Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

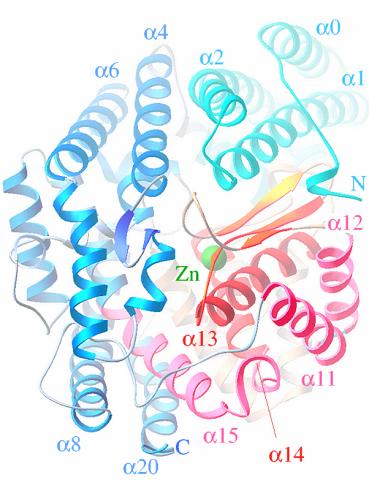

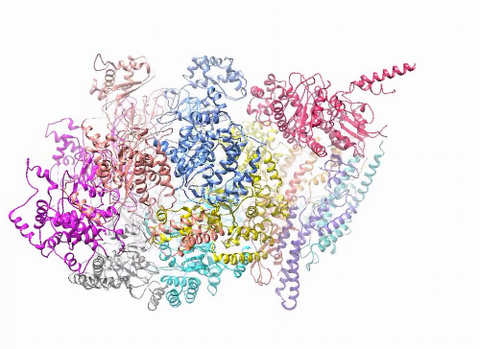

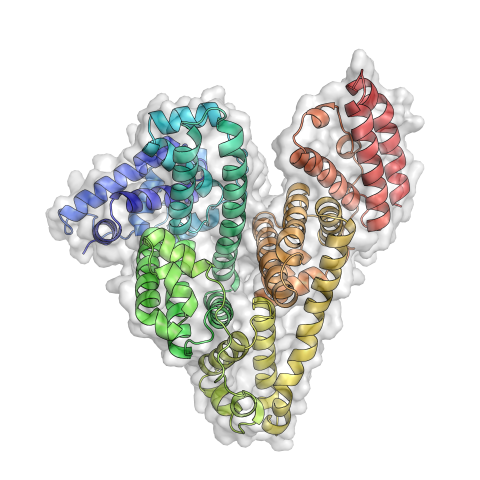

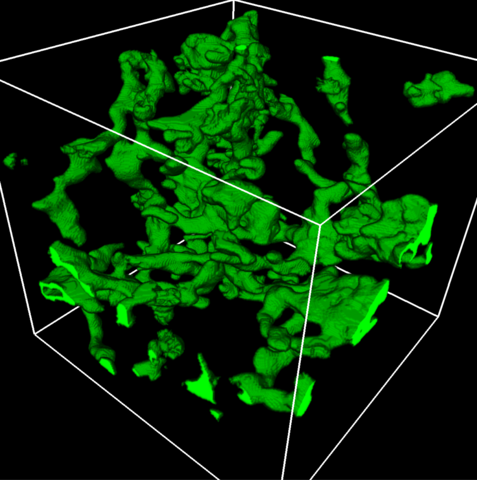

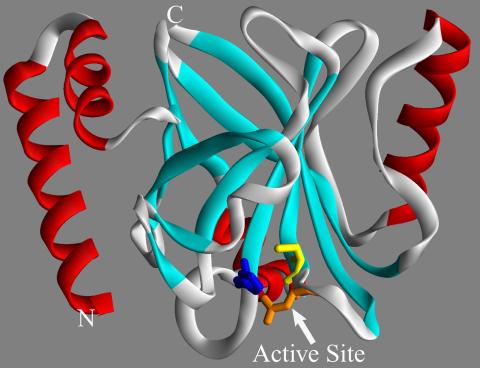

2373: Oligoendopeptidase F from B. stearothermophilus

2373: Oligoendopeptidase F from B. stearothermophilus

Crystal structure of oligoendopeptidase F, a protein slicing enzyme from Bacillus stearothermophilus, a bacterium that can cause food products to spoil. The crystal was formed using a microfluidic capillary, a device that enables scientists to independently control the parameters for protein crystal nucleation and growth. Featured as one of the July 2007 Protein Structure Initiative Structures of the Month.

