Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

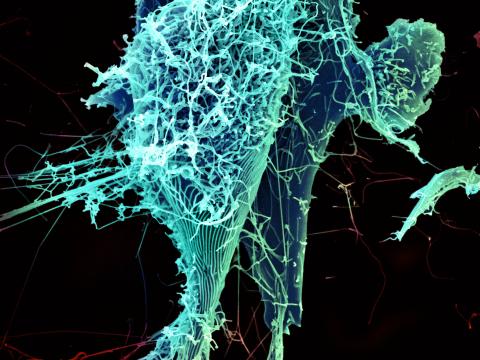

3619: String-like Ebola virus peeling off an infected cell

3619: String-like Ebola virus peeling off an infected cell

After multiplying inside a host cell, the stringlike Ebola virus is emerging to infect more cells. Ebola is a rare, often fatal disease that occurs primarily in tropical regions of sub-Saharan Africa. The virus is believed to spread to humans through contact with wild animals, especially fruit bats. It can be transmitted between one person and another through bodily fluids.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Heinz Feldmann, Peter Jahrling, Elizabeth Fischer and Anita Mora, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health

View Media

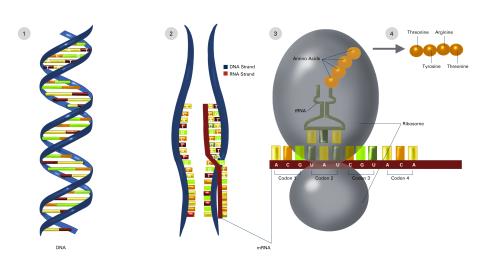

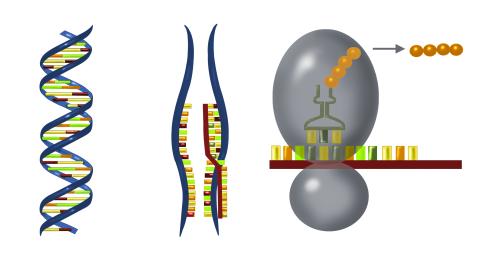

2549: Central dogma, illustrated (with labels and numbers for stages)

2549: Central dogma, illustrated (with labels and numbers for stages)

DNA encodes RNA, which encodes protein. DNA is transcribed to make messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA sequence (dark red strand) is complementary to the DNA sequence (blue strand). On ribosomes, transfer RNA (tRNA) reads three nucleotides at a time in mRNA to bring together the amino acids that link up to make a protein. See image 2548 for a version of this illustration that isn't numbered and 2547 for a an entirely unlabeled version. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

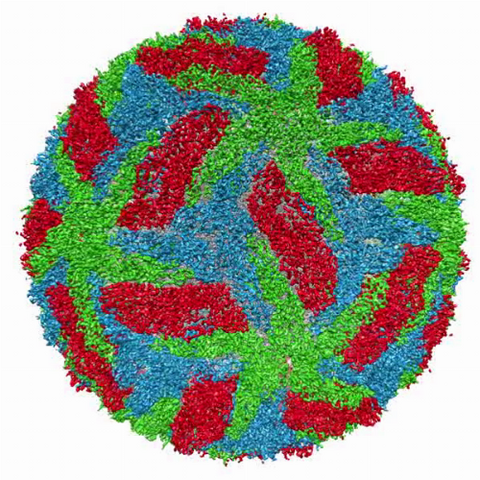

3748: Cryo-electron microscopy of the dengue virus showing protective membrane and membrane proteins

3748: Cryo-electron microscopy of the dengue virus showing protective membrane and membrane proteins

Dengue virus is a mosquito-borne illness that infects millions of people in the tropics and subtropics each year. Like many viruses, dengue is enclosed by a protective membrane. The proteins that span this membrane play an important role in the life cycle of the virus. Scientists used cryo-EM to determine the structure of a dengue virus at a 3.5-angstrom resolution to reveal how the membrane proteins undergo major structural changes as the virus matures and infects a host. For more on cryo-EM see the blog post Cryo-Electron Microscopy Reveals Molecules in Ever Greater Detail. Related to image 3756.

Hong Zhou, UCLA

View Media

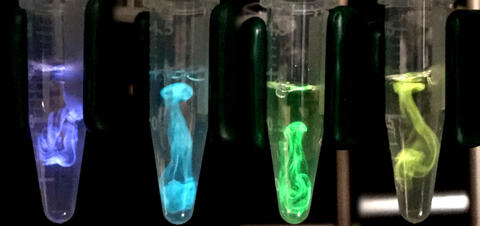

5895: Bioluminescence in a Tube

5895: Bioluminescence in a Tube

Details about the basic biology and chemistry of the ingredients that produce bioluminescence are allowing scientists to harness it as an imaging tool. Credit: Nathan Shaner, Scintillon Institute.

