Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

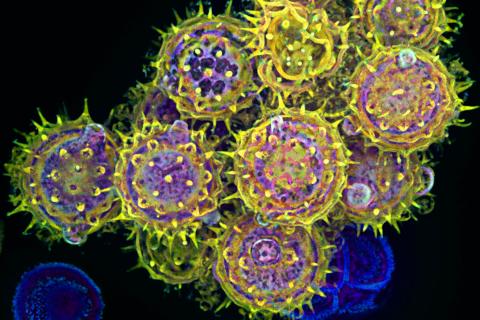

3609: Pollen grains: male germ cells in plants and a cause of seasonal allergies

3609: Pollen grains: male germ cells in plants and a cause of seasonal allergies

Those of us who get sneezy and itchy-eyed every spring or fall may have pollen grains, like those shown here, to blame. Pollen grains are the male germ cells of plants, released to fertilize the corresponding female plant parts. When they are instead inhaled into human nasal passages, they can trigger allergies.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Edna, Gil, and Amit Cukierman, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Philadelphia, Pa.

View Media

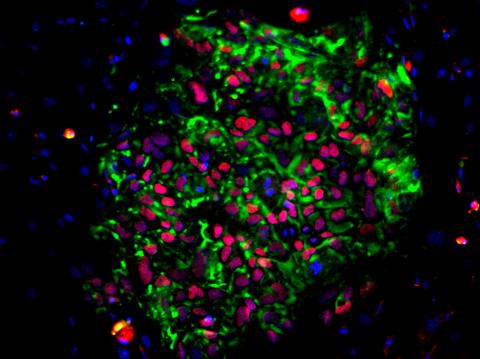

3278: Induced pluripotent stem cells from skin

3278: Induced pluripotent stem cells from skin

These induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) were derived from a woman's skin. Green and red indicate proteins found in reprogrammed cells but not in skin cells (TRA1-62 and NANOG). These cells can then develop into different cell types. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Related to image 3279.

Kathrin Plath lab, University of California, Los Angeles, via CIRM

View Media

2312: Color-coded chromosomes

2312: Color-coded chromosomes

By mixing fluorescent dyes like an artist mixes paints, scientists are able to color code individual chromosomes. The technique, abbreviated multicolor-FISH, allows researchers to visualize genetic abnormalities often linked to disease. In this image, "painted" chromosomes from a person with a hereditary disease called Werner Syndrome show where a piece of one chromosome has fused to another (see the gold-tipped maroon chromosome in the center). As reported by molecular biologist Jan Karlseder of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, such damage is typical among people with this rare syndrome.

Anna Jauch, Institute of Human Genetics, Heidelberg, Germany

View Media

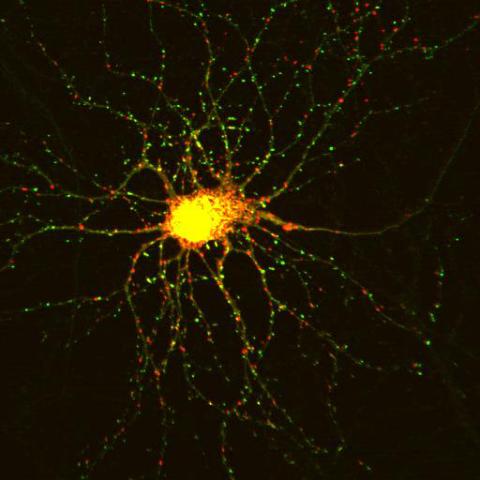

3509: Neuron with labeled synapses

3509: Neuron with labeled synapses

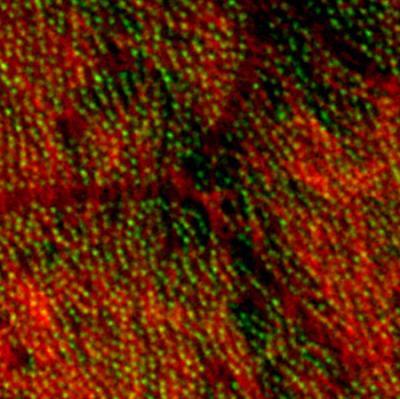

In this image, recombinant probes known as FingRs (Fibronectin Intrabodies Generated by mRNA display) were expressed in a cortical neuron, where they attached fluorescent proteins to either PSD95 (green) or Gephyrin (red). PSD-95 is a marker for synaptic strength at excitatory postsynaptic sites, and Gephyrin plays a similar role at inhibitory postsynaptic sites. Thus, using FingRs it is possible to obtain a map of synaptic connections onto a particular neuron in a living cell in real time.

Don Arnold and Richard Roberts, University of Southern California.

View Media

2437: Hydra 01

2437: Hydra 01

Hydra magnipapillata is an invertebrate animal used as a model organism to study developmental questions, for example the formation of the body axis.

