial membrane. The image shows two key steps during the signaling process: clustering of a protein called linker for activation of T cells (LAT) (blue) and polymerization of the cytoskeleton protein actin (red). The findings show that the T-cell receptor signaling proteins self-organize into separate physical and biochemical compartments. This new system of studying molecular pathways outside the cells will enable scientists to better understand how the immune system combats microbes or other agents that cause infection.

To learn more how researchers assembled this T-cell receptor pathway, see this press release from HHMI's Marine Biological Laboratory Whitman Center. Related to video 3786.

In this image, researchers have created a T-cell receptor pathway consisting of 12 proteins outside the cell on an artificial membrane. The image shows two key steps during the signaling process: clustering of a protein called linker for activation of T cells (LAT) (blue) and polymerization of the cytoskeleton protein actin (red). The findings show that the T-cell receptor signaling proteins self-organize into separate physical and biochemical compartments. This new system of studying molecular pathways outside the cells will enable scientists to better understand how the immune system combats microbes or other agents that cause infection.

To learn more how researchers assembled this T-cell receptor pathway, see this press release from HHMI's Marine Biological Laboratory Whitman Center. Related to video 3786.

Xiaolei Su, HHMI Whitman Center of the Marine Biological Laboratory

View Media

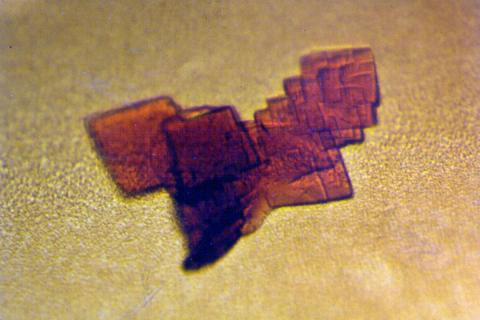

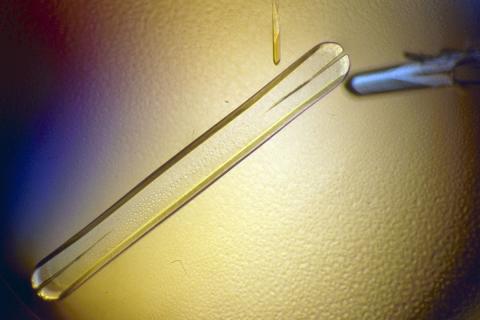

2392: Sheep hemoglobin crystal

2392: Sheep hemoglobin crystal

A crystal of sheep hemoglobin protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

6751: Petri dish containing C. elegans

6751: Petri dish containing C. elegans

This Petri dish contains microscopic roundworms called Caenorhabditis elegans. Researchers used these particular worms to study how C. elegans senses the color of light in its environment.

H. Robert Horvitz and Dipon Ghosh, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Media

2771: Self-organizing proteins

2771: Self-organizing proteins

Under the microscope, an E. coli cell lights up like a fireball. Each bright dot marks a surface protein that tells the bacteria to move toward or away from nearby food and toxins. Using a new imaging technique, researchers can map the proteins one at a time and combine them into a single image. This lets them study patterns within and among protein clusters in bacterial cells, which don't have nuclei or organelles like plant and animal cells. Seeing how the proteins arrange themselves should help researchers better understand how cell signaling works.