From Biomedical Beat article July 2017: Chasing Fireflies—and Better Cellular Imaging Techniques

From Biomedical Beat article July 2017: Chasing Fireflies—and Better Cellular Imaging Techniques

Nathan Shaner, Scintillon Institute

View Media

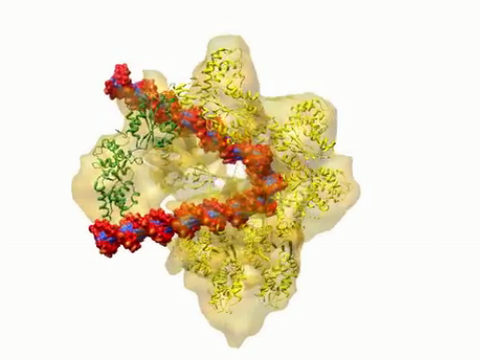

3307: DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC)

3307: DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC)

A study published in March 2012 used cryo-electron microscopy to determine the structure of the DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC), a semi-circular, protein complex (yellow) that recognizes and binds DNA to start the replication process. The ORC appears to wrap around and bend approximately 70 base pairs of double stranded DNA (red and blue). Also shown is the protein Cdc6 (green), which is also involved in the initiation of DNA replication. The video shows the structure from different angles. See related image 3597.

Huilin Li, Brookhaven National Laboratory

View Media

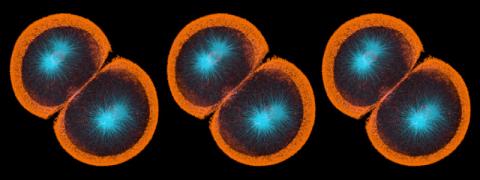

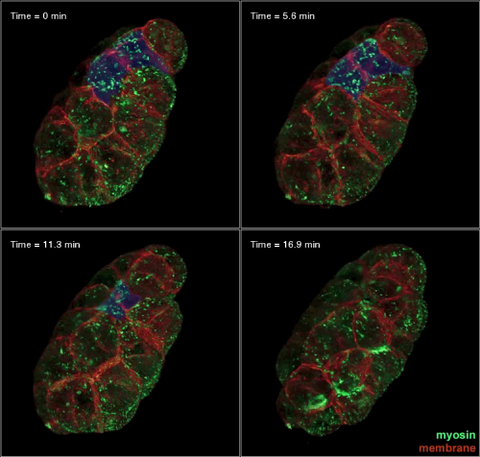

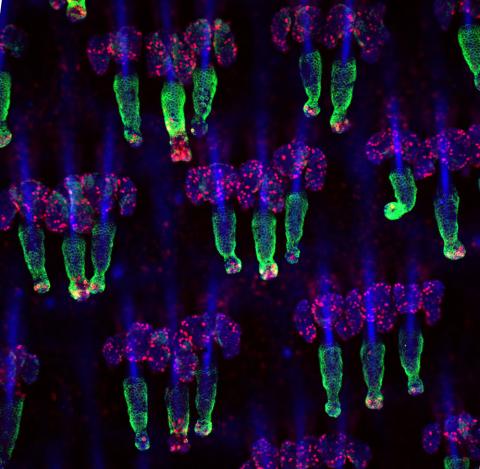

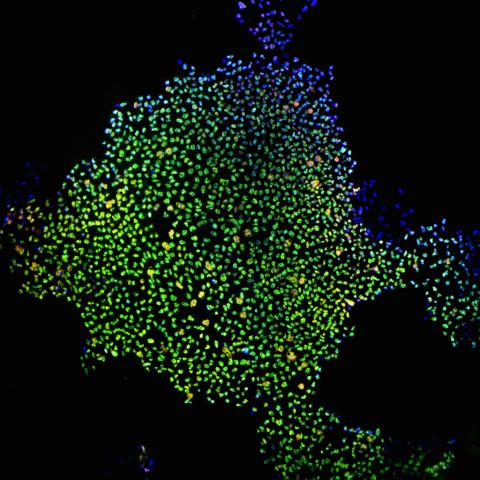

3334: Four timepoints in gastrulation

3334: Four timepoints in gastrulation

It has been said that gastrulation is the most important event in a person's life. This part of early embryonic development transforms a simple ball of cells and begins to define cell fate and the body axis. In a study published in Science magazine, NIGMS grantee Bob Goldstein and his research group studied how contractions of actomyosin filaments in C. elegans and Drosophila embryos lead to dramatic rearrangements of cell and embryonic structure. In these images, myosin (green) and plasma membrane (red) are highlighted at four timepoints in gastrulation in the roundworm C. elegans. The blue highlights in the top three frames show how cells are internalized, and the site of closure around the involuting cells is marked with an arrow in the last frame. See related image 3297.