Hiroshi Shimizu, National Institute of Genetics in Mishima, Japan

View Media

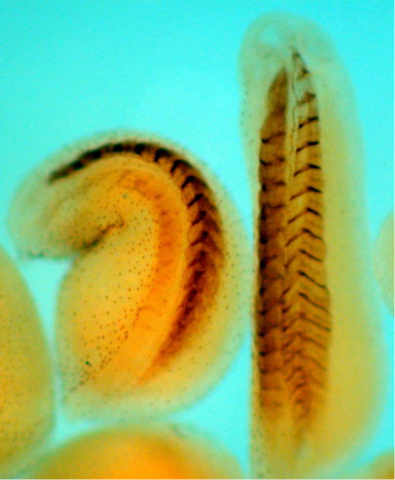

2756: Xenopus laevis embryos

2756: Xenopus laevis embryos

Xenopus laevis, the African clawed frog, has long been used as a model organism for studying embryonic development. The frog embryo on the left lacks the developmental factor Sizzled. A normal embryo is shown on the right.

Michael Klymkowsky, University of Colorado, Boulder

View Media

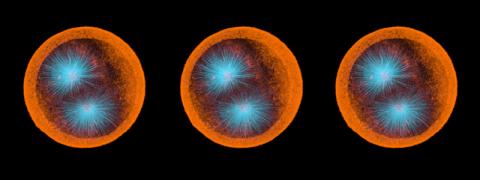

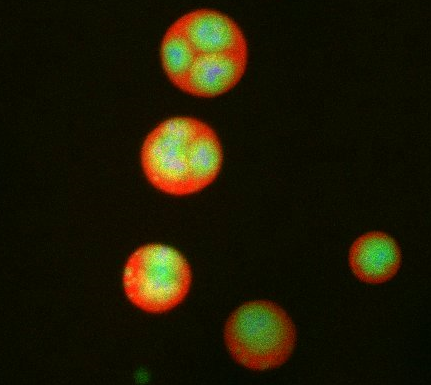

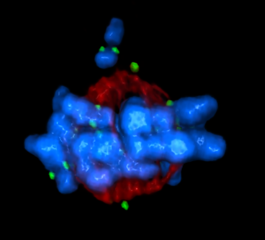

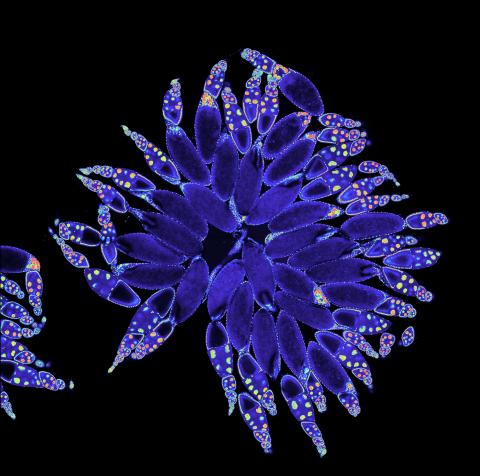

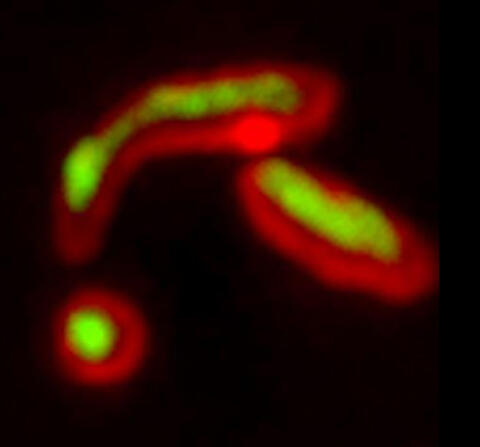

3792: Nucleolus subcompartments spontaneously self-assemble 3

3792: Nucleolus subcompartments spontaneously self-assemble 3

What looks a little like distant planets with some mysterious surface features are actually assemblies of proteins normally found in the cell's nucleolus, a small but very important protein complex located in the cell's nucleus. It forms on the chromosomes at the location where the genes for the RNAs are that make up the structure of the ribosome, the indispensable cellular machine that makes proteins from messenger RNAs.

However, how the nucleolus grows and maintains its structure has puzzled scientists for some time. It turns out that even though it looks like a simple liquid blob, it's rather well-organized, consisting of three distinct layers: the fibrillar center, where the RNA polymerase is active; the dense fibrillar component, which is enriched in the protein fibrillarin; and the granular component, which contains a protein called nucleophosmin. Researchers have now discovered that this multilayer structure of the nucleolus arises from differences in how the proteins in each compartment mix with water and with each other. These differences let the proteins readily separate from each other into the three nucleolus compartments.

This photo of nucleolus proteins in the eggs of a commonly used lab animal, the frog Xenopus laevis, shows each of the nucleolus compartments (the granular component is shown in red, the fibrillarin in yellow-green, and the fibrillar center in blue). The researchers have found that these compartments spontaneously fuse with each other on encounter without mixing with the other compartments.

For more details on this research, see this press release from Princeton. Related to video 3789, video 3791 and image 3793.

However, how the nucleolus grows and maintains its structure has puzzled scientists for some time. It turns out that even though it looks like a simple liquid blob, it's rather well-organized, consisting of three distinct layers: the fibrillar center, where the RNA polymerase is active; the dense fibrillar component, which is enriched in the protein fibrillarin; and the granular component, which contains a protein called nucleophosmin. Researchers have now discovered that this multilayer structure of the nucleolus arises from differences in how the proteins in each compartment mix with water and with each other. These differences let the proteins readily separate from each other into the three nucleolus compartments.