View Media

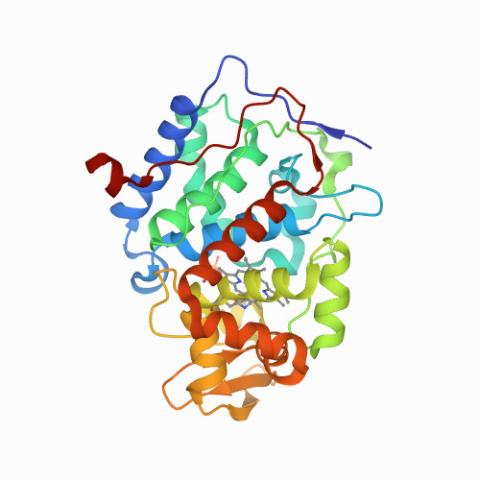

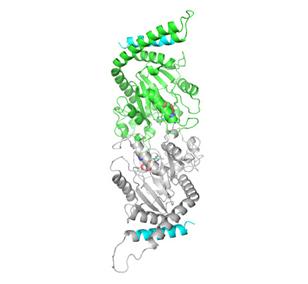

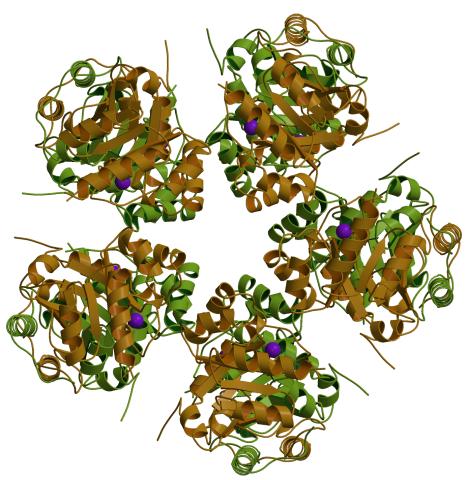

6762: CCP enzyme

6762: CCP enzyme

The enzyme CCP is found in the mitochondria of baker’s yeast. Scientists study the chemical reactions that CCP triggers, which involve a water molecule, iron, and oxygen. This structure was determined using an X-ray free electron laser.

Protein Data Bank.

View Media

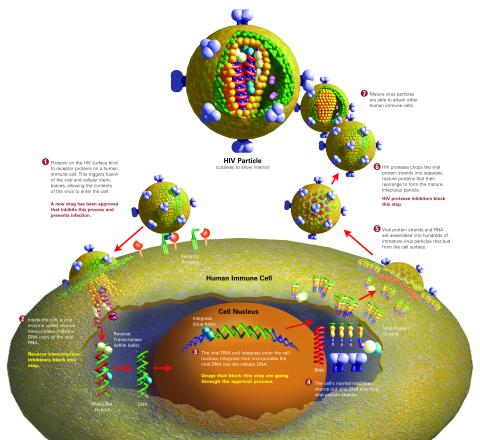

2515: Life of an AIDS virus (with labels and stages)

2515: Life of an AIDS virus (with labels and stages)

HIV is a retrovirus, a type of virus that carries its genetic material not as DNA but as RNA. Long before anyone had heard of HIV, researchers in labs all over the world studied retroviruses, tracing out their life cycle and identifying the key proteins the viruses use to infect cells. When HIV was identified as a retrovirus, these studies gave AIDS researchers an immediate jump-start. The previously identified viral proteins became initial drug targets. See images 2513 and 2514 for other versions of this illustration. Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2723: iPS cell facility at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research

2723: iPS cell facility at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research

This lab space was designed for work on the induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cell collection, part of the NIGMS Human Genetic Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research.

Courtney Sill, Coriell Institute for Medical Research

View Media

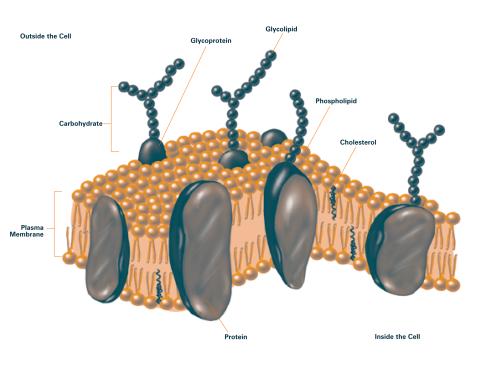

2524: Plasma membrane (with labels)

2524: Plasma membrane (with labels)

The plasma membrane is a cell's protective barrier. See image 2523 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The Chemistry of Health.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2744: Dynamin structure

2744: Dynamin structure

When a molecule arrives at a cell's outer membrane, the membrane creates a pouch around the molecule that protrudes inward. Directed by a protein called dynamin, the pouch then gets pinched off to form a vesicle that carries the molecule to the right place inside the cell. To better understand how dynamin performs its vital pouch-pinching role, researchers determined its structure. Based on the structure, they proposed that a dynamin "collar" at the pouch's base twists ever tighter until the vesicle pops free. Because cells absorb many drugs through vesicles, the discovery could lead to new drug delivery methods.