Bob Goldstein, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

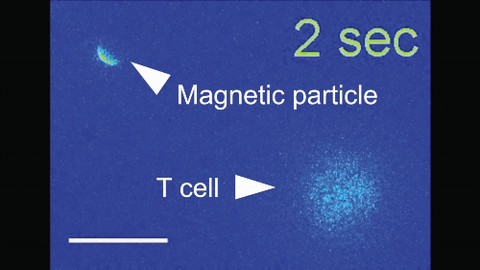

6800: Magnetic Janus particle activating a T cell

6800: Magnetic Janus particle activating a T cell

A Janus particle being used to activate a T cell, a type of immune cell. A Janus particle is a specialized microparticle with different physical properties on its surface, and this one is coated with nickel on one hemisphere and anti-CD3 antibodies (light blue) on the other. The nickel enables the Janus particle to be moved using a magnet, and the antibodies bind to the T cell and activate it. The T cell in this video was loaded with calcium-sensitive dye to visualize calcium influx, which indicates activation. The intensity of calcium influx was color coded so that warmer color indicates higher intensity. Being able to control Janus particles with simple magnets is a step toward controlling individual cells’ activities without complex magnetic devices.

More details can be found in the Angewandte Chemie paper “Remote control of T cell activation using magnetic Janus particles” by Lee et al. This video was captured using epi-fluorescence microscopy.

Related to video 6801.

More details can be found in the Angewandte Chemie paper “Remote control of T cell activation using magnetic Janus particles” by Lee et al. This video was captured using epi-fluorescence microscopy.

Related to video 6801.

Yan Yu, Indiana University, Bloomington.

View Media

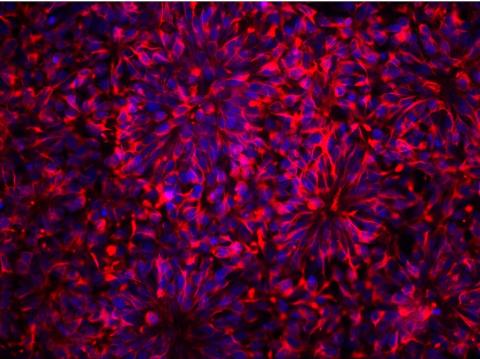

3284: Neurons from human ES cells

3284: Neurons from human ES cells

These neural precursor cells were derived from human embryonic stem cells. The neural cell bodies are stained red, and the nuclei are blue. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Xianmin Zeng lab, Buck Institute for Age Research, via CIRM

View Media

3498: Wound healing in process

3498: Wound healing in process

Wound healing requires the action of stem cells. In mice that lack the Sept2/ARTS gene, stem cells involved in wound healing live longer and wounds heal faster and more thoroughly than in normal mice. This confocal microscopy image from a mouse lacking the Sept2/ARTS gene shows a tail wound in the process of healing. See more information in the article in Science.

Related to images 3497 and 3500.

Related to images 3497 and 3500.

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

5764: Host infection stimulates antibiotic resistance

5764: Host infection stimulates antibiotic resistance

This illustration shows pathogenic bacteria behave like a Trojan horse: switching from antibiotic susceptibility to resistance during infection. Salmonella are vulnerable to antibiotics while circulating in the blood (depicted by fire on red blood cell) but are highly resistant when residing within host macrophages. This leads to treatment failure with the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria.

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call, and the research was funded in part by NIGMS.

View Media

This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call, and the research was funded in part by NIGMS.