This photo of nucleolus proteins in the eggs of a commonly used lab animal, the frog Xenopus laevis, shows each of the nucleolus compartments (the granular component is shown in red, the fibrillarin in yellow-green, and the fibrillar center in blue). The researchers have found that these compartments spontaneously fuse with each other on encounter without mixing with the other compartments.

For more details on this research, see this press release from Princeton. Related to video 3789, video 3791 and image 3793.

Nilesh Vaidya, Princeton University

View Media

6966: Dying melanoma cells

6966: Dying melanoma cells

Melanoma (skin cancer) cells undergoing programmed cell death, also called apoptosis. This process was triggered by raising the pH of the medium that the cells were growing in. Melanoma in people cannot be treated by raising pH because that would also kill healthy cells. This video was taken using a differential interference contrast (DIC) microscope.

Dylan T. Burnette, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

View Media

2362: Automated crystal screening system

2362: Automated crystal screening system

Automated crystal screening systems such as the one shown here are becoming a common feature at synchrotron and other facilities where high-throughput crystal structure determination is being carried out. These systems rapidly screen samples to identify the best candidates for further study.

Southeast Collaboratory for Structural Genomics

View Media

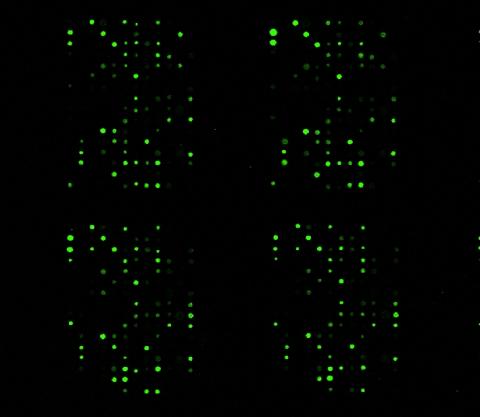

1265: Glycan arrays

1265: Glycan arrays

The signal is obtained by allowing proteins in human serum to interact with glycan (polysaccharide) arrays. The arrays are shown in replicate so the pattern is clear. Each spot contains a specific type of glycan. Proteins have bound to the spots highlighted in green.

Ola Blixt, Scripps Research Institute

View Media

2767: Research mentor and student

2767: Research mentor and student

A research mentor (Lori Eidson) and student (Nina Waldron, on the microscope) were 2009 members of the BRAIN (Behavioral Research Advancements In Neuroscience) program at Georgia State University in Atlanta. This program is an undergraduate summer research experience funded in part by NIGMS.

Elizabeth Weaver, Georgia State University

View Media

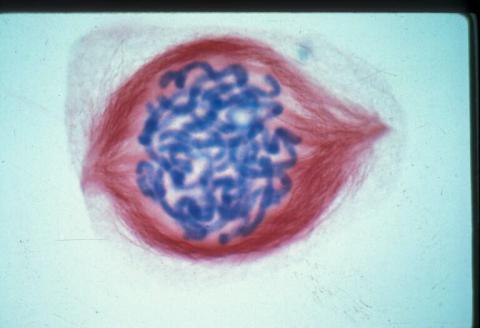

1015: Lily mitosis 05

1015: Lily mitosis 05

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, condensed chromosomes are clearly visible.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1016, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

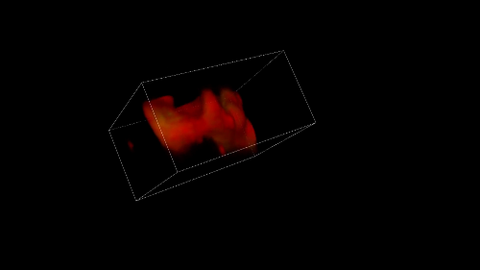

5877: Misfolded proteins in mitochondria, 3-D video

5877: Misfolded proteins in mitochondria, 3-D video

Three-dimensional image of misfolded proteins (green) within mitochondria (red). Related to image 5878. Learn more in this press release by The American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Rong Li, Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering, Johns Hopkins University

View Media

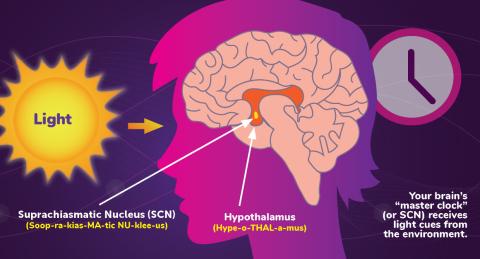

6613: Circadian rhythms and the SCN

6613: Circadian rhythms and the SCN

Circadian rhythms are physical, mental, and behavioral changes that follow a 24-hour cycle. Circadian rhythms are influenced by light and regulated by the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), sometimes referred to as a master clock. Learn more in NIGMS’ circadian rhythms fact sheet. See 6614 for the Spanish version of this infographic.

