Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

6776: Tracking cells in a gastrulating zebrafish embryo

6776: Tracking cells in a gastrulating zebrafish embryo

During development, a zebrafish embryo is transformed from a ball of cells into a recognizable body plan by sweeping convergence and extension cell movements. This process is called gastrulation. Each line in this video represents the movement of a single zebrafish embryo cell over the course of 3 hours. The video was created using time-lapse confocal microscopy. Related to image 6775.

Liliana Solnica-Krezel, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

View Media

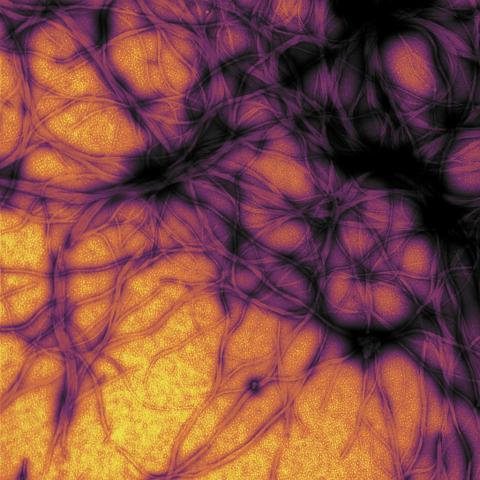

3460: Prion protein fibrils 1

3460: Prion protein fibrils 1

Recombinant proteins such as the prion protein shown here are often used to model how proteins misfold and sometimes polymerize in neurodegenerative disorders. This prion protein was expressed in E. coli, purified and fibrillized at pH 7. Image taken in 2004 for a research project by Roger Moore, Ph.D., at Rocky Mountain Laboratories that was published in 2007 in Biochemistry. This image was not used in the publication.

Ken Pekoc (public affairs officer) and Julie Marquardt, NIAID/ Rocky Mountain Laboratories

View Media

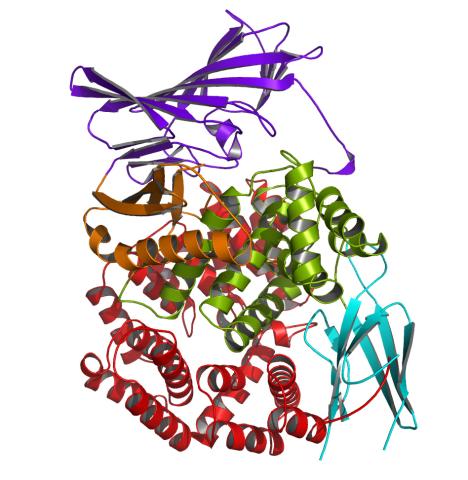

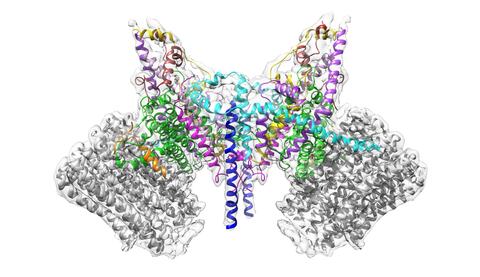

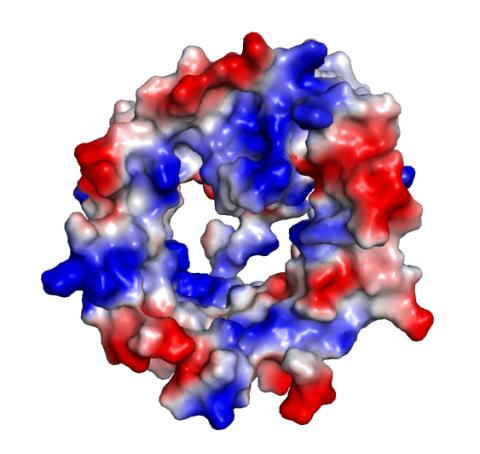

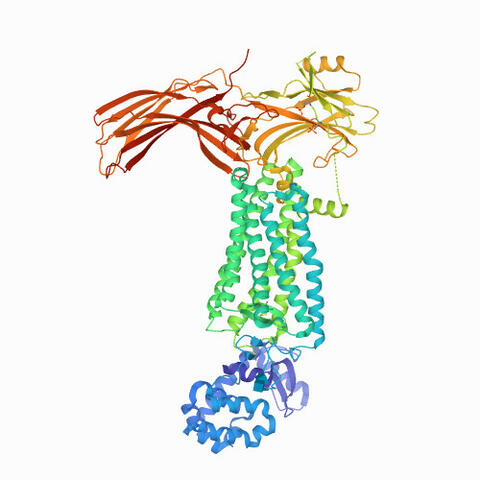

2341: Aminopeptidase N from N. meningitidis

2341: Aminopeptidase N from N. meningitidis

Model of the enzyme aminopeptidase N from the human pathogen Neisseria meningitidis, which can cause meningitis epidemics. The structure provides insight on the active site of this important molecule.

Midwest Center for Structural Genomics, PSI

View Media

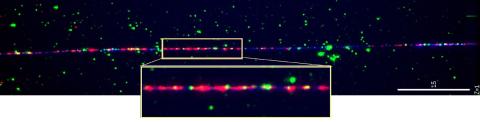

2475: Chromosome fiber 01

2475: Chromosome fiber 01

This microscopic image shows a chromatin fiber--a DNA molecule bound to naturally occurring proteins.