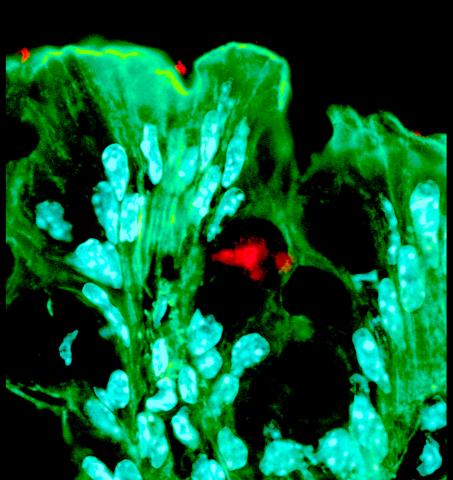

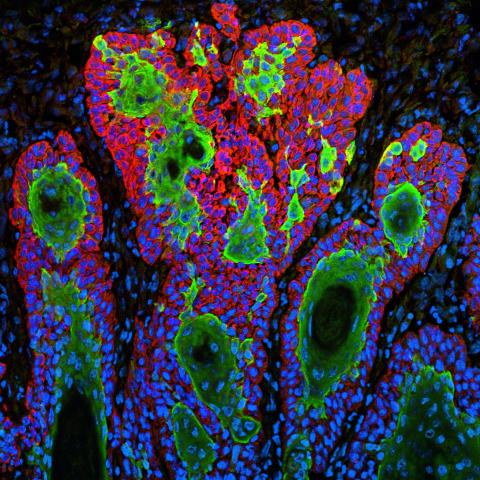

3527: Bacteria in the mouse colon

3527: Bacteria in the mouse colon

Image of the colon of a mouse mono-colonized with Bacteroides fragilis (red) residing within the crypt channel. The red staining is due to an antibody to B. fragilis, the green staining is a general dye for the mouse cells (phalloidin, which stains F-actin) and the light blue glow is from a dye for visualizing the mouse cell nuclei (DAPI, which stains DNA). Bacteria from the human microbiome have evolved specific molecules to physically associate with host tissue, conferring resilience and stability during life-long colonization of the gut. Image is featured in October 2015 Biomedical Beat blog post Cool Images: A Halloween-Inspired Cell Collection.

Sarkis K. Mazmanian, California Institute of Technology

View Media

3758: Dengue virus membrane protein structure

3758: Dengue virus membrane protein structure

Dengue virus is a mosquito-borne illness that infects millions of people in the tropics and subtropics each year. Like many viruses, dengue is enclosed by a protective membrane. The proteins that span this membrane play an important role in the life cycle of the virus. Scientists used cryo-EM to determine the structure of a dengue virus at a 3.5-angstrom resolution to reveal how the membrane proteins undergo major structural changes as the virus matures and infects a host. The image shows a side view of the structure of a protein composed of two smaller proteins, called E and M. Each E and M contributes two molecules to the overall protein structure (called a heterotetramer), which is important for assembling and holding together the viral membrane, i.e., the shell that surrounds the genetic material of the dengue virus. The dengue protein's structure has revealed some portions in the protein that might be good targets for developing medications that could be used to combat dengue virus infections. For more on cryo-EM see the blog post Cryo-Electron Microscopy Reveals Molecules in Ever Greater Detail. You can watch a rotating view of the dengue virus surface structure in video 3748.

Hong Zhou, UCLA

View Media

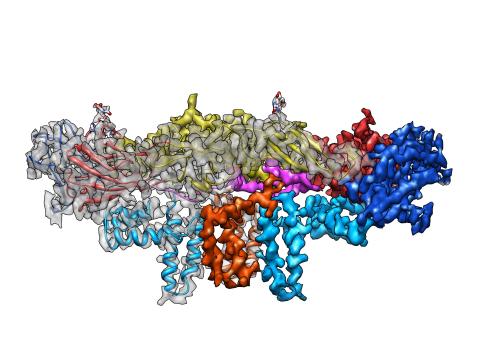

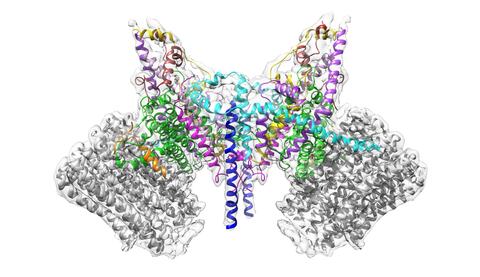

6353: ATP Synthase

6353: ATP Synthase

Atomic model of the membrane region of the mitochondrial ATP synthase built into a cryo-EM map at 3.6 Å resolution. ATP synthase is the primary producer of ATP in aerobic cells. Drugs that inhibit the bacterial ATP synthase, but not the human mitochondrial enzyme, can serve as antibiotics. This therapeutic approach was successfully demonstrated with the bedaquiline, an ATP synthase inhibitor now used in the treatment of extensively drug resistant tuberculosis.

More information about this structure can be found in the Science paper ”Atomic model for the dimeric F0 region of mitochondrial ATP synthase” by Guo et. al.

More information about this structure can be found in the Science paper ”Atomic model for the dimeric F0 region of mitochondrial ATP synthase” by Guo et. al.