Accelerated Technologies Center for Gene to 3D Structure/Midwest Center for Structural Genomics

View Media

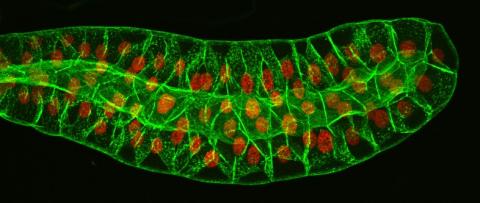

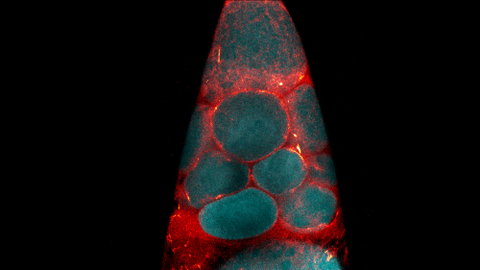

3603: Salivary gland in the developing fruit fly

3603: Salivary gland in the developing fruit fly

For fruit flies, the salivary gland is used to secrete materials for making the pupal case, the protective enclosure in which a larva transforms into an adult fly. For scientists, this gland provided one of the earliest glimpses into the genetic differences between individuals within a species. Chromosomes in the cells of these salivary glands replicate thousands of times without dividing, becoming so huge that scientists can easily view them under a microscope and see differences in genetic content between individuals.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Richard Fehon, University of Chicago

View Media

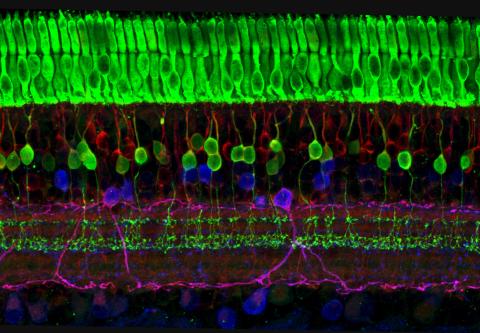

3635: The eye uses many layers of nerve cells to convert light into sight

3635: The eye uses many layers of nerve cells to convert light into sight

This image captures the many layers of nerve cells in the retina. The top layer (green) is made up of cells called photoreceptors that convert light into electrical signals to relay to the brain. The two best-known types of photoreceptor cells are rod- and cone-shaped. Rods help us see under low-light conditions but can't help us distinguish colors. Cones don't function well in the dark but allow us to see vibrant colors in daylight.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Wei Li, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health

