Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

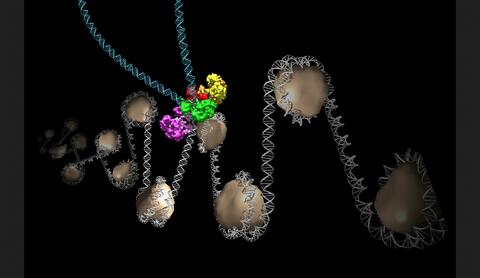

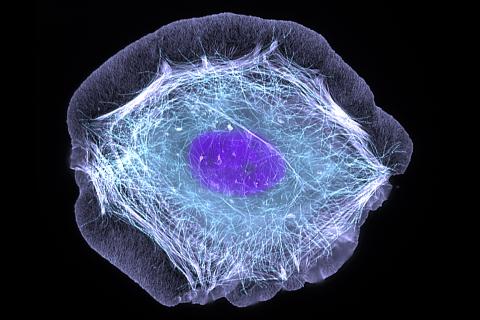

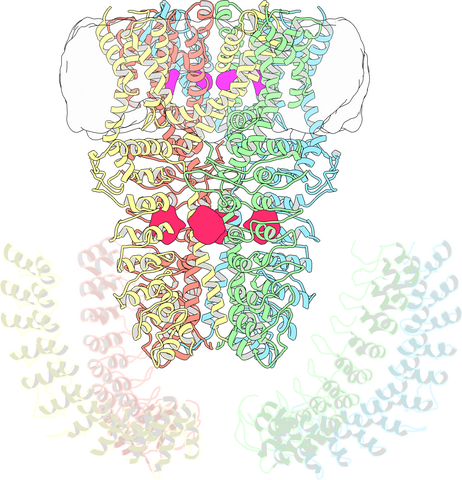

6346: Intasome

6346: Intasome

Salk researchers captured the structure of a protein complex called an intasome (center) that lets viruses similar to HIV establish permanent infection in their hosts. The intasome hijacks host genomic material, DNA (white) and histones (beige), and irreversibly inserts viral DNA (blue). The image was created by Jamie Simon and Dmitry Lyumkis. Work that led to the 3D map was published in: Ballandras-Colas A, Brown M, Cook NJ, Dewdney TG, Demeler B, Cherepanov P, Lyumkis D, & Engelman AN. (2016). Cryo-EM reveals a novel octameric integrase structure for ?-retroviral intasome function. Nature, 530(7590), 358—361

National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy http://nramm.nysbc.org/nramm-images/ Source: Bridget Carragher

View Media

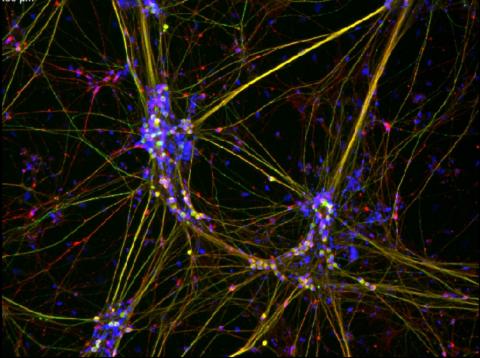

3263: Peripheral nerve cells derived from ES cells

3263: Peripheral nerve cells derived from ES cells

Peripheral nerve cells made from human embryonic stem cell-derived neural crest stem cells. The nuclei are shown in blue, and nerve cell proteins peripherin and beta-tubulin (Tuj1) are shown in green and red, respectively. Related to image 3264. Image is featured in October 2015 Biomedical Beat blog post Cool Images: A Halloween-Inspired Cell Collection.

Stephen Dalton, University of Georgia

View Media

1336: Life in balance

1336: Life in balance

Mitosis creates cells, and apoptosis kills them. The processes often work together to keep us healthy.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

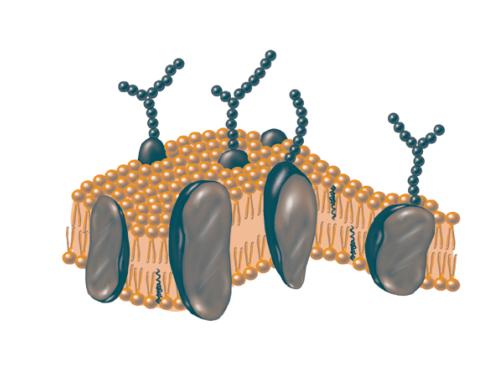

2523: Plasma membrane

2523: Plasma membrane

The plasma membrane is a cell's protective barrier. See image 2524 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The Chemistry of Health.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

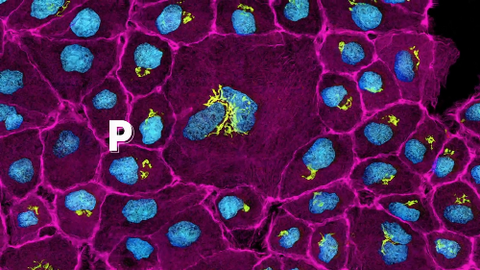

6538: Pathways: The Fascinating Cells of Research Organisms

6538: Pathways: The Fascinating Cells of Research Organisms

Learn how research organisms, such as fruit flies and mice, can help us understand and treat human diseases. Discover more resources from NIGMS’ Pathways collaboration with Scholastic. View the video on YouTube for closed captioning.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

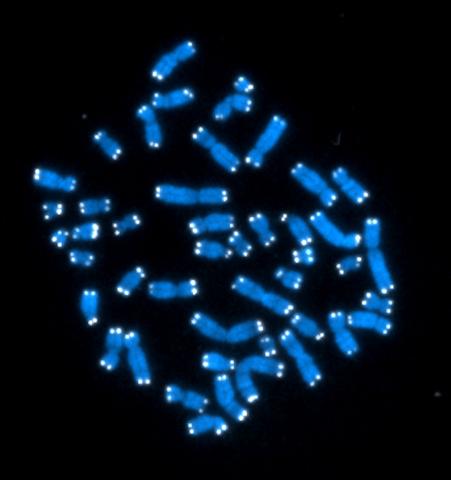

2626: Telomeres

2626: Telomeres

The 46 human chromosomes are shown in blue, with the telomeres appearing as white pinpoints. The DNA has already been copied, so each chromosome is actually made up of two identical lengths of DNA, each with its own two telomeres.