Marc Green and Susan Forsburg, University of Southern California

View Media

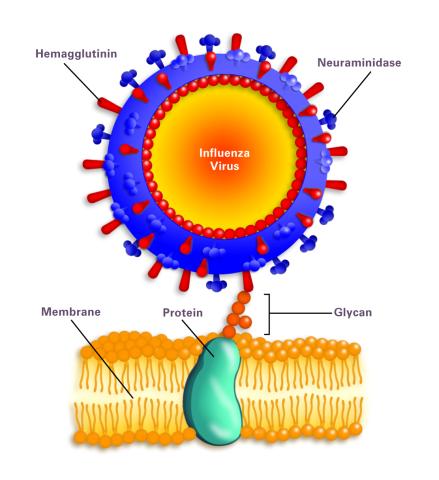

2505: Influenza virus attaches to host membrane (with labels)

2505: Influenza virus attaches to host membrane (with labels)

Influenza A infects a host cell when hemagglutinin grips onto glycans on its surface. Neuraminidase, an enzyme that chews sugars, helps newly made virus particles detach so they can infect other cells. Related to 213.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

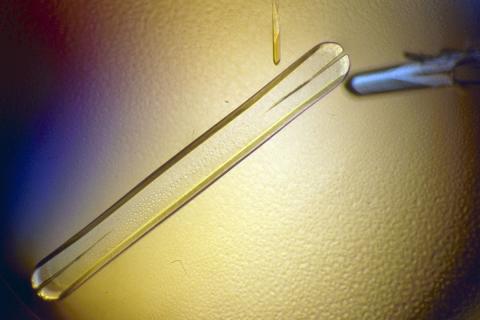

2397: Bovine milk alpha-lactalbumin (1)

2397: Bovine milk alpha-lactalbumin (1)

A crystal of bovine milk alpha-lactalbumin protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

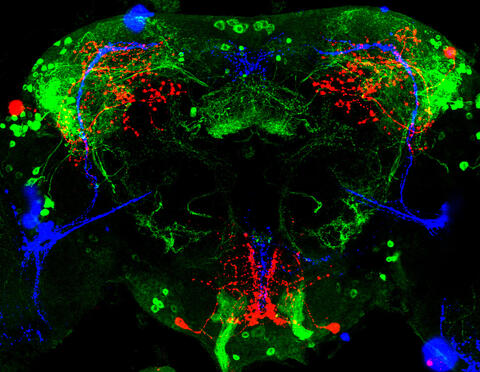

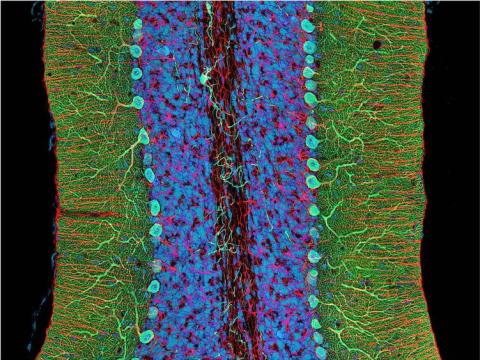

3754: Circadian rhythm neurons in the fruit fly brain

3754: Circadian rhythm neurons in the fruit fly brain

Some nerve cells (neurons) in the brain keep track of the daily cycle. This time-keeping mechanism, called the circadian clock, is found in all animals including us. The circadian clock controls our daily activities such as sleep and wakefulness. Researchers are interested in finding the neuron circuits involved in this time keeping and how the information about daily time in the brain is relayed to the rest of the body. In this image of a brain of the fruit fly Drosophila the time-of-day information flowing through the brain has been visualized by staining the neurons involved: clock neurons (shown in blue) function as "pacemakers" by communicating with neurons that produce a short protein called leucokinin (LK) (red), which, in turn, relays the time signal to other neurons, called LK-R neurons (green). This signaling cascade set in motion by the pacemaker neurons helps synchronize the fly's daily activity with the 24-hour cycle. To learn more about what scientists have found out about circadian pacemaker neurons in the fruit fly see this news release by New York University. This work was featured in the Biomedical Beat blog post Cool Image: A Circadian Circuit.

Justin Blau, New York University

View Media

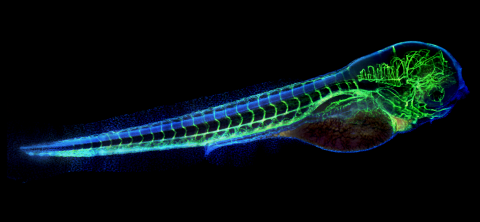

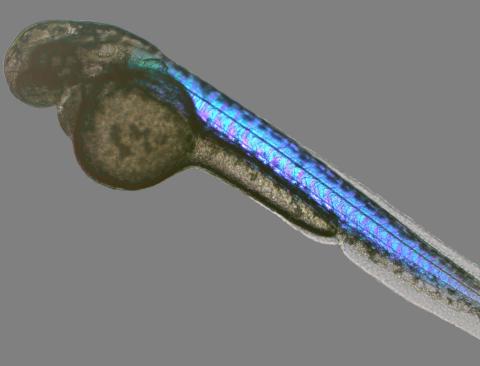

6661: Zebrafish embryo showing vasculature

6661: Zebrafish embryo showing vasculature

A zebrafish embryo. The blue areas are cell bodies, the green lines are blood vessels, and the red glow is blood. This image was created by stitching together five individual images captured with a hyperspectral multipoint confocal fluorescence microscope that was developed at the Eliceiri Lab.

Kevin Eliceiri, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

View Media

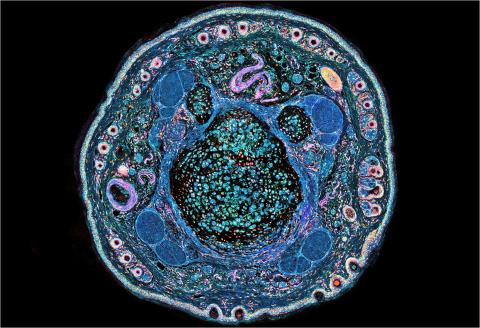

3395: NCMIR mouse tail

3395: NCMIR mouse tail

Stained cross section of a mouse tail.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

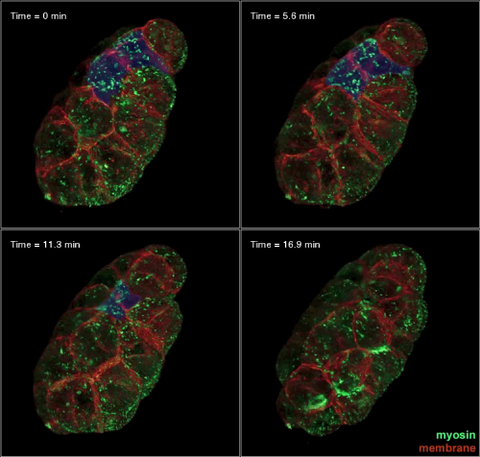

3334: Four timepoints in gastrulation

3334: Four timepoints in gastrulation

It has been said that gastrulation is the most important event in a person's life. This part of early embryonic development transforms a simple ball of cells and begins to define cell fate and the body axis. In a study published in Science magazine, NIGMS grantee Bob Goldstein and his research group studied how contractions of actomyosin filaments in C. elegans and Drosophila embryos lead to dramatic rearrangements of cell and embryonic structure. In these images, myosin (green) and plasma membrane (red) are highlighted at four timepoints in gastrulation in the roundworm C. elegans. The blue highlights in the top three frames show how cells are internalized, and the site of closure around the involuting cells is marked with an arrow in the last frame. See related image 3297.