NIGMS

View Media

3788: Yeast cells pack a punch

3788: Yeast cells pack a punch

Although they are tiny, microbes that are growing in confined spaces can generate a lot of pressure. In this video, yeast cells grow in a small chamber called a microfluidic bioreactor. As the cells multiply, they begin to bump into and squeeze each other, resulting in periodic bursts of cells moving into different parts of the chamber. The continually growing cells also generate a lot of pressure--the researchers conducting these experiments found that the pressure generated by the cells can be almost five times higher than that in a car tire--about 150 psi, or 10 times the atmospheric pressure. Occasionally, this pressure even caused the small reactor to burst. By tracking the growth of the yeast or other cells and measuring the mechanical forces generated, scientists can simulate microbial growth in various places such as water pumps, sewage lines or catheters to learn how damage to these devices can be prevented. To learn more how researchers used small bioreactors to gauge the pressure generated by growing microbes, see this press release from UC Berkeley.

Oskar Hallatschek, UC Berkeley

View Media

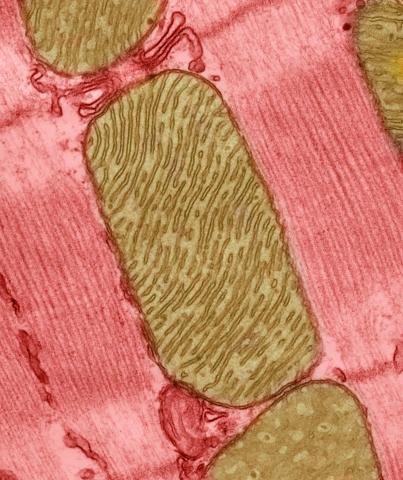

3664: Mitochondria from rat heart muscle cell_2

3664: Mitochondria from rat heart muscle cell_2

These mitochondria (brown) are from the heart muscle cell of a rat. Mitochondria have an inner membrane that folds in many places (and that appears here as striations). This folding vastly increases the surface area for energy production. Nearly all our cells have mitochondria. Related to image 3661.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research

View Media

6351: CRISPR

6351: CRISPR

RNA incorporated into the CRISPR surveillance complex is positioned to scan across foreign DNA. Cryo-EM density from a 3Å reconstruction is shown as a yellow mesh.

NRAMM National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy http://nramm.nysbc.org/nramm-images/ Source: Bridget Carragher

View Media

3594: Fly cells

3594: Fly cells

If a picture is worth a thousand words, what's a movie worth? For researchers studying cell migration, a "documentary" of fruit fly cells (bright green) traversing an egg chamber could answer longstanding questions about cell movement. See 2315 for video.

Denise Montell, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

View Media

7012: Adult Hawaiian bobtail squid burying in the sand

7012: Adult Hawaiian bobtail squid burying in the sand

Each morning, the nocturnal Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, hides from predators by digging into the sand. At dusk, it leaves the sand again to hunt.

Related to image 7010 and 7011.

Related to image 7010 and 7011.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

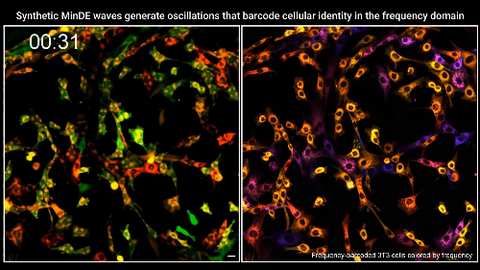

7022: Single-cell “radios” video

7022: Single-cell “radios” video

Individual cells are color-coded based on their identity and signaling activity using a protein circuit technology developed by the Coyle Lab. Just as a radio allows you to listen to an individual frequency, this technology allows researchers to tune into the specific “radio station” of each cell through genetically encoded proteins from a bacterial system called MinDE. The proteins generate an oscillating fluorescent signal that transmits information about cell shape, state, and identity that can be decoded using digital signal processing tools originally designed for telecommunications. The approach allows researchers to look at the dynamics of a single cell in the presence of many other cells.

Related to image 7021.

Related to image 7021.

Scott Coyle, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

View Media

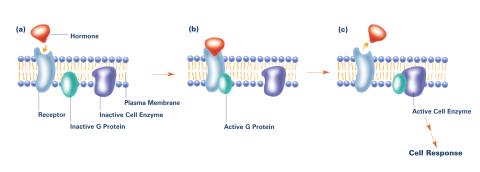

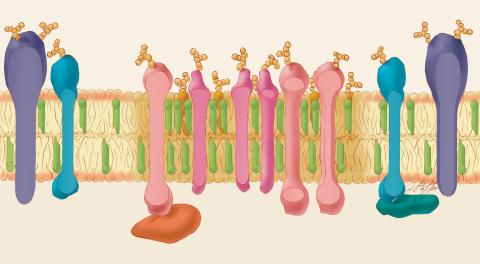

2538: G switch (with labels and stages)

2538: G switch (with labels and stages)

The G switch allows our bodies to respond rapidly to hormones. G proteins act like relay batons to pass messages from circulating hormones into cells. A hormone (red) encounters a receptor (blue) in the membrane of a cell. Next, a G protein (green) becomes activated and makes contact with the receptor to which the hormone is attached. Finally, the G protein passes the hormone's message to the cell by switching on a cell enzyme (purple) that triggers a response. See image 2536 and 2537 for other versions of this image. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