View Media

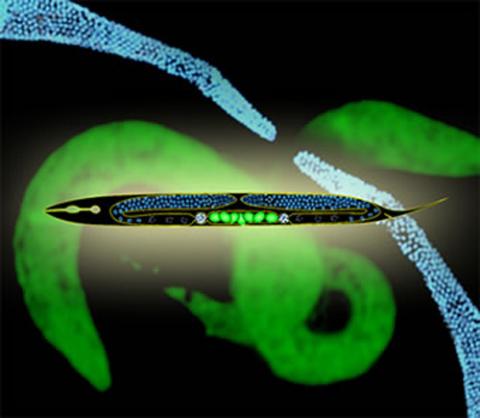

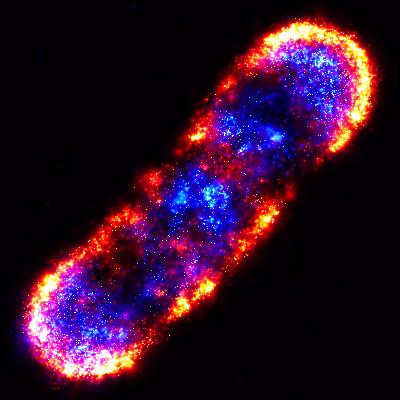

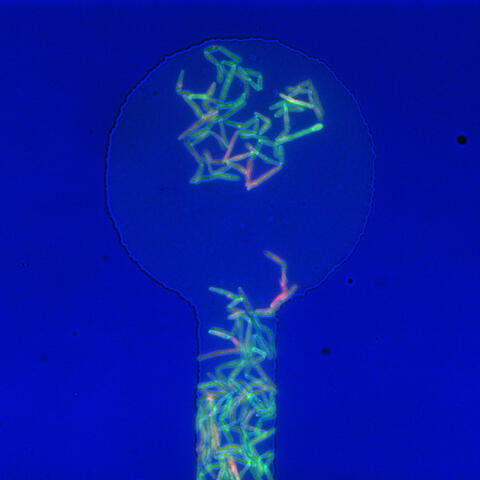

2333: Worms and human infertility

2333: Worms and human infertility

This montage of tiny, transparent C. elegans--or roundworms--may offer insight into understanding human infertility. Researchers used fluorescent dyes to label the worm cells and watch the process of sex cell division, called meiosis, unfold as nuclei (blue) move through the tube-like gonads. Such visualization helps the scientists identify mechanisms that enable these roundworms to reproduce successfully. Because meiosis is similar in all sexually reproducing organisms, what the scientists learn could apply to humans.

Abby Dernburg, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

View Media

2771: Self-organizing proteins

2771: Self-organizing proteins

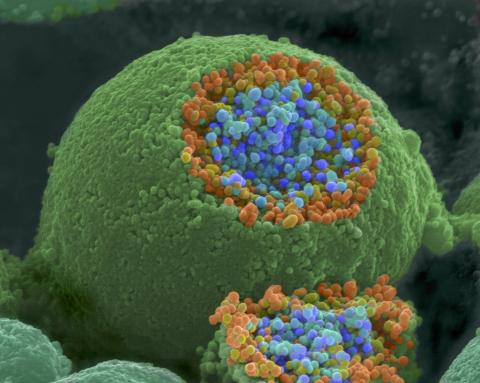

Under the microscope, an E. coli cell lights up like a fireball. Each bright dot marks a surface protein that tells the bacteria to move toward or away from nearby food and toxins. Using a new imaging technique, researchers can map the proteins one at a time and combine them into a single image. This lets them study patterns within and among protein clusters in bacterial cells, which don't have nuclei or organelles like plant and animal cells. Seeing how the proteins arrange themselves should help researchers better understand how cell signaling works.

View Media

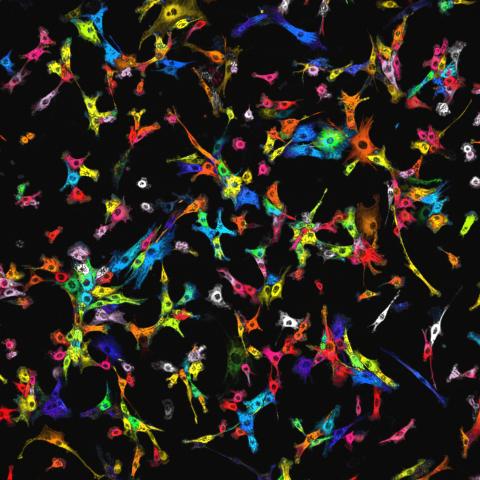

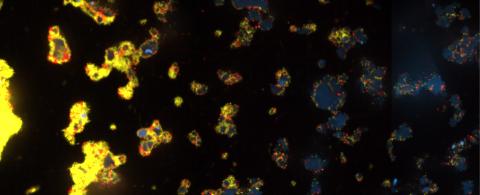

7021: Single-cell “radios” image

7021: Single-cell “radios” image

Individual cells are color-coded based on their identity and signaling activity using a protein circuit technology developed by the Coyle Lab. Just as a radio allows you to listen to an individual frequency, this technology allows researchers to tune into the specific “radio station” of each cell through genetically encoded proteins from a bacterial system called MinDE. The proteins generate an oscillating fluorescent signal that transmits information about cell shape, state, and identity that can be decoded using digital signal processing tools originally designed for telecommunications. The approach allows researchers to look at the dynamics of a single cell in the presence of many other cells.

Related to video 7022.

Related to video 7022.