Bridget Carragher, <a href="http://nramm.nysbc.org/">NRAMM National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy</a>

View Media

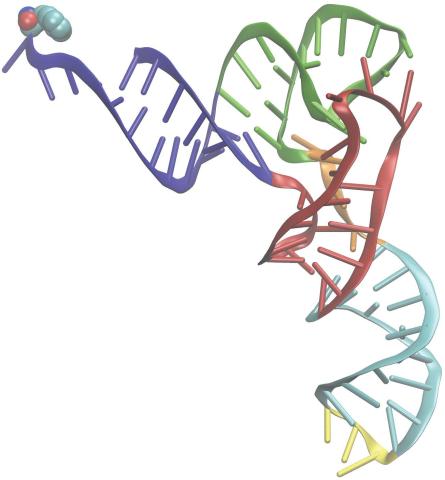

3406: Phenylalanine tRNA molecule

3406: Phenylalanine tRNA molecule

Phenylalanine tRNA showing the anticodon (yellow) and the amino acid, phenylalanine (blue and red spheres).

Patrick O'Donoghue and Dieter Soll, Yale University

View Media

2369: Protein purification robot in action 01

2369: Protein purification robot in action 01

A robot is transferring 96 purification columns to a vacuum manifold for subsequent purification procedures.

The Northeast Collaboratory for Structural Genomics

View Media

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

These cells are induced stem cells made from human adult skin cells that were genetically reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. The induced stem cells were made potentially safer by removing the introduced genes and the viral vector used to ferry genes into the cells, a loop of DNA called a plasmid. The work was accomplished by geneticist Junying Yu in the laboratory of James Thomson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor and the director of regenerative biology for the Morgridge Institute for Research.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

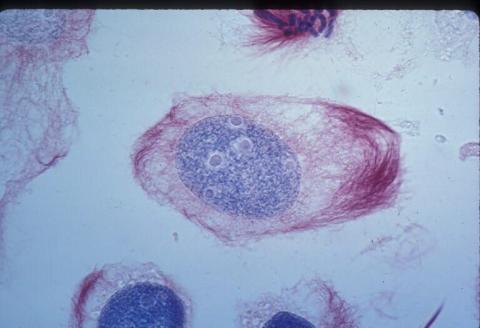

1012: Lily mitosis 02

1012: Lily mitosis 02

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

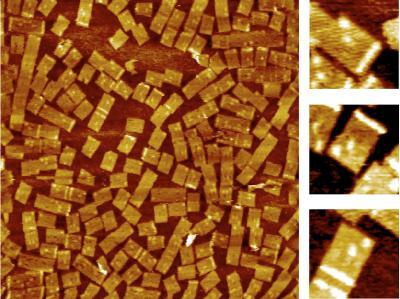

2455: Golden gene chips

2455: Golden gene chips

A team of chemists and physicists used nanotechnology and DNA's ability to self-assemble with matching RNA to create a new kind of chip for measuring gene activity. When RNA of a gene of interest binds to a DNA tile (gold squares), it creates a raised surface (white areas) that can be detected by a powerful microscope. This nanochip approach offers manufacturing and usage advantages over existing gene chips and is a key step toward detecting gene activity in a single cell. Featured in the February 20, 2008, issue of Biomedical Beat.

Hao Yan and Yonggang Ke, Arizona State University

View Media

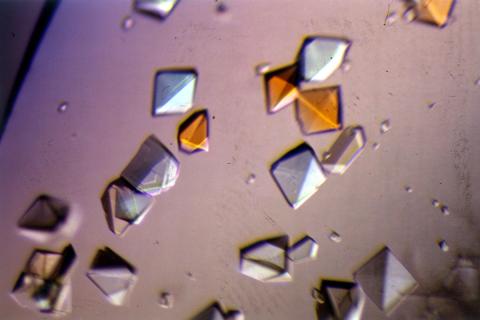

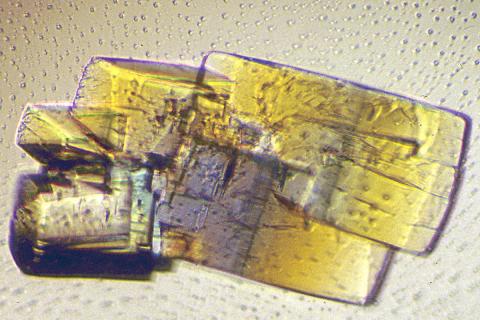

2412: Pig alpha amylase

2412: Pig alpha amylase

Crystals of porcine alpha amylase protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

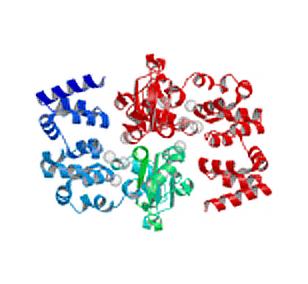

2345: Magnesium transporter protein from E. faecalis

2345: Magnesium transporter protein from E. faecalis

Structure of a magnesium transporter protein from an antibiotic-resistant bacterium (Enterococcus faecalis) found in the human gut. Featured as one of the June 2007 Protein Sructure Initiative Structures of the Month.