Bob Goldstein, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

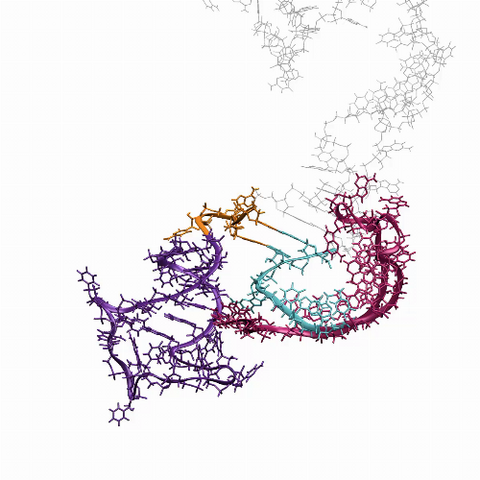

6625: RNA folding in action

6625: RNA folding in action

An RNA molecule dynamically refolds itself as it is being synthesized. When the RNA is short, it ties itself into a “knot” (dark purple). For this domain to slip its knot, about 5 seconds into the video, another newly forming region (fuchsia) wiggles down to gain a “toehold.” About 9 seconds in, the temporarily knotted domain untangles and unwinds. Finally, at about 23 seconds, the strand starts to be reconfigured into the shape it needs to do its job in the cell.

Julius Lucks, Northwestern University

View Media

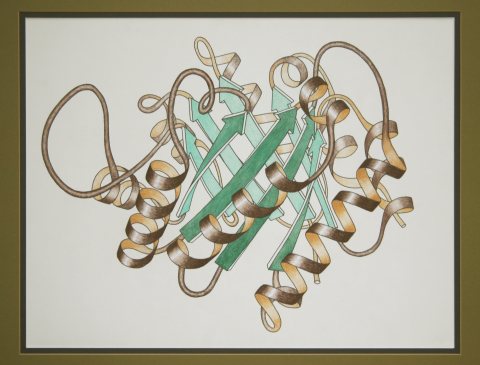

2748: Early ribbon drawing of a protein

2748: Early ribbon drawing of a protein

This ribbon drawing of a protein hand drawn and colored by researcher Jane Richardson in 1981 helped originate the ribbon representation of proteins that is now ubiquitous in molecular graphics. The drawing shows the 3-dimensional structure of the protein triose phosphate isomerase. The green arrows represent the barrel of eight beta strands in this structure and the brown spirals show the protein's eight alpha helices. A black and white version of this drawing originally illustrated a review article in Advances in Protein Chemistry, volume 34, titled "Anatomy and Taxonomy of Protein Structures." The illustration was selected as Picture of The Day on the English Wikipedia for November 19, 2009. Other important and beautiful images of protein structures by Jane Richardson are available in her Wikimedia gallery.

Jane Richardson, Duke University Medical Center

View Media

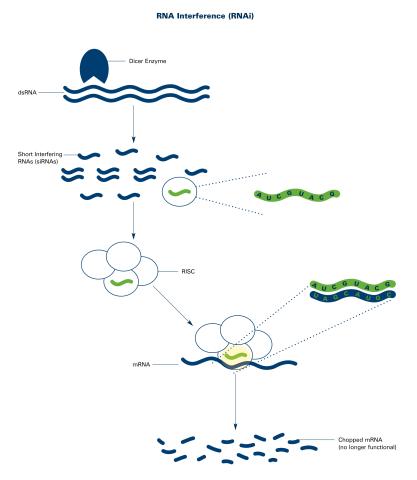

2559: RNA interference (with labels)

2559: RNA interference (with labels)

RNA interference or RNAi is a gene-silencing process in which double-stranded RNAs trigger the destruction of specific RNAs. See 2558 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

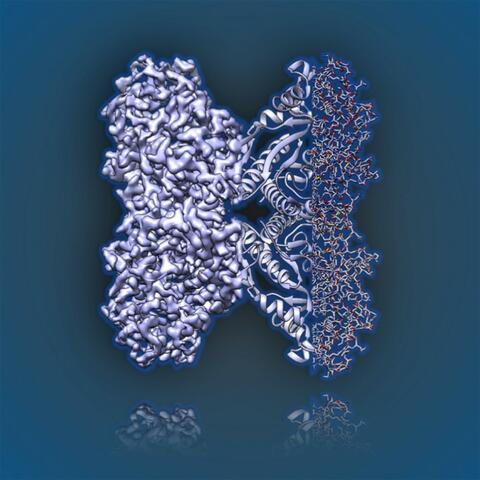

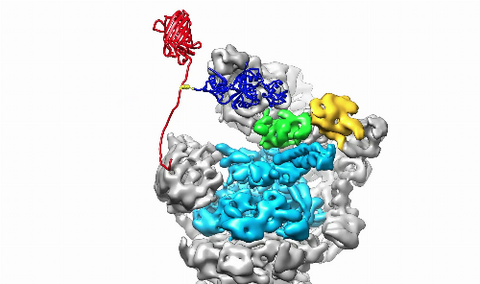

6353: ATP Synthase

6353: ATP Synthase

Atomic model of the membrane region of the mitochondrial ATP synthase built into a cryo-EM map at 3.6 Å resolution. ATP synthase is the primary producer of ATP in aerobic cells. Drugs that inhibit the bacterial ATP synthase, but not the human mitochondrial enzyme, can serve as antibiotics. This therapeutic approach was successfully demonstrated with the bedaquiline, an ATP synthase inhibitor now used in the treatment of extensively drug resistant tuberculosis.