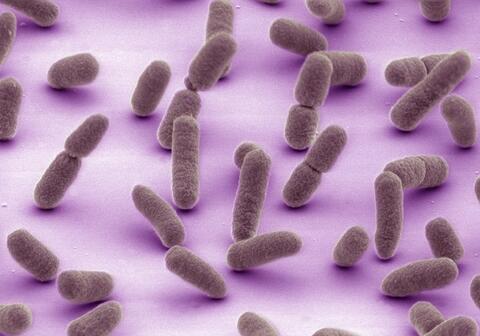

6850: Himastatin and bacteria

6850: Himastatin and bacteria

A model of the molecule himastatin overlaid on an image of Bacillus subtilis bacteria. Scientists first isolated himastatin from the bacterium Streptomyces himastatinicus, and the molecule shows antibiotic activity. The researchers who created this image developed a new, more concise way to synthesize himastatin so it can be studied more easily. They also tested the effects of himastatin and derivatives of the molecule on B. subtilis.

More information about the research that produced this image can be found in the Science paper “Total synthesis of himastatin” by D’Angelo et al.

Related to image 6848 and video 6851.

More information about the research that produced this image can be found in the Science paper “Total synthesis of himastatin” by D’Angelo et al.

Related to image 6848 and video 6851.

Mohammad Movassaghi, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Media

1120: Superconducting magnet

1120: Superconducting magnet

Superconducting magnet for NMR research, from the February 2003 profile of Dorothee Kern in Findings.

Mike Lovett

View Media

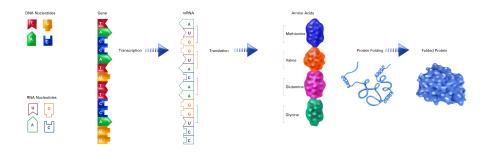

2510: From DNA to Protein (labeled)

2510: From DNA to Protein (labeled)

The genetic code in DNA is transcribed into RNA, which is translated into proteins with specific sequences. During transcription, nucleotides in DNA are copied into RNA, where they are read three at a time to encode the amino acids in a protein. Many parts of a protein fold as the amino acids are strung together.

See image 2509 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

See image 2509 for an unlabeled version of this illustration.

Featured in The Structures of Life.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

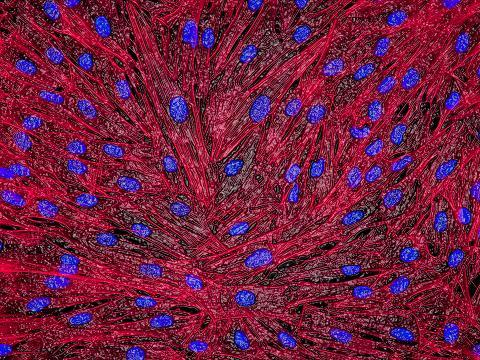

3670: DNA and actin in cultured fibroblast cells

3670: DNA and actin in cultured fibroblast cells

DNA (blue) and actin (red) in cultured fibroblast cells.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

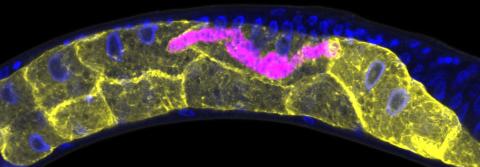

5777: Microsporidia in roundworm 1

5777: Microsporidia in roundworm 1

Many disease-causing microbes manipulate their host’s metabolism and cells for their own ends. Microsporidia—which are parasites closely related to fungi—infect and multiply inside animal cells, and take the rearranging of cells’ interiors to a new level. They reprogram animal cells such that the cells start to fuse, causing them to form long, continuous tubes. As shown in this image of the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, microsporidia (shown in magenta) have invaded the worm’s gut cells (shown in yellow; the cells’ nuclei are shown in blue) and have instructed the cells to merge. The cell fusion enables the microsporidia to thrive and propagate in the expanded space. Scientists study microsporidia in worms to gain more insight into how these parasites manipulate their host cells. This knowledge might help researchers devise strategies to prevent or treat infections with microsporidia. For more on the research into microsporidia, see this news release from the University of California San Diego. Related to images 5778 and 5779.

Keir Balla and Emily Troemel, University of California San Diego

View Media

1285: Lipid raft

1285: Lipid raft

Researchers have learned much of what they know about membranes by constructing artificial membranes in the laboratory. In artificial membranes, different lipids separate from each other based on their physical properties, forming small islands called lipid rafts.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

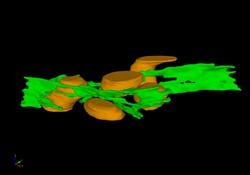

2635: Mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum

2635: Mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum

A computer model shows how the endoplasmic reticulum is close to and almost wraps around mitochondria in the cell. The endoplasmic reticulum is lime green and the mitochondria are yellow. This image relates to a July 27, 2009 article in Computing Life.