Josh Chappie, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH

View Media

1244: Nerve ending

1244: Nerve ending

A scanning electron microscope picture of a nerve ending. It has been broken open to reveal vesicles (orange and blue) containing chemicals used to pass messages in the nervous system.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

These cells are induced stem cells made from human adult skin cells that were genetically reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. The induced stem cells were made potentially safer by removing the introduced genes and the viral vector used to ferry genes into the cells, a loop of DNA called a plasmid. The work was accomplished by geneticist Junying Yu in the laboratory of James Thomson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor and the director of regenerative biology for the Morgridge Institute for Research.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

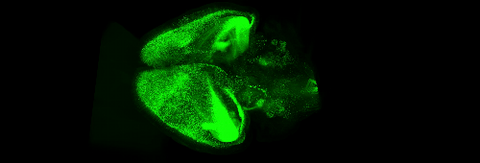

6931: Mouse brain 3

6931: Mouse brain 3

Various views of a mouse brain that was genetically modified so that subpopulations of its neurons glow. Researchers often study mice because they share many genes with people and can shed light on biological processes, development, and diseases in humans.

This video was captured using a light sheet microscope.

Related to images 6929 and 6930.

This video was captured using a light sheet microscope.

Related to images 6929 and 6930.

Prayag Murawala, MDI Biological Laboratory and Hannover Medical School.

View Media

1089: Natcher Building 09

1089: Natcher Building 09

NIGMS staff are located in the Natcher Building on the NIH campus.

Alisa Machalek, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

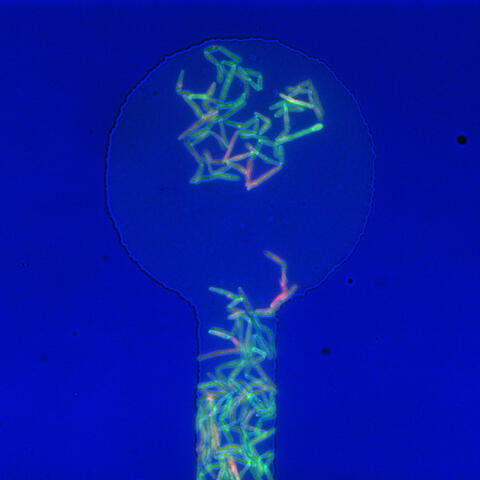

5751: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 1

5751: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 1

Antibiotic resistance in microbes is a serious health concern. So researchers have turned their attention to how bacteria undo the action of some antibiotics. Here, scientists set out to find the conditions that help individual bacterial cells survive in the presence of the antibiotic rifampicin. The research team used Mycobacterium smegmatis, a more harmless relative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which infects the lung and other organs and causes serious disease.

In this image, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to video 5752.

In this image, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to video 5752.

Bree Aldridge, Tufts University

View Media

2709: Retroviruses as fossils

2709: Retroviruses as fossils

DNA doesn't leave a fossil record in stone, the way bones do. Instead, the DNA code itself holds the best evidence for organisms' genetic history. Some of the most telling evidence about genetic history comes from retroviruses, the remnants of ancient viral infections.

Emily Harrington, science illustrator

View Media

2397: Bovine milk alpha-lactalbumin (1)

2397: Bovine milk alpha-lactalbumin (1)

A crystal of bovine milk alpha-lactalbumin protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

3550: Protein clumping in zinc-deficient yeast cells

3550: Protein clumping in zinc-deficient yeast cells

The green spots in this image are clumps of protein inside yeast cells that are deficient in both zinc and a protein called Tsa1 that prevents clumping. Protein clumping plays a role in many diseases, including Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, where proteins clump together in the brain. Zinc deficiency within a cell can cause proteins to mis-fold and eventually clump together. Normally, in yeast, Tsa1 codes for so-called "chaperone proteins" which help proteins in stressed cells, such as those with a zinc deficiency, fold correctly. The research behind this image was published in 2013 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Colin MacDiarmid and David Eide, University of Wisconsin--Madison