New York Structural GenomiX Consortium

View Media

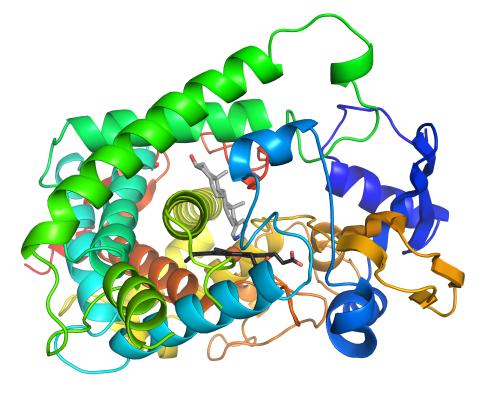

3326: Cytochrome structure with anticancer drug

3326: Cytochrome structure with anticancer drug

This image shows the structure of the CYP17A1 enzyme (ribbons colored from blue N-terminus to red C-terminus), with the associated heme colored black. The prostate cancer drug abiraterone is colored gray. Cytochrome P450 enzymes bind to and metabolize a variety of chemicals, including drugs. Cytochrome P450 17A1 also helps create steroid hormones. Emily Scott's lab is studying how CYP17A1 could be selectively inhibited to treat prostate cancer. She and graduate student Natasha DeVore elucidated the structure shown using X-ray crystallography. Dr. Scott created the image (both white bg and transparent bg) for the NIGMS image gallery. See the "Medium-Resolution Image" for a PNG version of the image that is transparent.

Emily Scott, University of Kansas

View Media

2547: Central dogma, illustrated

2547: Central dogma, illustrated

DNA encodes RNA, which encodes protein. DNA is transcribed to make messenger RNA (mRNA). The mRNA sequence (dark red strand) is complementary to the DNA sequence (blue strand). On ribosomes, transfer RNA (tRNA) reads three nucleotides at a time in mRNA to bring together the amino acids that link up to make a protein. See image 2548 for a labeled version of this illustration and 2549 for a labeled and numbered version. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

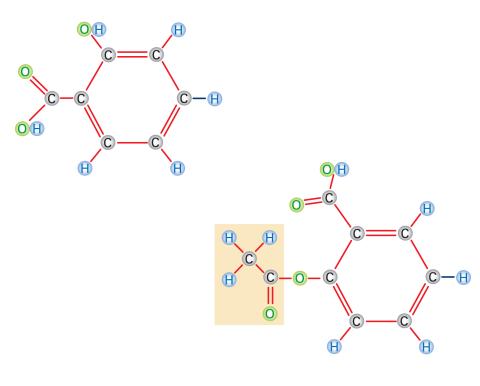

2529: Aspirin

2529: Aspirin

Acetylsalicylate (bottom) is the aspirin of today. Adding a chemical tag called an acetyl group (shaded box, bottom) to a molecule derived from willow bark (salicylate, top) makes the molecule less acidic (and easier on the lining of the digestive tract), but still effective at relieving pain. See image 2530 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

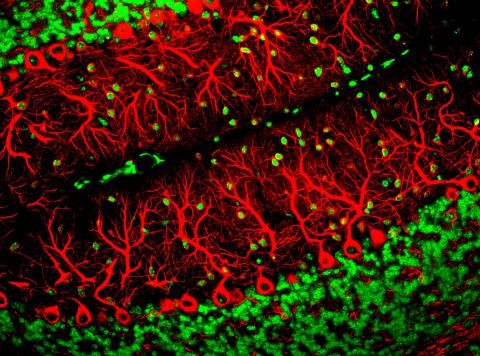

3637: Purkinje cells are one of the main cell types in the brain

3637: Purkinje cells are one of the main cell types in the brain

This image captures Purkinje cells (red), one of the main types of nerve cell found in the brain. These cells have elaborate branching structures called dendrites that receive signals from other nerve cells.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Yinghua Ma and Timothy Vartanian, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y.

View Media

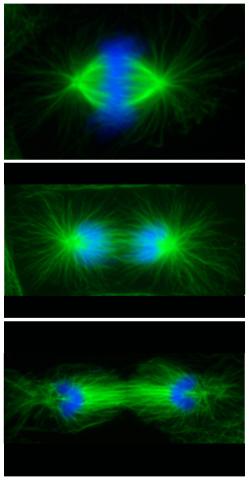

3442: Cell division phases in Xenopus frog cells

3442: Cell division phases in Xenopus frog cells

These images show three stages of cell division in Xenopus XL177 cells, which are derived from tadpole epithelial cells. They are (from top): metaphase, anaphase and telophase. The microtubules are green and the chromosomes are blue. Related to 3443.