More information about this structure can be found in the Science paper ”Atomic model for the dimeric F0 region of mitochondrial ATP synthase” by Guo et. al.

More information about this structure can be found in the Science paper ”Atomic model for the dimeric F0 region of mitochondrial ATP synthase” by Guo et. al.

Bridget Carragher, <a href="http://nramm.nysbc.org/">NRAMM National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy</a>

View Media

2809: Vimentin in a quail embryo

2809: Vimentin in a quail embryo

Video of high-resolution confocal images depicting vimentin immunofluorescence (green) and nuclei (blue) at the edge of a quail embryo yolk. These images were obtained as part of a study to understand cell migration in embryos. An NIGMS grant to Professor Garcia was used to purchase the confocal microscope that collected these images. Related to images 2807 and 2808.

Andrés Garcia, Georgia Tech

View Media

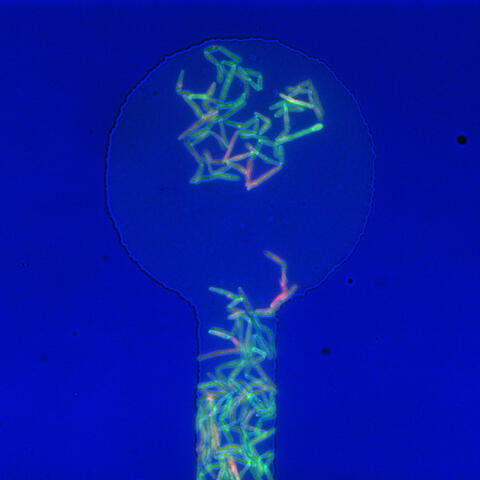

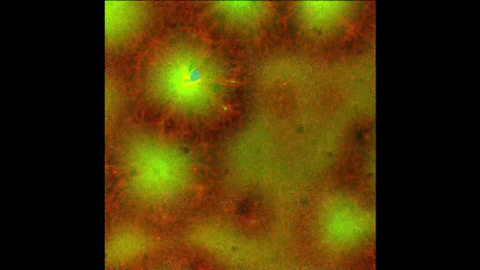

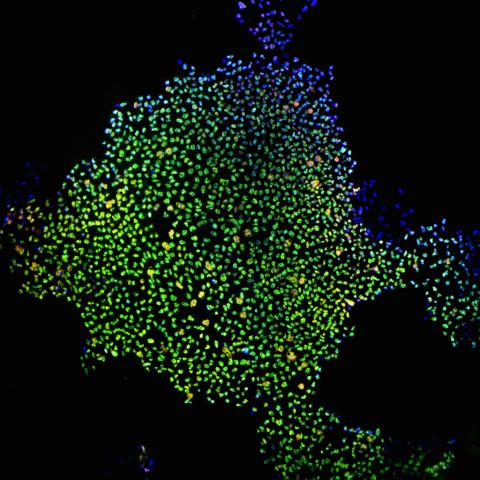

5751: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 1

5751: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 1

Antibiotic resistance in microbes is a serious health concern. So researchers have turned their attention to how bacteria undo the action of some antibiotics. Here, scientists set out to find the conditions that help individual bacterial cells survive in the presence of the antibiotic rifampicin. The research team used Mycobacterium smegmatis, a more harmless relative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which infects the lung and other organs and causes serious disease.

In this image, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to video 5752.

In this image, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to video 5752.

Bree Aldridge, Tufts University

View Media

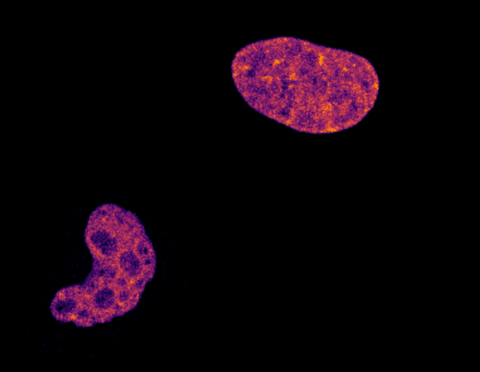

6790: Cell division and cell death

6790: Cell division and cell death

Two cells over a 2-hour period. The one on the bottom left goes through programmed cell death, also known as apoptosis. The one on the top right goes through cell division, also called mitosis. This video was captured using a confocal microscope.

Dylan T. Burnette, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

View Media

6555: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 2)

6555: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 2)

Floral pattern emerging as two bacterial species, motile Acinetobacter baylyi (red) and non-motile Escherichia coli (green), are grown together for 48 hours on 1% agar surface from a small inoculum in the center of a Petri dish.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

L. Xiong et al, eLife 2020;9: e48885

View Media

6590: Cell-like compartments emerging from scrambled frog eggs 4

6590: Cell-like compartments emerging from scrambled frog eggs 4

Cell-like compartments that spontaneously emerged from scrambled frog eggs, with nuclei (blue) from frog sperm. Endoplasmic reticulum (red) and microtubules (green) are also visible. Video created using confocal microscopy.

For more photos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6584, 6585, 6586, 6591, 6592, and 6593.

For videos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6587, 6588, 6589.

Xianrui Cheng, Stanford University School of Medicine.

View Media

2335: Virtual snow world

2335: Virtual snow world

Glide across an icy canyon, where you see smiling snowmen and waddling penguins. Toss a snowball, hear it smash against an igloo, and then watch it explode in bright colors. Psychologists David Patterson and Hunter Hoffman of the University of Washington in Seattle developed this virtual "Snow World" to test whether immersing someone in a pretend reality could ease pain during burn treatment and other medical procedures. They found that people fully engaged in the virtual reality experience reported 60 percent less pain. The technology offers a promising way to manage pain.

David Patterson and Hunter Hoffmann, University of Washington

View Media

2495: VDAC-1 (4)

2495: VDAC-1 (4)

The structure of the pore-forming protein VDAC-1 from humans. This molecule mediates the flow of products needed for metabolism--in particular the export of ATP--across the outer membrane of mitochondria, the power plants for eukaryotic cells. VDAC-1 is involved in metabolism and the self-destruction of cells--two biological processes central to health.