View Media

2603: Induced stem cells from adult skin 01

2603: Induced stem cells from adult skin 01

These cells are induced stem cells made from human adult skin cells that were genetically reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. The induced stem cells were made potentially safer by removing the introduced genes and the viral vector used to ferry genes into the cells, a loop of DNA called a plasmid. The work was accomplished by geneticist Junying Yu in the laboratory of James Thomson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor and the director of regenerative biology for the Morgridge Institute for Research.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

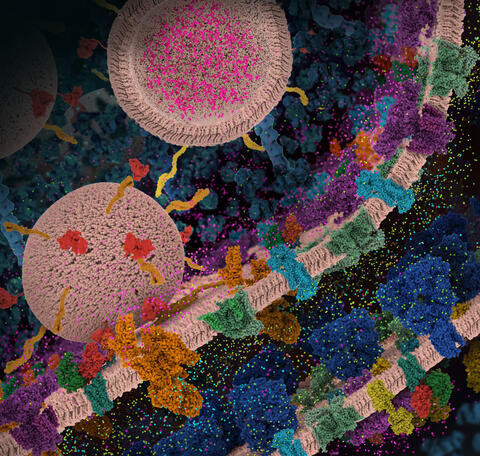

6992: Molecular view of glutamatergic synapse

6992: Molecular view of glutamatergic synapse

This illustration highlights spherical pre-synaptic vesicles that carry the neurotransmitter glutamate. The presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes are shown with proteins relevant for transmitting and modulating the neuronal signal.

PDB 101’s Opioids and Pain Signaling video explains how glutamatergic synapses are involved in the process of pain signaling.

PDB 101’s Opioids and Pain Signaling video explains how glutamatergic synapses are involved in the process of pain signaling.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

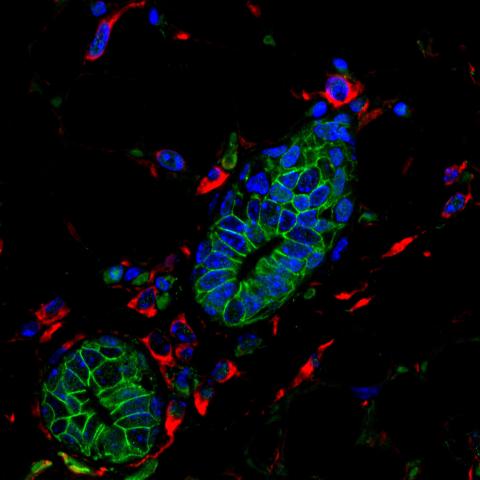

3432: Mouse mammary cells lacking anti-cancer protein

3432: Mouse mammary cells lacking anti-cancer protein

Shortly after a pregnant woman gives birth, her breasts start to secrete milk. This process is triggered by hormonal and genetic cues, including the protein Elf5. Scientists discovered that Elf5 also has another job--it staves off cancer. Early in the development of breast cancer, human breast cells often lose Elf5 proteins. Cells without Elf5 change shape and spread readily--properties associated with metastasis. This image shows cells in the mouse mammary gland that are lacking Elf5, leading to the overproduction of other proteins (red) that increase the likelihood of metastasis.

Nature Cell Biology, November 2012, Volume 14 No 11 pp1113-1231

View Media

2304: Bacteria working to eat

2304: Bacteria working to eat

Gram-negative bacteria perform molecular acrobatics just to eat. Because they're encased by two membranes, they must haul nutrients across both. To test one theory of how the bacteria manage this feat, researchers used computer simulations of two proteins involved in importing vitamin B12. Here, the protein (red) anchored in the inner membrane of bacteria tugs on a much larger protein (green and blue) in the outer membrane. Part of the larger protein unwinds, creating a pore through which the vitamin can pass.