Hesed Padilla-Nash and Thomas Ried, the National Cancer Institute, a part of NIH

View Media

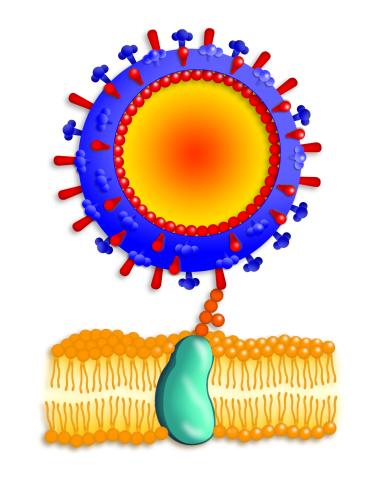

2425: Influenza virus attaches to host membrane

2425: Influenza virus attaches to host membrane

Influenza A infects a host cell when hemagglutinin grips onto glycans on its surface. Neuraminidase, an enzyme that chews sugars, helps newly made virus particles detach so they can infect other cells. Related to 213. Featured in the March 2006, issue of Findings in "Viral Voyages."

Crabtree + Company

View Media

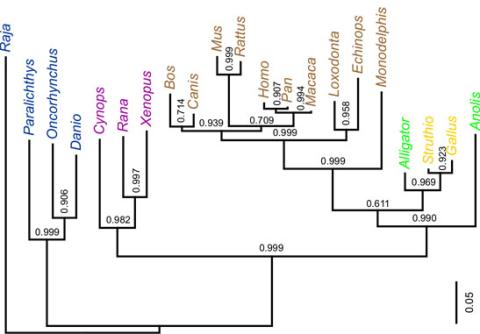

2474: Dinosaur evolutionary tree

2474: Dinosaur evolutionary tree

Analysis of 68 million-year-old collagen molecule fragments preserved in a T. rex femur confirmed what paleontologists have said for decades: Dinosaurs are close relatives of chickens, ostriches, and to a lesser extent, alligators. A Harvard University research team, including NIGMS-supported postdoctoral research fellow Chris Organ, used sophisticated statistical and computational tools to compare the ancient protein to ones from 21 living species. Because evolutionary processes produce similarities across species, the methods and results may help illuminate other areas of the evolutionary tree. Featured in the May 21, 2008 Biomedical Beat.

Chris Organ, Harvard University

View Media

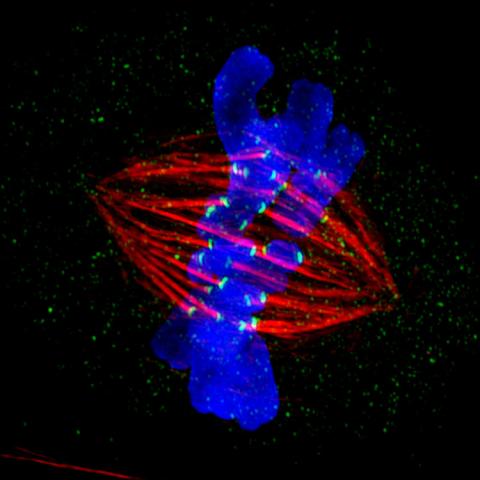

3445: Dividing cell in metaphase

3445: Dividing cell in metaphase

This image of a mammalian epithelial cell, captured in metaphase, was the winning image in the high- and super-resolution microscopy category of the 2012 GE Healthcare Life Sciences Cell Imaging Competition. The image shows microtubules (red), kinetochores (green) and DNA (blue). The DNA is fixed in the process of being moved along the microtubules that form the structure of the spindle.

The image was taken using the DeltaVision OMX imaging system, affectionately known as the "OMG" microscope, and was displayed on the NBC screen in New York's Times Square during the weekend of April 20-21, 2013. It was also part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

The image was taken using the DeltaVision OMX imaging system, affectionately known as the "OMG" microscope, and was displayed on the NBC screen in New York's Times Square during the weekend of April 20-21, 2013. It was also part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Jane Stout in the laboratory of Claire Walczak, Indiana University, GE Healthcare 2012 Cell Imaging Competition

View Media

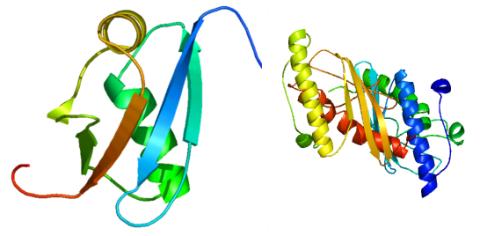

2388: Ubiquitin-fold modifier 1 from C. elegans

2388: Ubiquitin-fold modifier 1 from C. elegans

Solution NMR structure of protein target WR41 (left) from C. elegans. Noting the unanticipated structural similarity to the ubiquitin protein (Ub) found in all eukaryotic cells, researchers discovered that WR41 is a Ub-like modifier, ubiquitin-fold modifier 1 (Ufm1), on a newly uncovered ubiquitin-like pathway. Subsequently, the PSI group also determined the three-dimensional structure of protein target HR41 (right) from humans, the E2 ligase for Ufm1, using both NMR and X-ray crystallography.

Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium

View Media

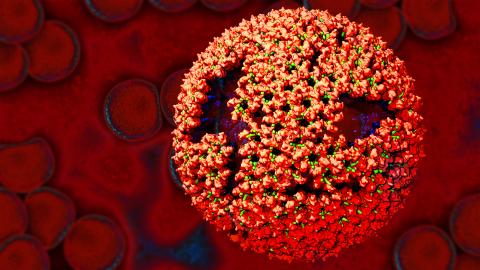

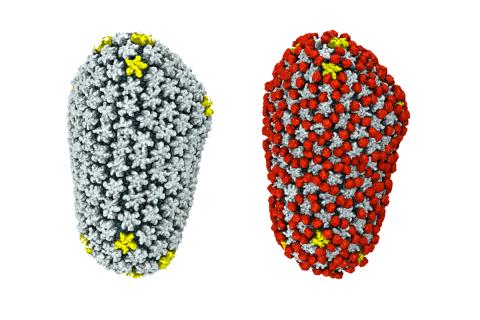

3771: Molecular model of freshly made Rous sarcoma virus (RSV)

3771: Molecular model of freshly made Rous sarcoma virus (RSV)

Viruses have been the foes of animals and other organisms for time immemorial. For almost as long, they've stayed well hidden from view because they are so tiny (they aren't even cells, so scientists call the individual virus a "particle"). This image shows a molecular model of a particle of the Rous sarcoma virus (RSV), a virus that infects and sometimes causes cancer in chickens. In the background is a photo of red blood cells. The particle shown is "immature" (not yet capable of infecting new cells) because it has just budded from an infected chicken cell and entered the bird's bloodstream. The outer shell of the immature virus is made up of a regular assembly of large proteins (shown in red) that are linked together with short protein molecules called peptides (green). This outer shell covers and protects the proteins (blue) that form the inner shell of the particle. But as you can see, the protective armor of the immature virus contains gaping holes. As the particle matures, the short peptides are removed and the large proteins rearrange, fusing together into a solid sphere capable of infecting new cells. While still immature, the particle is vulnerable to drugs that block its development. Knowing the structure of the immature particle may help scientists develop better medications against RSV and similar viruses in humans. Scientists used sophisticated computational tools to reconstruct the RSV atomic structure by crunching various data on the RSV proteins to simulate the entire structure of immature RSV.