Related to images 2491, 2494, and 2488.

Related to images 2491, 2494, and 2488.

Gerhard Wagner, Harvard Medical School

View Media

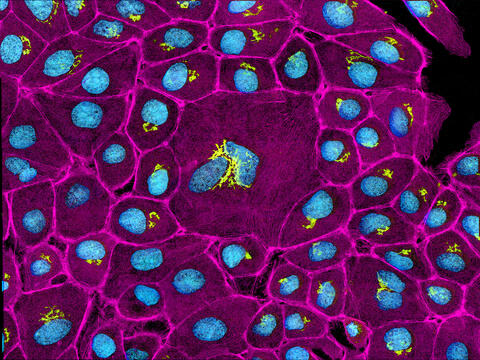

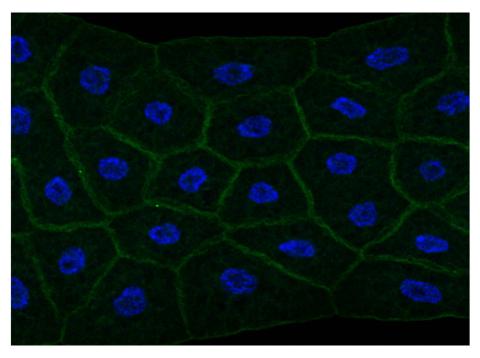

3647: Epithelial cells

3647: Epithelial cells

This image mostly shows normal cultured epithelial cells expressing green fluorescent protein targeted to the Golgi apparatus (yellow-green) and stained for actin (magenta) and DNA (cyan). The middle cell is an abnormal large multinucleated cell. All the cells in this image have a Golgi but not all are expressing the targeted recombinant fluorescent protein.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

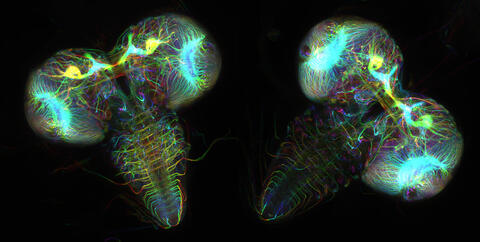

6808: Fruit fly larvae brains showing tubulin

6808: Fruit fly larvae brains showing tubulin

Two fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) larvae brains with neurons expressing fluorescently tagged tubulin protein. Tubulin makes up strong, hollow fibers called microtubules that play important roles in neuron growth and migration during brain development. This image was captured using confocal microscopy, and the color indicates the position of the neurons within the brain.

Vladimir I. Gelfand, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

View Media

6768: Rhodopsin bound to visual arrestin

6768: Rhodopsin bound to visual arrestin

Rhodopsin is a pigment in the rod cells of the retina (back of the eye). It is extremely light-sensitive, supporting vision in low-light conditions. Here, it is attached to arrestin, a protein that sends signals in the body. This structure was determined using an X-ray free electron laser.

Protein Data Bank.

View Media

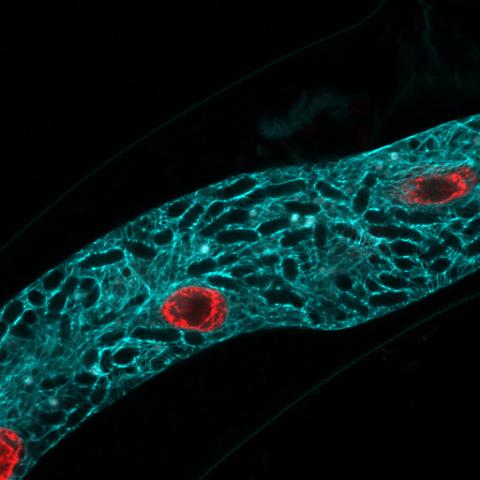

5778: Microsporidia in roundworm 2

5778: Microsporidia in roundworm 2

Many disease-causing microbes manipulate their host’s metabolism and cells for their own ends. Microsporidia—which are parasites closely related to fungi—infect and multiply inside animal cells, and take the rearranging of cells’ interiors to a new level. They reprogram animal cells such that the cells start to fuse, causing them to form long, continuous tubes. As shown in this image of the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, microsporidia (dark oval shapes) invaded the worm’s gut cells (long tube; the cell nuclei are shown in red) and have instructed the cells to merge. The cell fusion enables the microsporidia to thrive and propagate in the expanded space. Scientists study microsporidia in worms to gain more insight into how these parasites manipulate their host cells. This knowledge might help researchers devise strategies to prevent or treat infections with microsporidia.

For more on the research into microsporidia, see this news release from the University of California San Diego. Related to images 5777 and 5779.

For more on the research into microsporidia, see this news release from the University of California San Diego. Related to images 5777 and 5779.

Keir Balla and Emily Troemel, University of California San Diego

View Media

6518: Biofilm formed by a pathogen

6518: Biofilm formed by a pathogen

A biofilm is a highly organized community of microorganisms that develops naturally on certain surfaces. These communities are common in natural environments and generally do not pose any danger to humans. Many microbes in biofilms have a positive impact on the planet and our societies. Biofilms can be helpful in treatment of wastewater, for example. This dime-sized biofilm, however, was formed by the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Under some conditions, this bacterium can infect wounds that are caused by severe burns. The bacterial cells release a variety of materials to form an extracellular matrix, which is stained red in this photograph. The matrix holds the biofilm together and protects the bacteria from antibiotics and the immune system.

Scott Chimileski, Ph.D., and Roberto Kolter, Ph.D., Harvard Medical School.