Emad Tajkhorshid, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

View Media

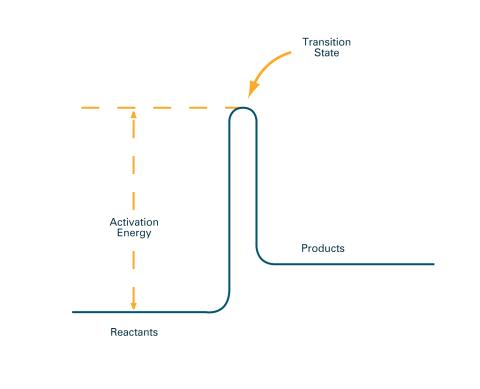

2526: Activation energy (with labels)

2526: Activation energy (with labels)

To become products, reactants must overcome an energy hill. See image 2525 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The Chemistry of Health.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

6602: See how immune cell acid destroys bacterial proteins

6602: See how immune cell acid destroys bacterial proteins

This animation shows the effect of exposure to hypochlorous acid, which is found in certain types of immune cells, on bacterial proteins. The proteins unfold and stick to one another, leading to cell death.

American Chemistry Council

View Media

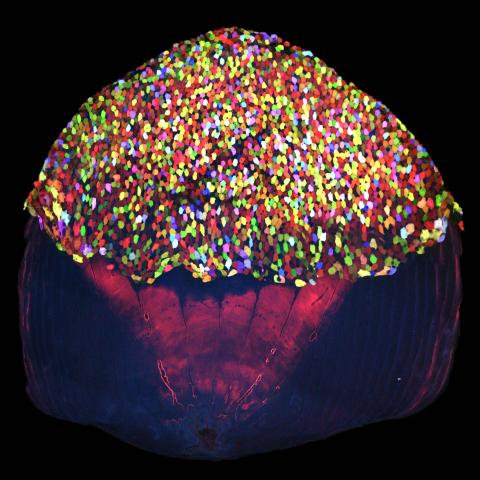

3783: A multicolored fish scale 2

3783: A multicolored fish scale 2

Each of the tiny colored specs in this image is a cell on the surface of a fish scale. To better understand how wounds heal, scientists have inserted genes that make cells brightly glow in different colors into the skin cells of zebrafish, a fish often used in laboratory research. The colors enable the researchers to track each individual cell, for example, as it moves to the location of a cut or scrape over the course of several days. These technicolor fish endowed with glowing skin cells dubbed "skinbow" provide important insight into how tissues recover and regenerate after an injury.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3782.

For more information on skinbow fish, see the Biomedical Beat blog post Visualizing Skin Regeneration in Real Time and a press release from Duke University highlighting this research. Related to image 3782.

Chen-Hui Chen and Kenneth Poss, Duke University

View Media

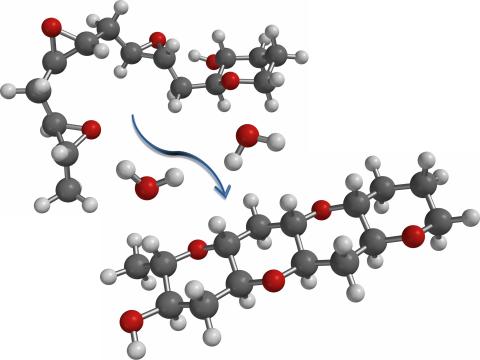

2490: Cascade reaction promoted by water

2490: Cascade reaction promoted by water

This illustration of an epoxide-opening cascade promoted by water emulates the proposed biosynthesis of some of the Red Tide toxins.

Tim Jamison, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

View Media

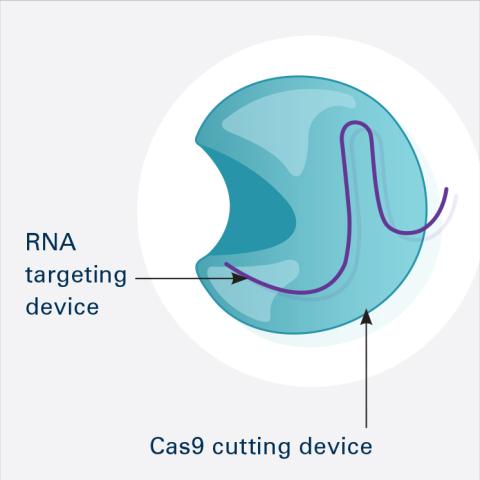

6465: CRISPR Illustration Frame 1

6465: CRISPR Illustration Frame 1

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool. This is the first frame in a series of four. The CRISPR system has two components joined together: a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence) and a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA).