Claire Walczak, who took them while working as a postdoc in the laboratory of Timothy Mitchison

View Media

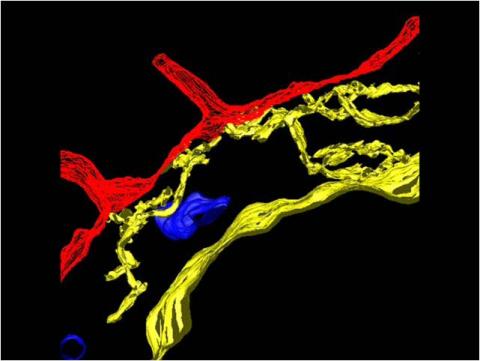

2636: Computer model of cell membrane

2636: Computer model of cell membrane

A computer model of the cell membrane, where the plasma membrane is red, endoplasmic reticulum is yellow, and mitochondria are blue. This image relates to a July 27, 2009 article in Computing Life.

Bridget Wilson, University of New Mexico

View Media

1313: Cell eyes clock

3597: DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC)

3597: DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC)

A study published in March 2012 used cryo-electron microscopy to determine the structure of the DNA replication origin recognition complex (ORC), a semi-circular, protein complex (yellow) that recognizes and binds DNA to start the replication process. The ORC appears to wrap around and bend approximately 70 base pairs of double stranded DNA (red and blue). Also shown is the protein Cdc6 (green), which is also involved in the initiation of DNA replication. Related to video 3307 that shows the structure from different angles. From a Brookhaven National Laboratory news release, "Study Reveals How Protein Machinery Binds and Wraps DNA to Start Replication."

Huilin Li, Brookhaven National Laboratory

View Media

2571: VDAC video 02

2571: VDAC video 02

This video shows the structure of the pore-forming protein VDAC-1 from humans. This molecule mediates the flow of products needed for metabolism--in particular the export of ATP--across the outer membrane of mitochondria, the power plants for eukaryotic cells. VDAC-1 is involved in metabolism and the self-destruction of cells--two biological processes central to health.

Related to videos 2570 and 2572.

Related to videos 2570 and 2572.

Gerhard Wagner, Harvard Medical School

View Media

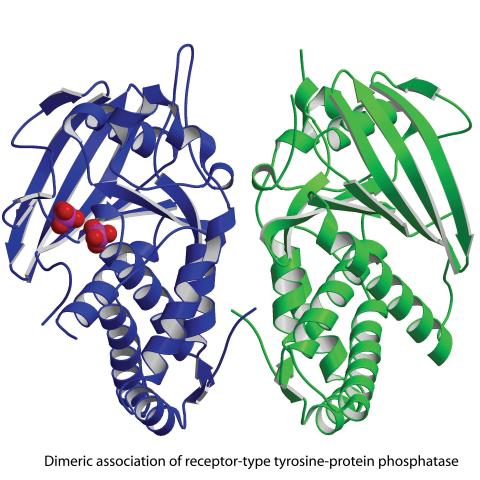

2349: Dimeric association of receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase

2349: Dimeric association of receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase

Model of the catalytic portion of an enzyme, receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase from humans. The enzyme consists of two identical protein subunits, shown in blue and green. The groups made up of purple and red balls represent phosphate groups, chemical groups that can influence enzyme activity. This phosphatase removes phosphate groups from the enzyme tyrosine kinase, counteracting its effects.

New York Structural GenomiX Research Consortium, PSI

View Media

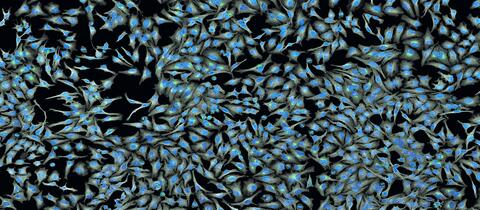

5761: A panorama view of cells

5761: A panorama view of cells

This photograph shows a panoramic view of HeLa cells, a cell line many researchers use to study a large variety of important research questions. The cells' nuclei containing the DNA are stained in blue and the cells' cytoskeletons in gray.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

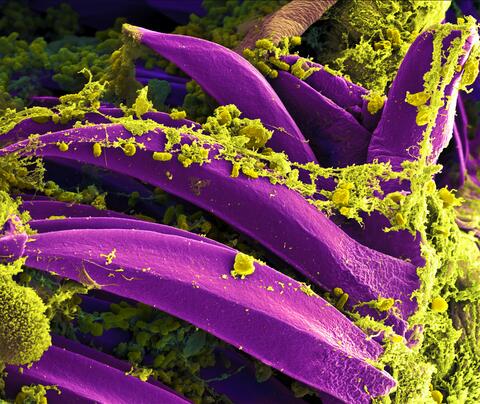

3576: Bubonic plague bacteria on part of the digestive system in a rat flea

3576: Bubonic plague bacteria on part of the digestive system in a rat flea

Here, bubonic plague bacteria (yellow) are shown in the digestive system of a rat flea (purple). The bubonic plague killed a third of Europeans in the mid-14th century. Today, it is still active in Africa, Asia, and the Americas, with as many as 2,000 people infected worldwide each year. If caught early, bubonic plague can be treated with antibiotics.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