Bridget Wilson, University of New Mexico

View Media

5765: Mitotic cell awaits chromosome alignment

5765: Mitotic cell awaits chromosome alignment

During mitosis, spindle microtubules (red) attach to chromosome pairs (blue), directing them to the spindle equator. This midline alignment is critical for equal distribution of chromosomes in the dividing cell. Scientists are interested in how the protein kinase Plk1 (green) regulates this activity in human cells. Image is a volume projection of multiple deconvolved z-planes acquired with a Nikon widefield fluorescence microscope. This image was chosen as a winner of the 2016 NIH-funded research image call. Related to image 5766.

The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

View Media

The research that led to this image was funded by NIGMS.

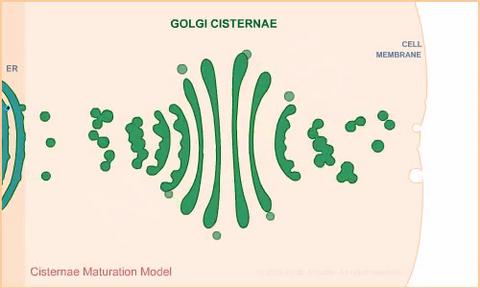

1307: Cisternae maturation model

1307: Cisternae maturation model

Animation for the cisternae maturation model of Golgi transport.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

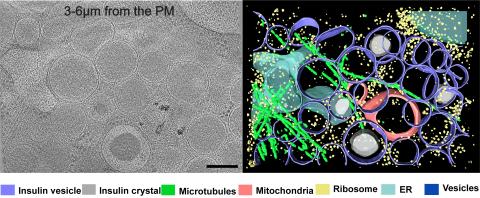

6607: Cryo-ET cell cross-section visualizing insulin vesicles

6607: Cryo-ET cell cross-section visualizing insulin vesicles

On the left, a cross-section slice of a rat pancreas cell captured using cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET). On the right, a color-coded, 3D version of the image highlighting cell structures. Visible features include insulin vesicles (purple rings), insulin crystals (gray circles), microtubules (green rods), ribosomes (small yellow circles). The black line at the bottom right of the left image represents 200 nm. Related to image 6608.

Xianjun Zhang, University of Southern California.

View Media

1081: Natcher Building 01

1081: Natcher Building 01

NIGMS staff are located in the Natcher Building on the NIH campus.

Alisa Machalek, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

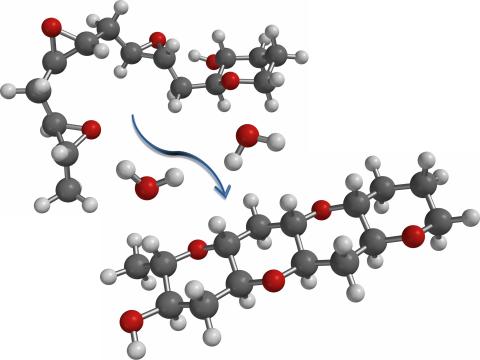

2490: Cascade reaction promoted by water

2490: Cascade reaction promoted by water

This illustration of an epoxide-opening cascade promoted by water emulates the proposed biosynthesis of some of the Red Tide toxins.

Tim Jamison, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

View Media

2802: Biosensors illustration

2802: Biosensors illustration

A rendering of an activity biosensor image overlaid with a cell-centered frame of reference used for image analysis of signal transduction. This is an example of NIH-supported research on single-cell analysis. Related to 2798 , 2799, 2800, 2801 and 2803.

Gaudenz Danuser, Harvard Medical School

View Media

5815: Introduction to Genome Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9

5815: Introduction to Genome Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9

Genome editing using CRISPR/Cas9 is a rapidly expanding field of scientific research with emerging applications in disease treatment, medical therapeutics and bioenergy, just to name a few. This technology is now being used in laboratories all over the world to enhance our understanding of how living biological systems work, how to improve treatments for genetic diseases and how to develop energy solutions for a better future.

Janet Iwasa

View Media

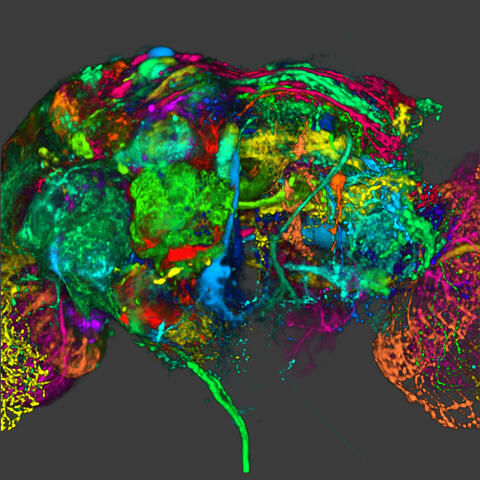

5838: Color coding of the Drosophila brain - image

5838: Color coding of the Drosophila brain - image

This image results from a research project to visualize which regions of the adult fruit fly (Drosophila) brain derive from each neural stem cell. First, researchers collected several thousand fruit fly larvae and fluorescently stained a random stem cell in the brain of each. The idea was to create a population of larvae in which each of the 100 or so neural stem cells was labeled at least once. When the larvae grew to adults, the researchers examined the flies’ brains using confocal microscopy. With this technique, the part of a fly’s brain that derived from a single, labeled stem cell “lights up. The scientists photographed each brain and digitally colorized its lit-up area. By combining thousands of such photos, they created a three-dimensional, color-coded map that shows which part of the Drosophila brain comes from each of its ~100 neural stem cells. In other words, each colored region shows which neurons are the progeny or “clones” of a single stem cell. This work established a hierarchical structure as well as nomenclature for the neurons in the Drosophila brain. Further research will relate functions to structures of the brain.