Boon Chong Goh, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

View Media

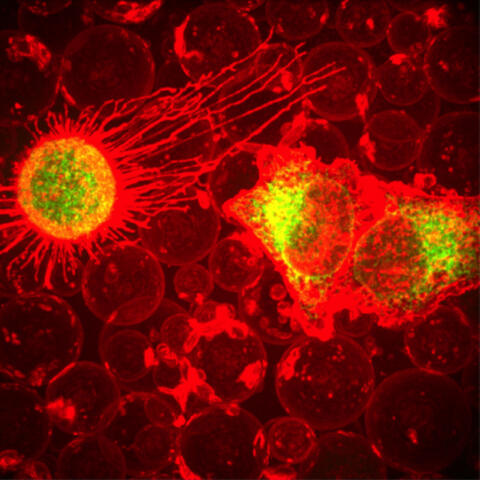

5887: Plasma-Derived Membrane Vesicles

5887: Plasma-Derived Membrane Vesicles

This fiery image doesn’t come from inside a bubbling volcano. Instead, it shows animal cells caught in the act of making bubbles, or blebbing. Some cells regularly pinch off parts of their membranes to produce bubbles filled with a mix of proteins and fats. The bubbles (red) are called plasma-derived membrane vesicles, or PMVs, and can travel to other parts of the body where they may aid in cell-cell communication. The University of Texas, Austin, researchers responsible for this photo are exploring ways to use PMVs to deliver medicines to precise locations in the body.

This image, entered in the Biophysical Society’s 2017 Art of Science Image contest, used two-channel spinning disk confocal fluorescence microscopy. It was also featured in the NIH Director’s Blog in May 2017.

This image, entered in the Biophysical Society’s 2017 Art of Science Image contest, used two-channel spinning disk confocal fluorescence microscopy. It was also featured in the NIH Director’s Blog in May 2017.

Jeanne Stachowiak, University of Texas at Austin

View Media

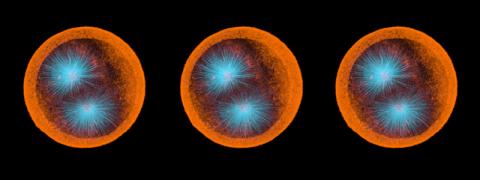

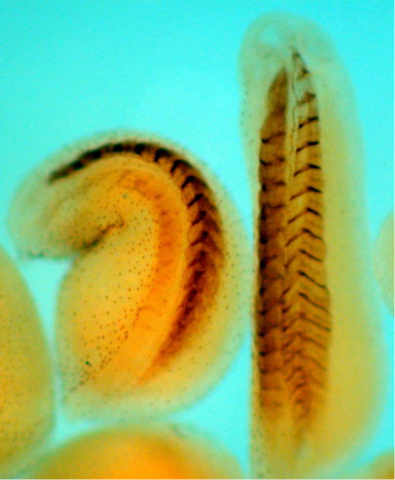

2756: Xenopus laevis embryos

2756: Xenopus laevis embryos

Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog, has long been used as a model organism for studying embryonic development. The frog embryo on the left lacks the developmental factor Sizzled. A normal embryo is shown on the right.

Michael Klymkowsky, University of Colorado, Boulder

View Media

5766: A chromosome goes missing in anaphase

5766: A chromosome goes missing in anaphase

Anaphase is the critical step during mitosis when sister chromosomes are disjoined and directed to opposite spindle poles, ensuring equal distribution of the genome during cell division. In this image, one pair of sister chromosomes at the top was lost and failed to divide after chemical inhibition of polo-like kinase 1. This image depicts chromosomes (blue) separating away from the spindle mid-zone (red). Kinetochores (green) highlight impaired movement of some chromosomes away from the mid-zone or the failure of sister chromatid separation (top). Scientists are interested in detailing the signaling events that are disrupted to produce this effect. The image is a volume projection of multiple deconvolved z-planes acquired with a Nikon widefield fluorescence microscope.

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call. The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

Related to image 5765.

View Media

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call. The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

Related to image 5765.

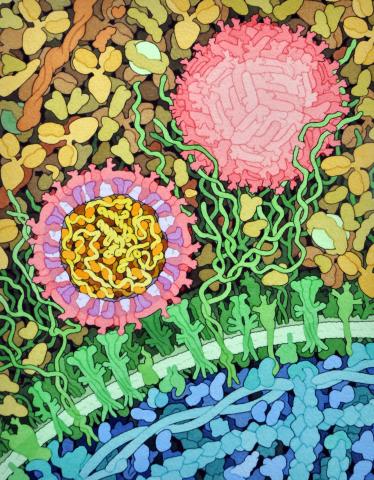

6998: Zika virus

6998: Zika virus

Zika virus is shown in cross section at center left. On the outside, it includes envelope protein (red) and membrane protein (magenta) embedded in a lipid membrane (light purple). Inside, the RNA genome (yellow) is associated with capsid proteins (orange). The viruses are shown interacting with receptors on the cell surface (green) and are surrounded by blood plasma molecules at the top.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

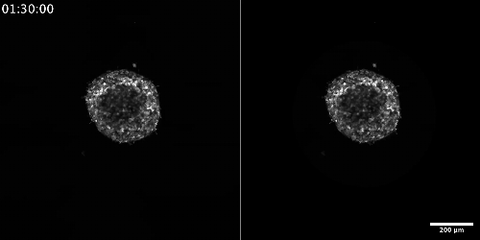

6986: Breast cancer cells change migration phenotypes

6986: Breast cancer cells change migration phenotypes

Cancer cells can change their migration phenotype, which includes their shape and the way that they move to invade different tissues. This movie shows breast cancer cells forming a tumor spheroid—a 3D ball of cancer cells—and invading the surrounding tissue. Images were taken using a laser scanning confocal microscope, and artificial intelligence (AI) models were used to segment and classify the images by migration phenotype. On the right side of the video, each phenotype is represented by a different color, as recognized by the AI program based on identifiable characteristics of those phenotypes. The movie demonstrates how cancer cells can use different migration modes during growth and metastasis—the spreading of cancer cells within the body.