View Media

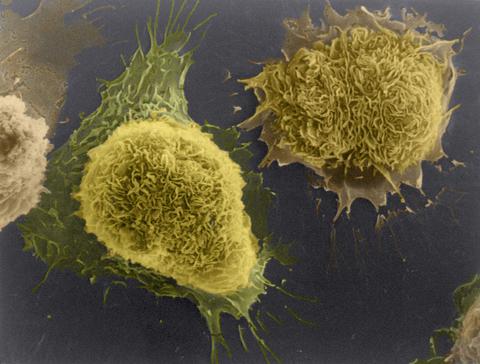

1178: Cultured cells

1178: Cultured cells

This image of laboratory-grown cells was taken with the help of a scanning electron microscope, which yields detailed images of cell surfaces.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

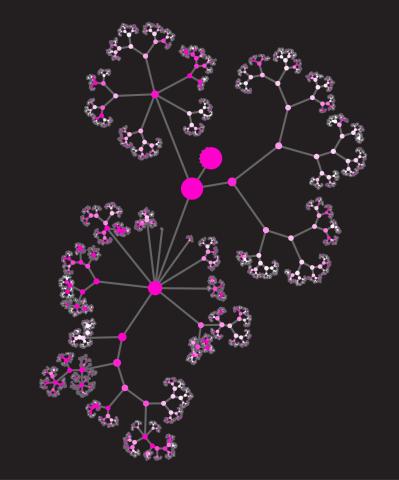

3436: Network diagram of genes, cellular components and processes (unlabeled)

3436: Network diagram of genes, cellular components and processes (unlabeled)

This image shows the hierarchical ontology of genes, cellular components and processes derived from large genomic datasets. From Dutkowski et al. A gene ontology inferred from molecular networks Nat Biotechnol. 2013 Jan;31(1):38-45. Related to 3437.

Janusz Dutkowski and Trey Ideker

View Media

6350: Aldolase

6350: Aldolase

2.5Å resolution reconstruction of rabbit muscle aldolase collected on a FEI/Thermo Fisher Titan Krios with energy filter and image corrector.

National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy http://nramm.nysbc.org/nramm-images/ Source: Bridget Carragher

View Media

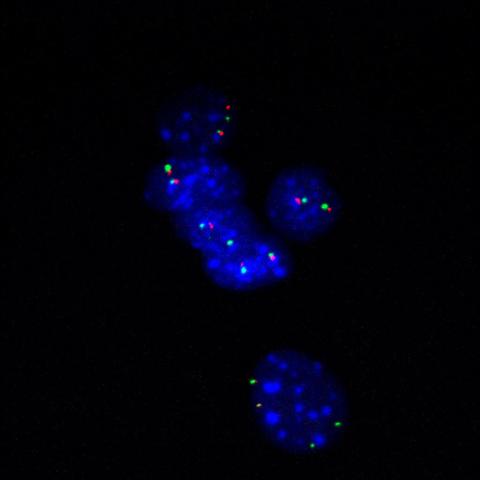

3296: Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in mouse ES cells shows DNA interactions

3296: Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in mouse ES cells shows DNA interactions

Researchers used fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to confirm the presence of long range DNA-DNA interactions in mouse embryonic stem cells. Here, two loci labeled in green (Oct4) and red that are 13 Mb apart on linear DNA are frequently found to be in close proximity. DNA-DNA colocalizations like this are thought to both reflect and contribute to cell type specific gene expression programs.

Kathrin Plath, University of California, Los Angeles

View Media

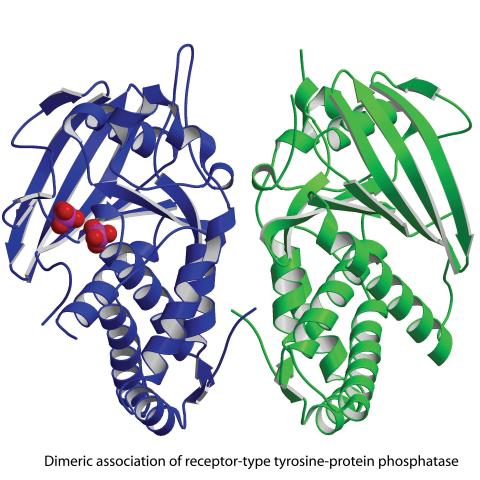

2349: Dimeric association of receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase

2349: Dimeric association of receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase

Model of the catalytic portion of an enzyme, receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase from humans. The enzyme consists of two identical protein subunits, shown in blue and green. The groups made up of purple and red balls represent phosphate groups, chemical groups that can influence enzyme activity. This phosphatase removes phosphate groups from the enzyme tyrosine kinase, counteracting its effects.

New York Structural GenomiX Research Consortium, PSI

View Media

2757: Draper, shown in the fatbody of a Drosophila melanogaster larva

2757: Draper, shown in the fatbody of a Drosophila melanogaster larva

The fly fatbody is a nutrient storage and mobilization organ akin to the mammalian liver. The engulfment receptor Draper (green) is located at the cell surface of fatbody cells. The cell nuclei are shown in blue.

Christina McPhee and Eric Baehrecke, University of Massachusetts Medical School

View Media

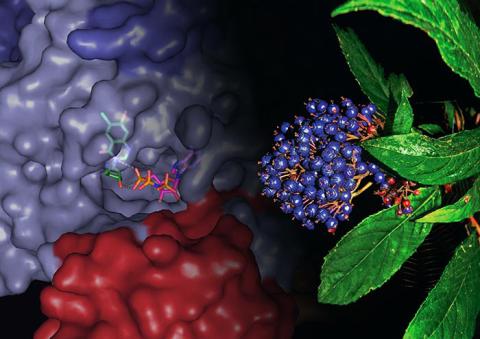

3483: Chang Shan

3483: Chang Shan

For thousands of years, Chinese herbalists have treated malaria using Chang Shan, a root extract from a type of hydrangea that grows in Tibet and Nepal. Recent studies have suggested Chang Shan can also reduce scar formation, treat multiple sclerosis and even slow cancer progression.