Related to image 5868 and video 5843

Related to image 5868 and video 5843

Yong Wan from Charles Hansen’s lab, University of Utah. Data preparation and visualization by Masayoshi Ito in the lab of Kei Ito, University of Tokyo.

View Media

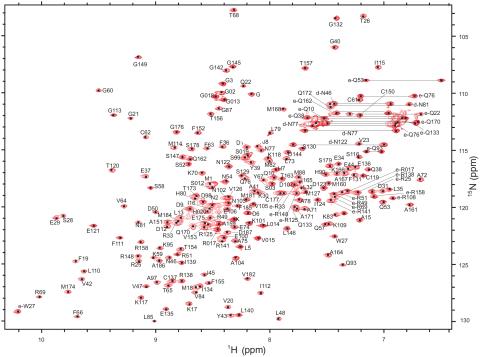

2299: 2-D NMR

2299: 2-D NMR

A two-dimensional NMR spectrum of a protein, in this case a 2D 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectrum of a 228 amino acid DNA/RNA-binding protein.

Dr. Xiaolian Gao's laboratory at the University of Houston

View Media

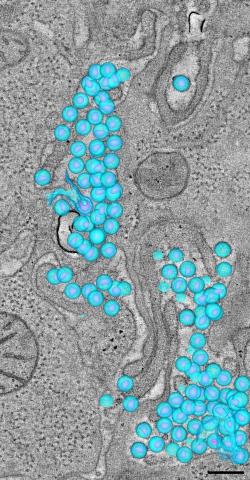

3571: HIV-1 virus in the colon

3571: HIV-1 virus in the colon

A tomographic reconstruction of the colon shows the location of large pools of HIV-1 virus particles (in blue) located in the spaces between adjacent cells. The purple objects within each sphere represent the conical cores that are one of the structural hallmarks of the HIV virus.

Mark Ladinsky, California Institute of Technology

View Media

2439: Hydra 03

2439: Hydra 03

Hydra magnipapillata is an invertebrate animal used as a model organism to study developmental questions, for example the formation of the body axis.

Hiroshi Shimizu, National Institute of Genetics in Mishima, Japan

View Media

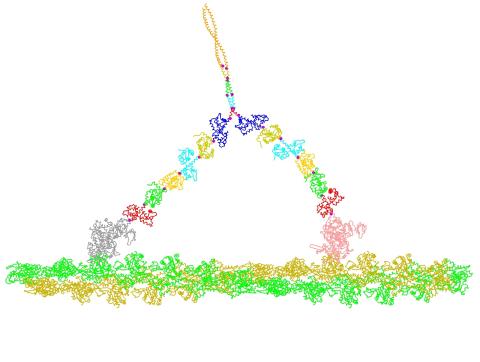

3786: Movie of in vitro assembly of a cell-signaling pathway

3786: Movie of in vitro assembly of a cell-signaling pathway

T cells are white blood cells that are important in defending the body against bacteria, viruses and other pathogens. Each T cell carries proteins, called T-cell receptors, on its surface that are activated when they come in contact with an invader. This activation sets in motion a cascade of biochemical changes inside the T cell to mount a defense against the invasion. Scientists have been interested for some time what happens after a T-cell receptor is activated. One obstacle has been to study how this signaling cascade, or pathway, proceeds inside T cells.

In this video, researchers have created a T-cell receptor pathway consisting of 12 proteins outside the cell on an artificial membrane. The video shows three key steps during the signaling process: phosphorylation of the T-cell receptor (green), clustering of a protein called linker for activation of T cells (LAT) (blue) and polymerization of the cytoskeleton protein actin (red). The findings show that the T-cell receptor signaling proteins self-organize into separate physical and biochemical compartments. This new system of studying molecular pathways outside the cells will enable scientists to better understand how the immune system combats microbes or other agents that cause infection.

To learn more how researchers assembled this T-cell receptor pathway, see this press release from HHMI's Marine Biological Laboratory Whitman Center. Related to image 3787.

In this video, researchers have created a T-cell receptor pathway consisting of 12 proteins outside the cell on an artificial membrane. The video shows three key steps during the signaling process: phosphorylation of the T-cell receptor (green), clustering of a protein called linker for activation of T cells (LAT) (blue) and polymerization of the cytoskeleton protein actin (red). The findings show that the T-cell receptor signaling proteins self-organize into separate physical and biochemical compartments. This new system of studying molecular pathways outside the cells will enable scientists to better understand how the immune system combats microbes or other agents that cause infection.

To learn more how researchers assembled this T-cell receptor pathway, see this press release from HHMI's Marine Biological Laboratory Whitman Center. Related to image 3787.