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

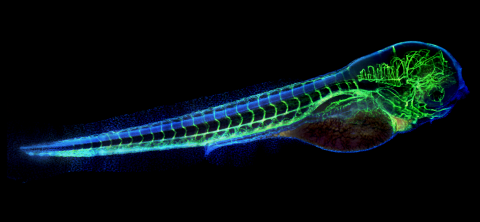

6661: Zebrafish embryo showing vasculature

6661: Zebrafish embryo showing vasculature

A zebrafish embryo. The blue areas are cell bodies, the green lines are blood vessels, and the red glow is blood. This image was created by stitching together five individual images captured with a hyperspectral multipoint confocal fluorescence microscope that was developed at the Eliceiri Lab.

Kevin Eliceiri, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

View Media

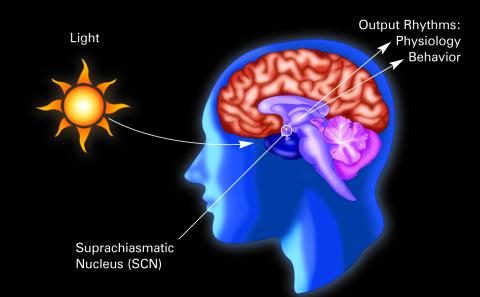

2569: Circadian rhythm (with labels)

2569: Circadian rhythm (with labels)

The human body keeps time with a master clock called the suprachiasmatic nucleus or SCN. Situated inside the brain, it's a tiny sliver of tissue about the size of a grain of rice, located behind the eyes. It sits quite close to the optic nerve, which controls vision, and this means that the SCN "clock" can keep track of day and night. The SCN helps control sleep and maintains our circadian rhythm--the regular, 24-hour (or so) cycle of ups and downs in our bodily processes such as hormone levels, blood pressure, and sleepiness. The SCN regulates our circadian rhythm by coordinating the actions of billions of miniature "clocks" throughout the body. These aren't actually clocks, but rather are ensembles of genes inside clusters of cells that switch on and off in a regular, 24-hour (or so) cycle in our physiological day.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2380: PanB from M. tuberculosis (1)

2380: PanB from M. tuberculosis (1)

Model of an enzyme, PanB, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes most cases of tuberculosis. This enzyme is an attractive drug target.

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Center, PSI

View Media

6772: Yeast cells responding to a glucose shortage

6772: Yeast cells responding to a glucose shortage

These yeast cells were exposed to a glucose (sugar) shortage. This caused the cells to compartmentalize HMGCR (green)—an enzyme involved in making cholesterol—to a patch on the nuclear envelope next to the vacuole/lysosome (purple). This process enhanced HMGCR activity and helped the yeast adapt to the glucose shortage. Researchers hope that understanding how yeast regulate cholesterol could ultimately lead to new ways to treat high cholesterol in people. This image was captured using a fluorescence microscope.

Mike Henne, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

View Media

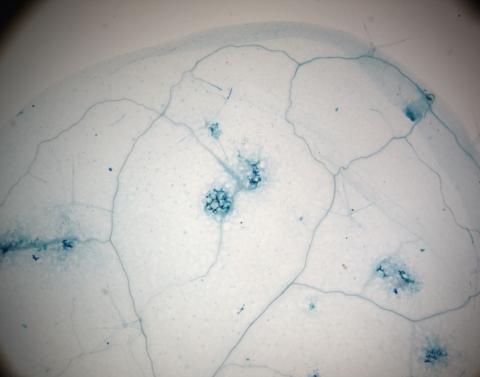

2781: Disease-resistant Arabidopsis leaf

2781: Disease-resistant Arabidopsis leaf

This is a magnified view of an Arabidopsis thaliana leaf a few days after being exposed to the pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. The plant from which this leaf was taken is genetically resistant to the pathogen. The spots in blue show areas of localized cell death where infection occurred, but it did not spread. Compare this response to that shown in Image 2782. Jeff Dangl has been funded by NIGMS to study the interactions between pathogens and hosts that allow or suppress infection.