Bo Sun, Oregon State University.

View Media

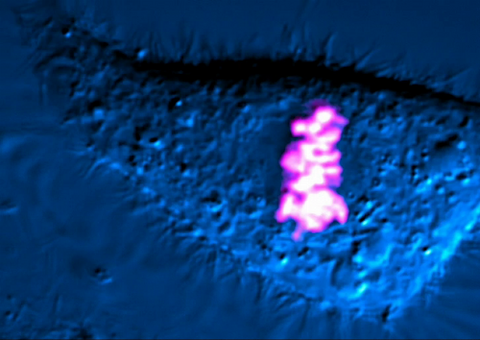

6965: Dividing cell

6965: Dividing cell

As this cell was undergoing cell division, it was imaged with two microscopy techniques: differential interference contrast (DIC) and confocal. The DIC view appears in blue and shows the entire cell. The confocal view appears in pink and shows the chromosomes.

Dylan T. Burnette, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

View Media

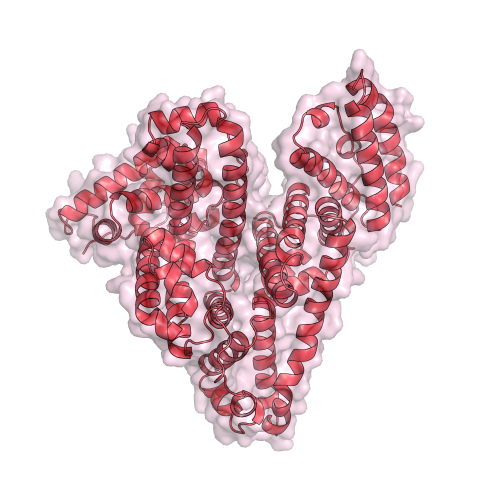

3744: Serum albumin structure 1

3744: Serum albumin structure 1

Serum albumin (SA) is the most abundant protein in the blood plasma of mammals. SA has a characteristic heart-shape structure and is a highly versatile protein. It helps maintain normal water levels in our tissues and carries almost half of all calcium ions in human blood. SA also transports some hormones, nutrients and metals throughout the bloodstream. Despite being very similar to our own SA, those from other animals can cause some mild allergies in people. Therefore, some scientists study SAs from humans and other mammals to learn more about what subtle structural or other differences cause immune responses in the body.

Related to entries 3745 and 3746.

Related to entries 3745 and 3746.

Wladek Minor, University of Virginia

View Media

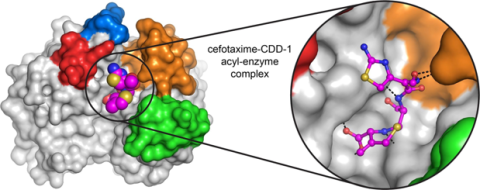

6767: Space-filling model of a cefotaxime-CCD-1 complex

6767: Space-filling model of a cefotaxime-CCD-1 complex

CCD-1 is an enzyme produced by the bacterium Clostridioides difficile that helps it resist antibiotics. Using X-ray crystallography, researchers determined the structure of a complex between CCD-1 and the antibiotic cefotaxime (purple, yellow, and blue molecule). The structure revealed that CCD-1 provides extensive hydrogen bonding (shown as dotted lines) and stabilization of the antibiotic in the active site, leading to efficient degradation of the antibiotic.

Related to images 6764, 6765, and 6766.

Related to images 6764, 6765, and 6766.

Keith Hodgson, Stanford University.

View Media

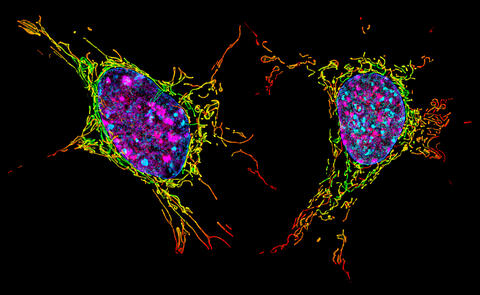

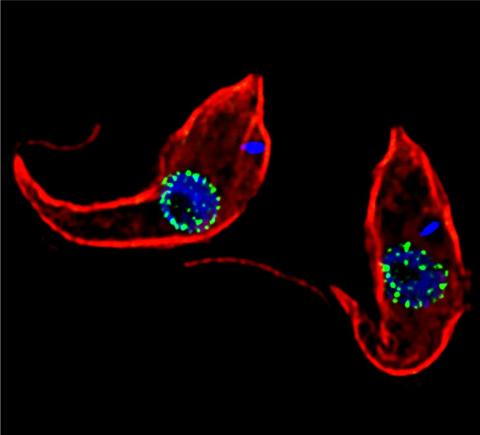

6789: Two mouse fibroblast cells

6789: Two mouse fibroblast cells

Two mouse fibroblasts, one of the most common types of cells in mammalian connective tissue. They play a key role in wound healing and tissue repair. This image was captured using structured illumination microscopy.

Dylan T. Burnette, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

View Media

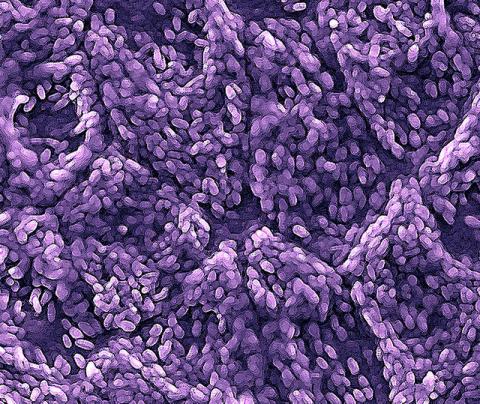

3286: Retinal pigment epithelium derived from human ES cells

3286: Retinal pigment epithelium derived from human ES cells

This color-enhanced image is a scanning electron microscope image of retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. The cells are remarkably similar to normal RPE cells, growing in a hexagonal shape in a single, well-defined layer. This kind of retinal cell is responsible for macular degeneration, the most common cause of blindness. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Related to image 3287.