Xiaolei Su, HHMI Whitman Center of the Marine Biological Laboratory

View Media

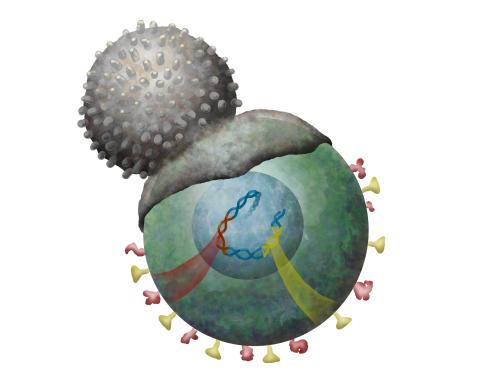

2489: Immune cell attacks cell infected with a retrovirus

2489: Immune cell attacks cell infected with a retrovirus

T cells engulf and digest cells displaying markers (or antigens) for retroviruses, such as HIV.

Kristy Whitehouse, science illustrator

View Media

3392: NCMIR Kidney Glomeruli

3392: NCMIR Kidney Glomeruli

Stained glomeruli in the kidney. The kidney is an essential organ responsible for disposing wastes from the body and for maintaining healthy ion levels in the blood. It works like a purifier by pulling break-down products of metabolism, such as urea and ammonium, from the bloodstream for excretion in urine. The glomerulus is a structure that helps filter the waste compounds from the blood. It consists of a network of capillaries enclosed within a Bowman's capsule of a nephron, which is the structure in which ions exit or re-enter the blood in the kidney.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

3607: Fruit fly ovary

3607: Fruit fly ovary

A fruit fly ovary, shown here, contains as many as 20 eggs. Fruit flies are not merely tiny insects that buzz around overripe fruit—they are a venerable scientific tool. Research on the flies has shed light on many aspects of human biology, including biological rhythms, learning, memory, and neurodegenerative diseases. Another reason fruit flies are so useful in a lab (and so successful in fruit bowls) is that they reproduce rapidly. About three generations can be studied in a single month.

Related to image 3656. This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Related to image 3656. This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Denise Montell, Johns Hopkins University and University of California, Santa Barbara

View Media

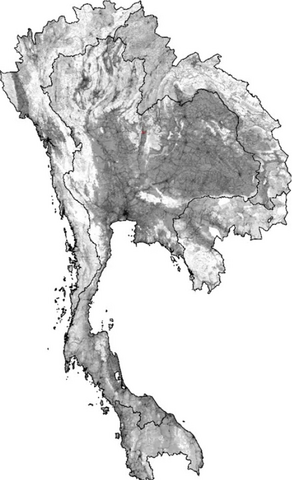

2574: Simulation of uncontrolled avian flu outbreak

2574: Simulation of uncontrolled avian flu outbreak

This video simulation shows what an uncontrolled outbreak of transmissible avian flu among people living in Thailand might look like. Red indicates new cases while green indicates areas where the epidemic has finished. The video shows the spread of infection and recovery over 300 days in Thailand and neighboring countries.

Neil M. Ferguson, Imperial College London

View Media

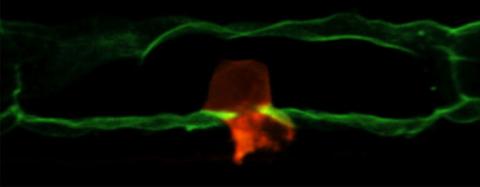

2707: Anchor cell in basement membrane

2707: Anchor cell in basement membrane

An anchor cell (red) pushes through the basement membrane (green) that surrounds it. Some cells are able to push through the tough basement barrier to carry out important tasks--and so can cancer cells, when they spread from one part of the body to another. No one has been able to recreate basement membranes in the lab and they're hard to study in humans, so Duke University researchers turned to the simple worm C. elegans. The researchers identified two molecules that help certain cells orient themselves toward and then punch through the worm's basement membrane. Studying these molecules and the genes that control them could deepen our understanding of cancer spread.

Elliott Hagedorn, Duke University.

View Media

3292: Centrioles anchor cilia in planaria

3292: Centrioles anchor cilia in planaria

Centrioles (green) anchor cilia (red), which project on the surface of pharynx cells of the freshwater planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. Centrioles require cellular structures called centrosomes for assembly in other animal species, but this flatworm known for its regenerative ability was unexpectedly found to lack centrosomes. From a Stowers University news release.

Juliette Azimzadeh, University of California, San Francisco

View Media

5878: Misfolded proteins within in the mitochondria

5878: Misfolded proteins within in the mitochondria

Misfolded proteins (green) within mitochondria (red). Related to video 5877.

Rong Li rong@jhu.edu Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Whiting School of Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218, USA.

View Media

2754: Myosin V binding to actin

2754: Myosin V binding to actin

This simulation of myosin V binding to actin was created using the software tool Protein Mechanica. With Protein Mechanica, researchers can construct models using information from a variety of sources: crystallography, cryo-EM, secondary structure descriptions, as well as user-defined solid shapes, such as spheres and cylinders. The goal is to enable experimentalists to quickly and easily simulate how different parts of a molecule interact.

Simbios, NIH Center for Biomedical Computation at Stanford

View Media