Paul Schimmel Lab, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

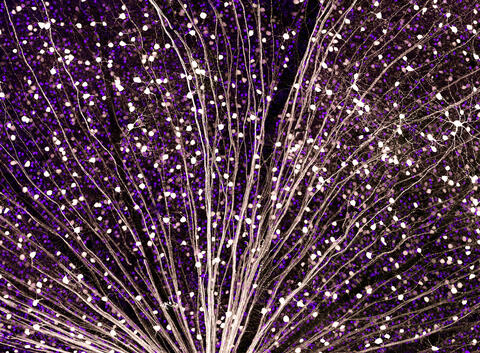

3371: Mouse cerebellum close-up

3371: Mouse cerebellum close-up

The cerebellum is the brain's locomotion control center. Every time you shoot a basketball, tie your shoe or chop an onion, your cerebellum fires into action. Found at the base of your brain, the cerebellum is a single layer of tissue with deep folds like an accordion. People with damage to this region of the brain often have difficulty with balance, coordination and fine motor skills. For a lower magnification, see image 3639.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

5872: Mouse retina close-up

5872: Mouse retina close-up

Keunyoung ("Christine") Kim National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

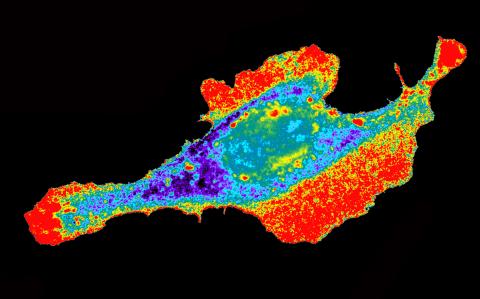

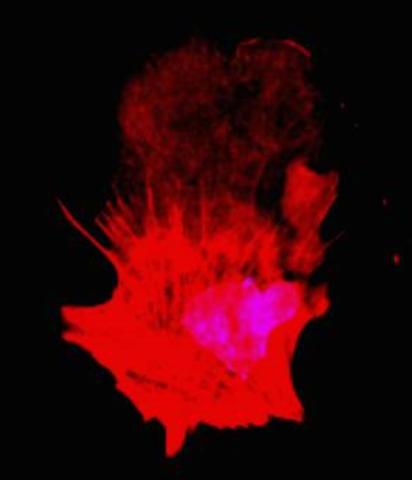

2453: Seeing signaling protein activation in cells 03

2453: Seeing signaling protein activation in cells 03

Cdc42, a member of the Rho family of small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) proteins, regulates multiple cell functions, including motility, proliferation, apoptosis, and cell morphology. In order to fulfill these diverse roles, the timing and location of Cdc42 activation must be tightly controlled. Klaus Hahn and his research group use special dyes designed to report protein conformational changes and interactions, here in living neutrophil cells. Warmer colors in this image indicate higher levels of activation. Cdc42 looks to be activated at cell protrusions.

Related to images 2451, 2452, and 2454.

Related to images 2451, 2452, and 2454.

Klaus Hahn, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Medical School

View Media

5843: Color coding of the Drosophila brain - video

5843: Color coding of the Drosophila brain - video

This video results from a research project to visualize which regions of the adult fruit fly (Drosophila) brain derive from each neural stem cell. First, researchers collected several thousand fruit fly larvae and fluorescently stained a random stem cell in the brain of each. The idea was to create a population of larvae in which each of the 100 or so neural stem cells was labeled at least once. When the larvae grew to adults, the researchers examined the flies’ brains using confocal microscopy. With this technique, the part of a fly’s brain that derived from a single, labeled stem cell “lights up.” The scientists photographed each brain and digitally colorized its lit-up area. By combining thousands of such photos, they created a three-dimensional, color-coded map that shows which part of the Drosophila brain comes from each of its ~100 neural stem cells. In other words, each colored region shows which neurons are the progeny or “clones” of a single stem cell. This work established a hierarchical structure as well as nomenclature for the neurons in the Drosophila brain. Further research will relate functions to structures of the brain.

Related to images 5838 and 5868.

Related to images 5838 and 5868.

Yong Wan from Charles Hansen’s lab, University of Utah. Data preparation and visualization by Masayoshi Ito in the lab of Kei Ito, University of Tokyo.

View Media

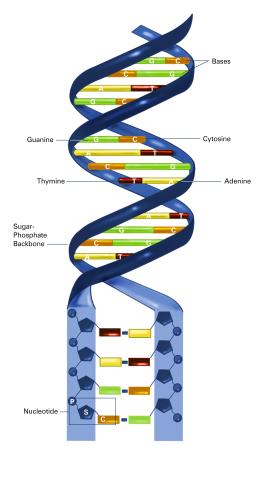

2542: Nucleotides make up DNA (with labels)

2542: Nucleotides make up DNA (with labels)

DNA consists of two long, twisted chains made up of nucleotides. Each nucleotide contains one base, one phosphate molecule, and the sugar molecule deoxyribose. The bases in DNA nucleotides are adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. See image 2541 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

1337: Bicycling cell

1337: Bicycling cell

A humorous treatment of the concept of a cycling cell.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

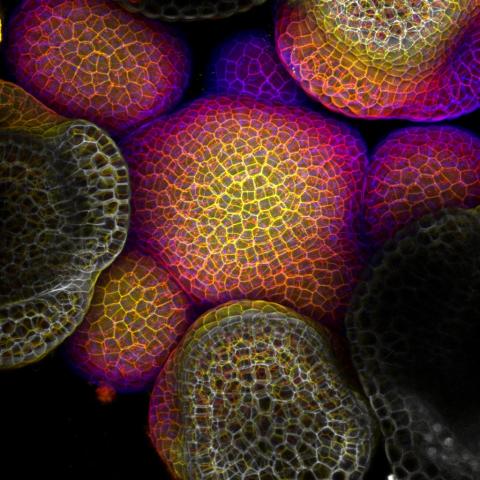

3606: Flower-forming cells in a small plant related to cabbage (Arabidopsis)

3606: Flower-forming cells in a small plant related to cabbage (Arabidopsis)

In plants, as in animals, stem cells can transform into a variety of different cell types. The stem cells at the growing tip of this Arabidopsis plant will soon become flowers. Arabidopsis is frequently studied by cellular and molecular biologists because it grows rapidly (its entire life cycle is only 6 weeks), produces lots of seeds, and has a genome that is easy to manipulate.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Arun Sampathkumar and Elliot Meyerowitz, California Institute of Technology

View Media

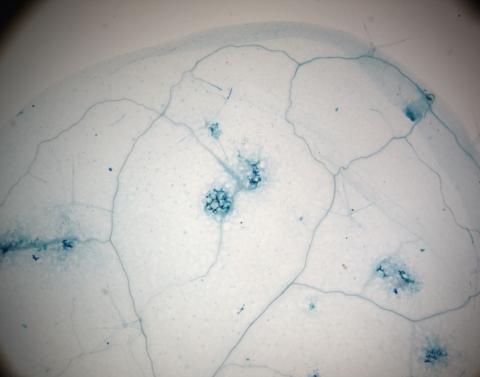

2781: Disease-resistant Arabidopsis leaf

2781: Disease-resistant Arabidopsis leaf

This is a magnified view of an Arabidopsis thaliana leaf a few days after being exposed to the pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. The plant from which this leaf was taken is genetically resistant to the pathogen. The spots in blue show areas of localized cell death where infection occurred, but it did not spread. Compare this response to that shown in Image 2782. Jeff Dangl has been funded by NIGMS to study the interactions between pathogens and hosts that allow or suppress infection.