David Hinton lab, University of Southern California, via CIRM

View Media

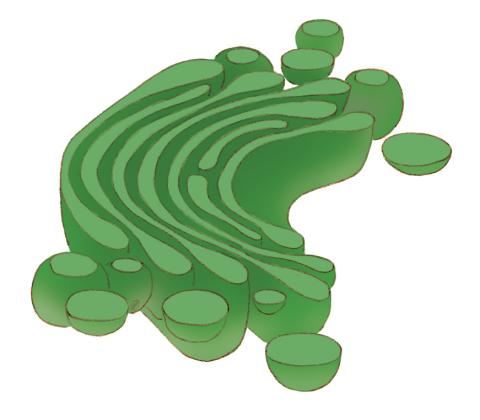

1275: Golgi

1275: Golgi

The Golgi complex, also called the Golgi apparatus or, simply, the Golgi. This organelle receives newly made proteins and lipids from the ER, puts the finishing touches on them, addresses them, and sends them to their final destinations.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

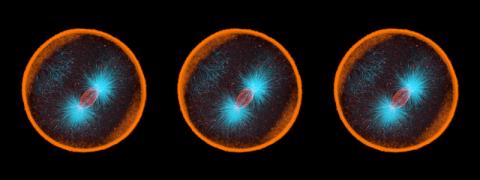

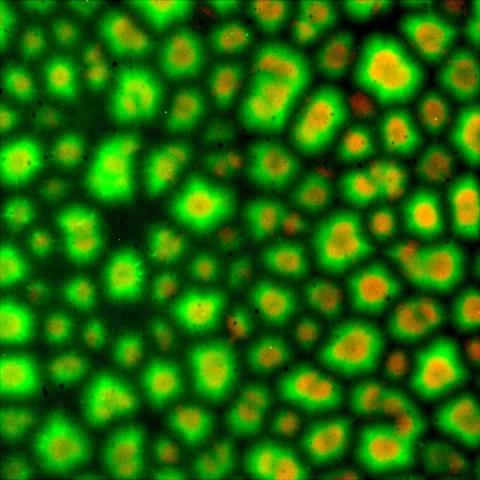

6586: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs 3

6586: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs 3

Cell-like compartments that spontaneously emerged from scrambled frog eggs. Endoplasmic reticulum (red) and microtubules (green) are visible. Image created using epifluorescence microscopy.

For more photos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6584, 6585, 6591, 6592, and 6593.

For videos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6587, 6588, 6589, and 6590.

Xianrui Cheng, Stanford University School of Medicine.

View Media

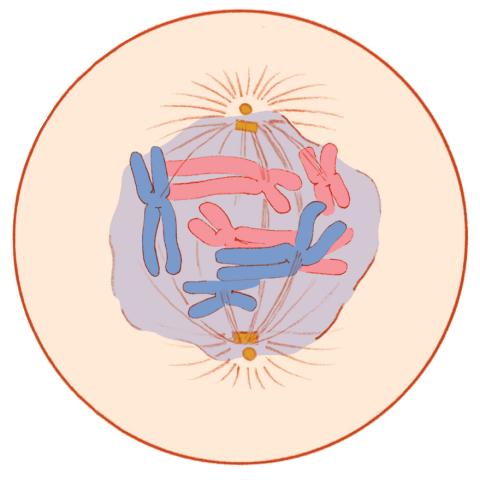

1331: Mitosis - prometaphase

1331: Mitosis - prometaphase

A cell in prometaphase during mitosis: The nuclear membrane breaks apart, and the spindle starts to interact with the chromosomes. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

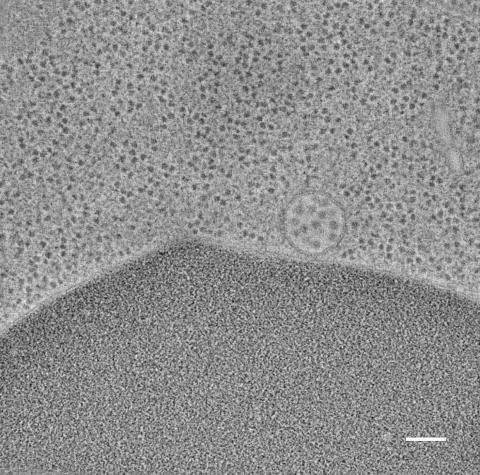

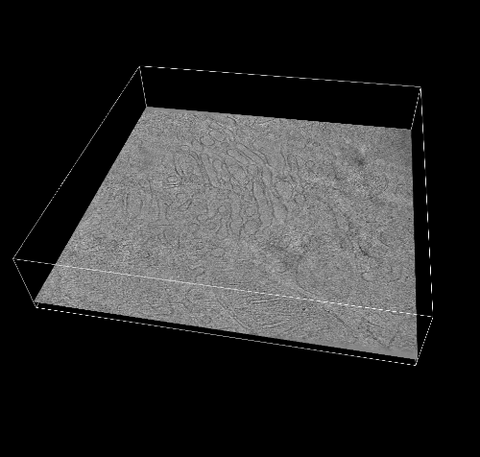

5768: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 2

5768: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 2

Collecting and transporting cellular waste and sorting it into recylable and nonrecylable pieces is a complex business in the cell. One key player in that process is the endosome, which helps collect, sort and transport worn-out or leftover proteins with the help of a protein assembly called the endosomal sorting complexes for transport (or ESCRT for short). These complexes help package proteins marked for breakdown into intralumenal vesicles, which, in turn, are enclosed in multivesicular bodies for transport to the places where the proteins are recycled or dumped. In this image, a multivesicular body (the round structure slightly to the right of center) contain tiny intralumenal vesicles (with a diameter of only 25 nanometers; the round specks inside the larger round structure) adjacent to the cell's vacuole (below the multivesicular body, shown in darker and more uniform gray).

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a color-enhanced version 5767 and image 5769.

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a color-enhanced version 5767 and image 5769.

Matthew West and Greg Odorizzi, University of Colorado

View Media

1120: Superconducting magnet

1120: Superconducting magnet

Superconducting magnet for NMR research, from the February 2003 profile of Dorothee Kern in Findings.