Jeff Dangl, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

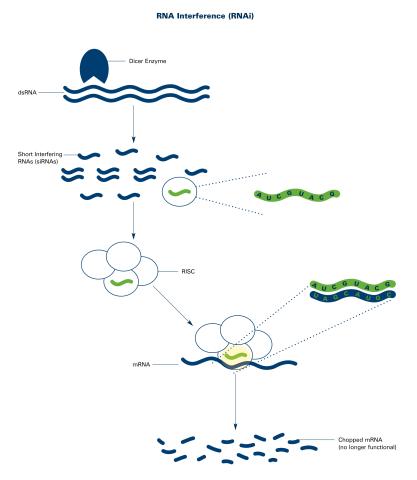

2559: RNA interference (with labels)

2559: RNA interference (with labels)

RNA interference or RNAi is a gene-silencing process in which double-stranded RNAs trigger the destruction of specific RNAs. See 2558 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

3746: Serum albumin structure 3

3746: Serum albumin structure 3

Serum albumin (SA) is the most abundant protein in the blood plasma of mammals. SA has a characteristic heart-shape structure and is a highly versatile protein. It helps maintain normal water levels in our tissues and carries almost half of all calcium ions in human blood. SA also transports some hormones, nutrients and metals throughout the bloodstream. Despite being very similar to our own SA, those from other animals can cause some mild allergies in people. Therefore, some scientists study SAs from humans and other mammals to learn more about what subtle structural or other differences cause immune responses in the body.

Related to entries 3744 and 3745.

Related to entries 3744 and 3745.

Wladek Minor, University of Virginia

View Media

2702: Thermotoga maritima and its metabolic network

2702: Thermotoga maritima and its metabolic network

A combination of protein structures determined experimentally and computationally shows us the complete metabolic network of a heat-loving bacterium.

View Media

1335: Telomerase illustration

1335: Telomerase illustration

Reactivating telomerase in our cells does not appear to be a good way to extend the human lifespan. Cancer cells reactivate telomerase.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

2495: VDAC-1 (4)

2495: VDAC-1 (4)

The structure of the pore-forming protein VDAC-1 from humans. This molecule mediates the flow of products needed for metabolism--in particular the export of ATP--across the outer membrane of mitochondria, the power plants for eukaryotic cells. VDAC-1 is involved in metabolism and the self-destruction of cells--two biological processes central to health.

Related to images 2491, 2494, and 2488.

Related to images 2491, 2494, and 2488.

Gerhard Wagner, Harvard Medical School

View Media

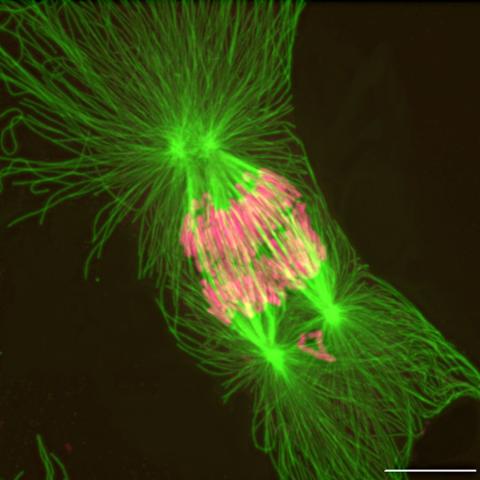

2739: Tetrapolar mitosis

2739: Tetrapolar mitosis

This image shows an abnormal, tetrapolar mitosis. Chromosomes are highlighted pink. The cells shown are S3 tissue cultured cells from Xenopus laevis, African clawed frog.

Gary Gorbsky, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation

View Media