NIAID

View Media

3628: Skin cancer cells (squamous cell carcinoma)

3628: Skin cancer cells (squamous cell carcinoma)

This image shows the uncontrolled growth of cells in squamous cell carcinoma, the second most common form of skin cancer. If caught early, squamous cell carcinoma is usually not life-threatening.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Markus Schober and Elaine Fuchs, The Rockefeller University

View Media

2402: RNase A (2)

2402: RNase A (2)

A crystal of RNase A protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

3779: Precisely Delivering Chemical Cargo to Cells

3779: Precisely Delivering Chemical Cargo to Cells

Moving protein or other molecules to specific cells to treat or examine them has been a major biological challenge. Scientists have now developed a technique for delivering chemicals to individual cells. The approach involves gold nanowires that, for example, can carry tumor-killing proteins. The advance was possible after researchers developed electric tweezers that could manipulate gold nanowires to help deliver drugs to single cells.

This movie shows the manipulation of the nanowires for drug delivery to a single cell. To learn more about this technique, see this post in the Computing Life series.

This movie shows the manipulation of the nanowires for drug delivery to a single cell. To learn more about this technique, see this post in the Computing Life series.

Nature Nanotechnology

View Media

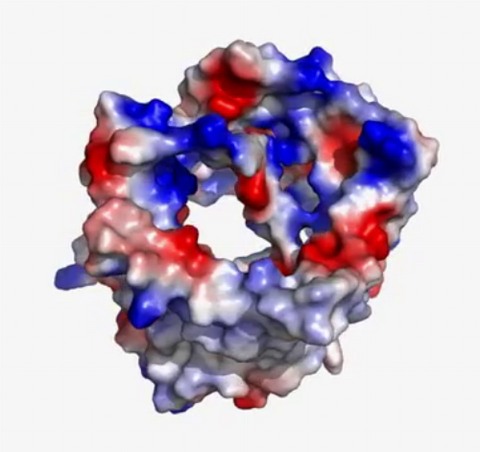

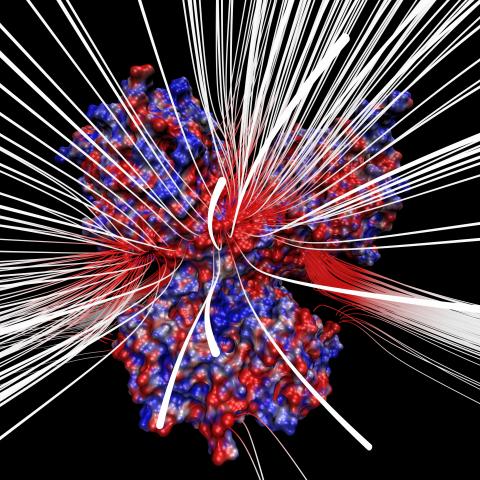

3658: Electrostatic map of human spermine synthase

3658: Electrostatic map of human spermine synthase

From PDB entry 3c6k, Crystal structure of human spermine synthase in complex with spermidine and 5-methylthioadenosine.

Emil Alexov, Clemson University

View Media

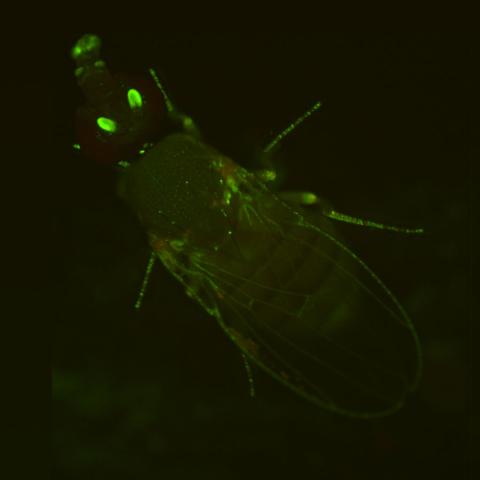

2417: Fly by night

2417: Fly by night

This fruit fly expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the same pattern as the period gene, a gene that regulates circadian rhythm and is expressed in all sensory neurons on the surface of the fly.

Jay Hirsh, University of Virginia

View Media