Mike Lovett

View Media

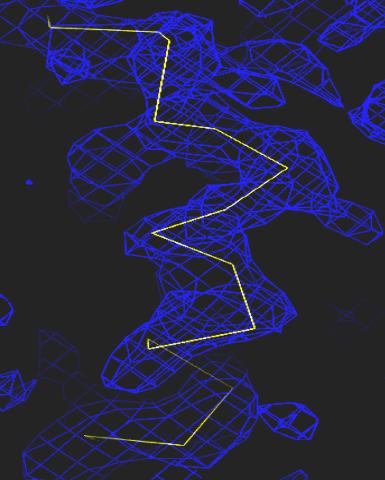

2354: Section of an electron density map

2354: Section of an electron density map

Electron density maps such as this one are generated from the diffraction patterns of X-rays passing through protein crystals. These maps are then used to generate a model of the protein's structure by fitting the protein's amino acid sequence (yellow) into the observed electron density (blue).

The Southeast Collaboratory for Structural Genomics

View Media

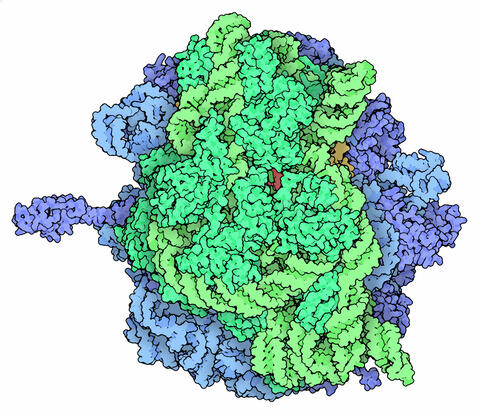

5780: Ribosome illustration from PDB

5780: Ribosome illustration from PDB

Ribosomes are complex machines made up of more than 50 proteins and three or four strands of genetic material called ribosomal RNA (rRNA). The busy cellular machines make proteins, which are critical to almost every structure and function in the cell. To do so, they read protein-building instructions, which come as strands of messenger RNA. Ribosomes are found in all forms of cellular life—people, plants, animals, even bacteria. This illustration of a bacterial ribosome was produced using detailed information about the position of every atom in the complex. Several antibiotic medicines work by disrupting bacterial ribosomes but leaving human ribosomes alone. Scientists are carefully comparing human and bacterial ribosomes to spot differences between the two. Structures that are present only in the bacterial version could serve as targets for new antibiotic medications.

From PDB’s Molecule of the Month collection (direct link: http://pdb101.rcsb.org/motm/121) Molecule of the Month illustrations are available under a CC-BY-4.0 license. Attribution should be given to David S. Goodsell and the RCSB PDB.

View Media

1081: Natcher Building 01

1081: Natcher Building 01

NIGMS staff are located in the Natcher Building on the NIH campus.

Alisa Machalek, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

3765: Trypanosoma brucei, the cause of sleeping sickness

3765: Trypanosoma brucei, the cause of sleeping sickness

Trypanosoma brucei is a single-cell parasite that causes sleeping sickness in humans. Scientists have been studying trypanosomes for some time because of their negative effects on human and also animal health, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, because these organisms evolved on a separate path from those of animals and plants more than a billion years ago, researchers study trypanosomes to find out what traits they may harbor that are common to or different from those of other eukaryotes (i.e., those organisms having a nucleus and mitochondria). This image shows the T. brucei cell membrane in red, the DNA in the nucleus and kinetoplast (a structure unique to protozoans, including trypanosomes, which contains mitochondrial DNA) in blue and nuclear pore complexes (which allow molecules to pass into or out of the nucleus) in green. Scientists have found that the trypanosome nuclear pore complex has a unique mechanism by which it attaches to the nuclear envelope. In addition, the trypanosome nuclear pore complex differs from those of other eukaryotes because its components have a near-complete symmetry, and it lacks almost all of the proteins that in other eukaryotes studied so far are required to assemble the pore.

Michael Rout, Rockefeller University

View Media

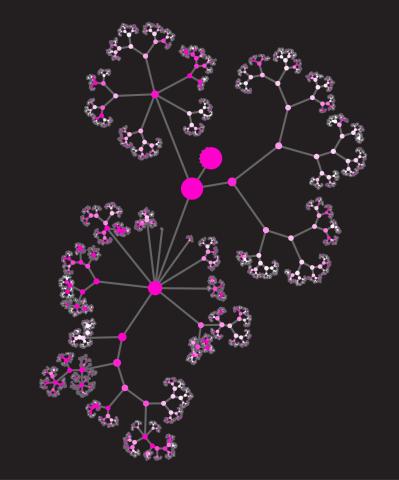

3436: Network diagram of genes, cellular components and processes (unlabeled)

3436: Network diagram of genes, cellular components and processes (unlabeled)

This image shows the hierarchical ontology of genes, cellular components and processes derived from large genomic datasets. From Dutkowski et al. A gene ontology inferred from molecular networks Nat Biotechnol. 2013 Jan;31(1):38-45. Related to 3437.

Janusz Dutkowski and Trey Ideker

View Media

7013: An adult Hawaiian bobtail squid

7013: An adult Hawaiian bobtail squid

An adult female Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, with its mantle cavity exposed from the underside. Some internal organs are visible, including the two lobes of the light organ that contains bioluminescent bacteria, Vibrio fischeri. The light organ includes accessory tissues like an ink sac (black) that serves as a shutter, and a silvery reflector that directs the light out of the underside of the animal.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

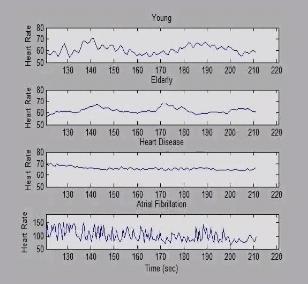

3596: Heart rates time series image

3596: Heart rates time series image

These time series show the heart rates of four different individuals. Automakers use steel scraps to build cars, construction companies repurpose tires to lay running tracks, and now scientists are reusing previously discarded medical data to better understand our complex physiology. Through a website called PhysioNet developed in part by Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center cardiologist Ary Goldberger, scientists can access complete physiologic recordings, such as heart rate, respiration, brain activity and gait. They then can use free software to analyze the data and find patterns in it. The patterns could ultimately help health care professionals diagnose and treat health conditions like congestive heart failure, sleeping disorders, epilepsy and walking problems. PhysioNet is supported by NIH's National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering as well as by NIGMS.