Jeff Dangl, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

3284: Neurons from human ES cells

3284: Neurons from human ES cells

These neural precursor cells were derived from human embryonic stem cells. The neural cell bodies are stained red, and the nuclei are blue. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Xianmin Zeng lab, Buck Institute for Age Research, via CIRM

View Media

2443: Mapping human genetic variation

2443: Mapping human genetic variation

This map paints a colorful portrait of human genetic variation around the world. Researchers analyzed the DNA of 485 people and tinted the genetic types in different colors to produce one of the most detailed maps of its kind ever made. The map shows that genetic variation decreases with increasing distance from Africa, which supports the idea that humans originated in Africa, spread to the Middle East, then to Asia and Europe, and finally to the Americas. The data also offers a rich resource that scientists could use to pinpoint the genetic basis of diseases prevalent in diverse populations. Featured in the March 19, 2008, issue of Biomedical Beat.

Noah Rosenberg and Martin Soave, University of Michigan

View Media

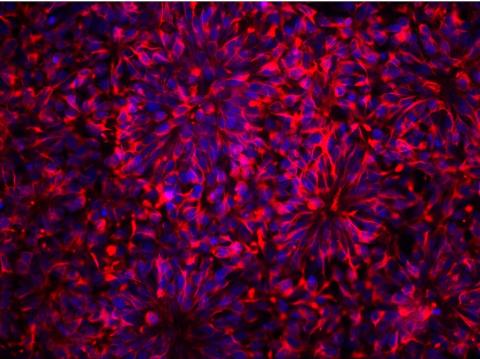

3332: Polarized cells- 01

3332: Polarized cells- 01

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red) and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells with lamellipodia leading edge. Related to images 3328, 3329, 3330, 3331, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

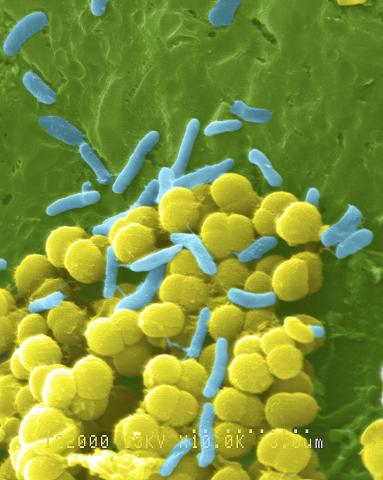

1158: Bacteria shapes

1158: Bacteria shapes

A colorized scanning electron micrograph of bacteria. Scanning electron microscopes allow scientists to see the three-dimensional surface of their samples.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

3718: A Bacillus subtilis biofilm grown in a Petri dish

3718: A Bacillus subtilis biofilm grown in a Petri dish

Bacterial biofilms are tightly knit communities of bacterial cells growing on, for example, solid surfaces, such as in water pipes or on teeth. Here, cells of the bacterium Bacillus subtilis have formed a biofilm in a laboratory culture. Researchers have discovered that the bacterial cells in a biofilm communicate with each other through electrical signals via specialized potassium ion channels to share resources, such as nutrients, with each other. This insight may help scientists to improve sanitation systems to prevent biofilms, which often resist common treatments, from forming and to develop better medicines to combat bacterial infections. See the Biomedical Beat blog post Bacterial Biofilms: A Charged Environment for more information.

Gürol Süel, UCSD

View Media

2667: Glowing fish

2667: Glowing fish

Professor Marc Zimmer's family pets, including these fish, glow in the dark in response to blue light. Featured in the September 2009 issue of Findings.

View Media

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

2604: Induced stem cells from adult skin 02

These cells are induced stem cells made from human adult skin cells that were genetically reprogrammed to mimic embryonic stem cells. The induced stem cells were made potentially safer by removing the introduced genes and the viral vector used to ferry genes into the cells, a loop of DNA called a plasmid. The work was accomplished by geneticist Junying Yu in the laboratory of James Thomson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health professor and the director of regenerative biology for the Morgridge Institute for Research.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

3764: Movie of the 19S proteasome subunit processing a protein substrate

3764: Movie of the 19S proteasome subunit processing a protein substrate

The proteasome is a critical multiprotein complex in the cell that breaks down and recycles proteins that have become damaged or are no longer needed. This movie shows how a protein substrate (red) is bound through its ubiquitin chain (blue) to one of the ubiquitin receptors of the proteasome (Rpn10, yellow). The substrate's flexible engagement region then gets engaged by the AAA+ motor of the proteasome (cyan), which initiates mechanical pulling, unfolding and movement of the protein into the proteasome's interior for cleavage into shorter protein pieces called peptides. During movement of the substrate, its ubiquitin modification gets cleaved off by the deubiquitinase Rpn11 (green), which sits directly above the entrance to the AAA+ motor pore and acts as a gatekeeper to ensure efficient ubiquitin removal, a prerequisite for fast protein breakdown by the 26S proteasome. Related to image 3763.

Andreas Martin, HHMI

View Media

6897: Zebrafish embryo

6897: Zebrafish embryo

A zebrafish embryo showing its natural colors. Zebrafish have see-through eggs and embryos, making them ideal research organisms for studying the earliest stages of development. This image was taken in transmitted light under a polychromatic polarizing microscope.

Michael Shribak, Marine Biological Laboratory/University of Chicago.

View Media