Madalena Costa and Ary Goldberger, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

View Media

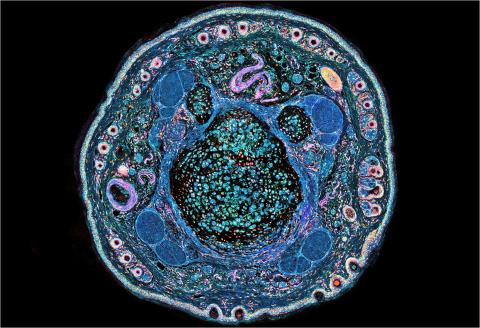

6609: 3D reconstruction of the Golgi apparatus in a pancreas cell

6609: 3D reconstruction of the Golgi apparatus in a pancreas cell

Researchers used cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) to capture images of a rat pancreas cell that were then compiled and color-coded to produce a 3D reconstruction. Visible features include the folded sacs of the Golgi apparatus (copper), transport vesicles (medium-sized dark-blue circles), microtubules (neon-green rods), a mitochondria membrane (pink), ribosomes (small pale-yellow circles), endoplasmic reticulum (aqua), and lysosomes (large yellowish-green circles). See 6606 for a still image from the video.

Xianjun Zhang, University of Southern California.

View Media

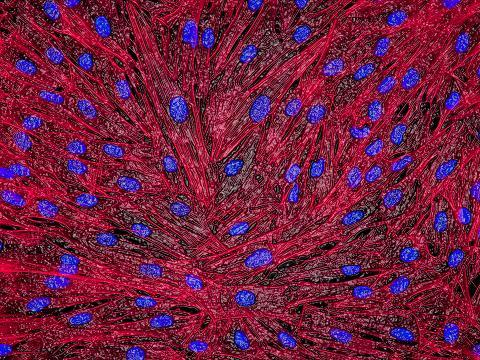

3670: DNA and actin in cultured fibroblast cells

3670: DNA and actin in cultured fibroblast cells

DNA (blue) and actin (red) in cultured fibroblast cells.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

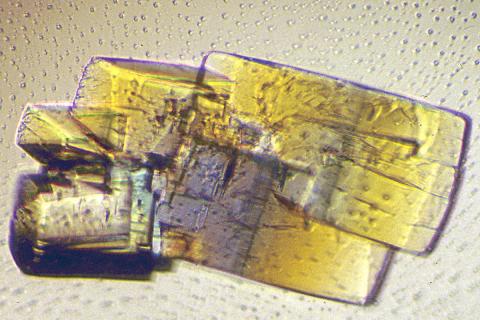

2402: RNase A (2)

2402: RNase A (2)

A crystal of RNase A protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

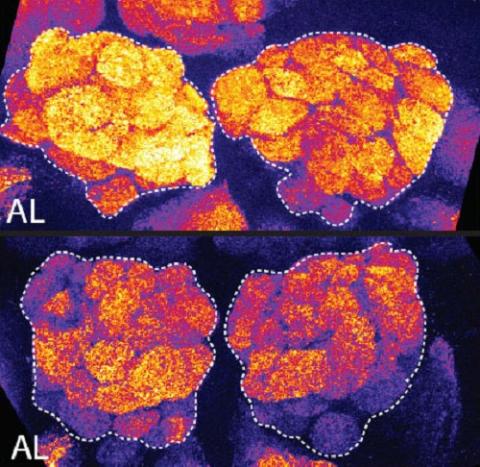

3490: Brains of sleep-deprived and well-rested fruit flies

3490: Brains of sleep-deprived and well-rested fruit flies

On top, the brain of a sleep-deprived fly glows orange because of Bruchpilot, a communication protein between brain cells. These bright orange brain areas are associated with learning. On the bottom, a well-rested fly shows lower levels of Bruchpilot, which might make the fly ready to learn after a good night's rest.

Chiara Cirelli, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

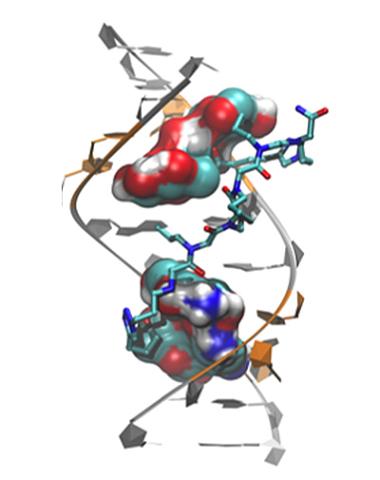

3573: Myotonic dystrophy type 2 genetic defect

3573: Myotonic dystrophy type 2 genetic defect

Scientists revealed a detailed image of the genetic defect that causes myotonic dystrophy type 2 and used that information to design drug candidates to counteract the disease.

Matthew Disney, Scripps Research Institute and Ilyas Yildirim, Northwestern University

View Media

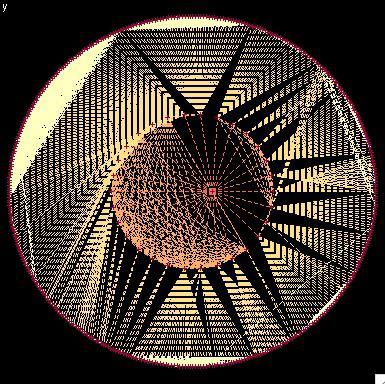

3755: Cryo-EM reveals how the HIV capsid attaches to a human protein to evade immune detection

3755: Cryo-EM reveals how the HIV capsid attaches to a human protein to evade immune detection

The illustration shows the capsid of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) whose molecular features were resolved with cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). On the left, the HIV capsid is "naked," a state in which it would be easily detected by and removed from cells. However, as shown on the right, when the viral capsid binds to and is covered with a host protein, called cyclophilin A (shown in red), it evades detection and enters and invades the human cell to use it to establish an infection. To learn more about how cyclophilin A helps HIV infect cells and how scientists used cryo-EM to find out the mechanism by which the HIV capsid attaches to cyclophilin A, see this news release by the University of Illinois. A study reporting these findings was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Juan R. Perilla, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

View Media

2322: Modeling disease spread

2322: Modeling disease spread

What looks like a Native American dream catcher is really a network of social interactions within a community. The red dots along the inner and outer circles represent people, while the different colored lines represent direct contact between them. All connections originate from four individuals near the center of the graph. Modeling social networks can help researchers understand how diseases spread.

Stephen Eubank, University of Virginia Biocomplexity Institute (formerly Virginia Bioinformatics Institute)

View Media

3395: NCMIR mouse tail

3395: NCMIR mouse tail

Stained cross section of a mouse tail.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

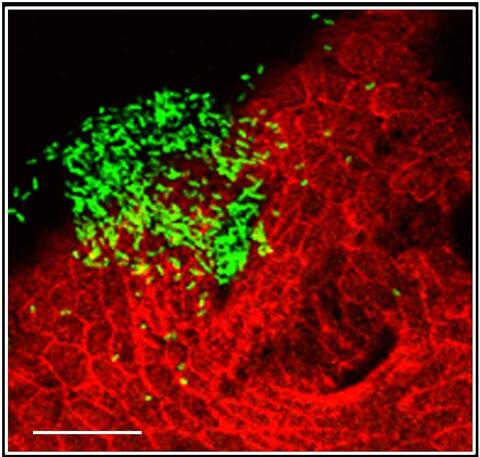

7019: Bacterial cells aggregated above a light-organ pore of the Hawaiian bobtail squid

7019: Bacterial cells aggregated above a light-organ pore of the Hawaiian bobtail squid

The beating of cilia on the outside of the Hawaiian bobtail squid’s light organ concentrates Vibrio fischeri cells (green) present in the seawater into aggregates near the pore-containing tissue (red). From there, the bacterial cells (~2 mm) swim to the pores and migrate through a bottleneck into the interior crypts where a population of symbionts grow and remain for the life of the host. This image was taken using confocal fluorescence microscopy.

Related to images 7016, 7017, 7018, and 7020.

Related to images 7016, 7017, 7018, and 7020.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

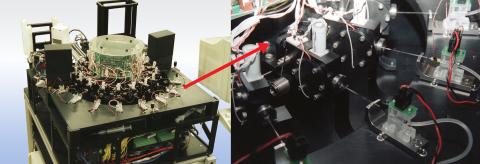

2357: Capillary protein crystallization robot

2357: Capillary protein crystallization robot

This ACAPELLA robot for capillary protein crystallization grows protein crystals, freezes them, and centers them without manual intervention. The close-up is a view of one of the dispensers used for dispensing proteins and reagents.

Structural Genomics of Pathogenic Protozoa Consortium

View Media

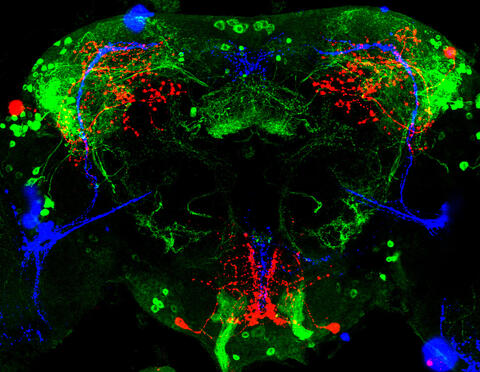

3754: Circadian rhythm neurons in the fruit fly brain

3754: Circadian rhythm neurons in the fruit fly brain

Some nerve cells (neurons) in the brain keep track of the daily cycle. This time-keeping mechanism, called the circadian clock, is found in all animals including us. The circadian clock controls our daily activities such as sleep and wakefulness. Researchers are interested in finding the neuron circuits involved in this time keeping and how the information about daily time in the brain is relayed to the rest of the body. In this image of a brain of the fruit fly Drosophila the time-of-day information flowing through the brain has been visualized by staining the neurons involved: clock neurons (shown in blue) function as "pacemakers" by communicating with neurons that produce a short protein called leucokinin (LK) (red), which, in turn, relays the time signal to other neurons, called LK-R neurons (green). This signaling cascade set in motion by the pacemaker neurons helps synchronize the fly's daily activity with the 24-hour cycle. To learn more about what scientists have found out about circadian pacemaker neurons in the fruit fly see this news release by New York University. This work was featured in the Biomedical Beat blog post Cool Image: A Circadian Circuit.

Justin Blau, New York University

View Media

3599: Skin cell (keratinocyte)

3599: Skin cell (keratinocyte)

This normal human skin cell was treated with a growth factor that triggered the formation of specialized protein structures that enable the cell to move. We depend on cell movement for such basic functions as wound healing and launching an immune response.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Torsten Wittmann, University of California, San Francisco

View Media

2724: Blinking bacteria

2724: Blinking bacteria

Like a pulsing blue shower, E. coli cells flash in synchrony. Genes inserted into each cell turn a fluorescent protein on and off at regular intervals. When enough cells grow in the colony, a phenomenon called quorum sensing allows them to switch from blinking independently to blinking in unison. Researchers can watch waves of light propagate across the colony. Adjusting the temperature, chemical composition or other conditions can change the frequency and amplitude of the waves. Because the blinks react to subtle changes in the environment, synchronized oscillators like this one could one day allow biologists to build cellular sensors that detect pollutants or help deliver drugs.

Jeff Hasty, University of California, San Diego

View Media

3747: Cryo-electron microscopy revealing the "wasabi receptor"

3747: Cryo-electron microscopy revealing the "wasabi receptor"

The TRPA1 protein is responsible for the burn you feel when you taste a bite of sushi topped with wasabi. Known therefore informally as the "wasabi receptor," this protein forms pores in the membranes of nerve cells that sense tastes or odors. Pungent chemicals like wasabi or mustard oil cause the pores to open, which then triggers a tingling or burn on our tongue. This receptor also produces feelings of pain in response to chemicals produced within our own bodies when our tissues are damaged or inflamed. Researchers used cryo-EM to reveal the structure of the wasabi receptor at a resolution of about 4 angstroms (a credit card is about 8 million angstroms thick). This detailed structure can help scientists understand both how we feel pain and how we can limit it by developing therapies to block the receptor. For more on cryo-EM see the blog post Cryo-Electron Microscopy Reveals Molecules in Ever Greater Detail.

Jean-Paul Armache, UCSF

View Media

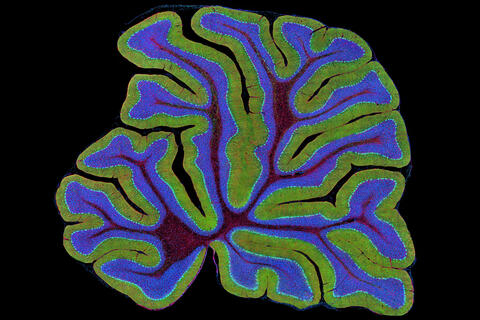

3639: Cerebellum: the brain's locomotion control center

3639: Cerebellum: the brain's locomotion control center

The cerebellum of a mouse is shown here in cross-section. The cerebellum is the brain's locomotion control center. Every time you shoot a basketball, tie your shoe or chop an onion, your cerebellum fires into action. Found at the base of your brain, the cerebellum is a single layer of tissue with deep folds like an accordion. People with damage to this region of the brain often have difficulty with balance, coordination and fine motor skills. For a higher magnification, see image 3371.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Thomas Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research, University of California, San Diego

View Media