Scott Coyle, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

View Media

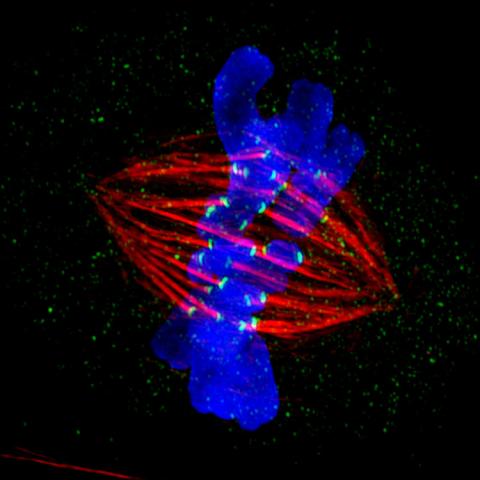

3445: Dividing cell in metaphase

3445: Dividing cell in metaphase

This image of a mammalian epithelial cell, captured in metaphase, was the winning image in the high- and super-resolution microscopy category of the 2012 GE Healthcare Life Sciences Cell Imaging Competition. The image shows microtubules (red), kinetochores (green) and DNA (blue). The DNA is fixed in the process of being moved along the microtubules that form the structure of the spindle.

The image was taken using the DeltaVision OMX imaging system, affectionately known as the "OMG" microscope, and was displayed on the NBC screen in New York's Times Square during the weekend of April 20-21, 2013. It was also part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

The image was taken using the DeltaVision OMX imaging system, affectionately known as the "OMG" microscope, and was displayed on the NBC screen in New York's Times Square during the weekend of April 20-21, 2013. It was also part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Jane Stout in the laboratory of Claire Walczak, Indiana University, GE Healthcare 2012 Cell Imaging Competition

View Media

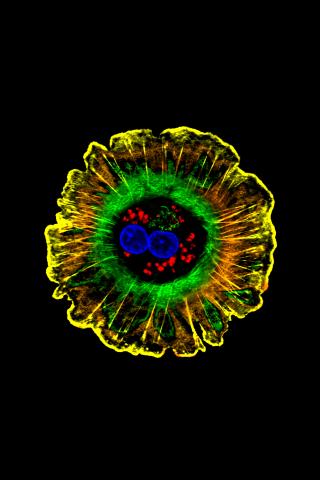

3610: Human liver cell (hepatocyte)

3610: Human liver cell (hepatocyte)

Hepatocytes, like the one shown here, are the most abundant type of cell in the human liver. They play an important role in building proteins; producing bile, a liquid that aids in digesting fats; and chemically processing molecules found normally in the body, like hormones, as well as foreign substances like medicines and alcohol.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Donna Beer Stolz, University of Pittsburgh

View Media

7012: Adult Hawaiian bobtail squid burying in the sand

7012: Adult Hawaiian bobtail squid burying in the sand

Each morning, the nocturnal Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, hides from predators by digging into the sand. At dusk, it leaves the sand again to hunt.

Related to image 7010 and 7011.

Related to image 7010 and 7011.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

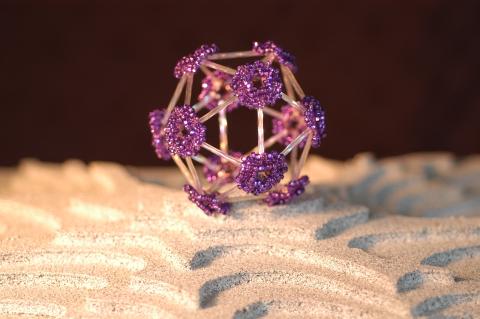

2305: Beaded bacteriophage

2305: Beaded bacteriophage

This sculpture made of purple and clear glass beads depicts bacteriophage Phi174, a virus that infects bacteria. It rests on a surface that portrays an adaptive landscape, a conceptual visualization. The ridges represent the gene combinations associated with the greatest fitness levels of the virus, as measured by how quickly the virus can reproduce itself. Phi174 is an important model system for studies of viral evolution because its genome can readily be sequenced as it evolves under defined laboratory conditions.

Holly Wichman, University of Idaho. (Surface by A. Johnston; photo by J. Palmersheim)

View Media

3580: V. Cholerae Biofilm

3580: V. Cholerae Biofilm

Industrious V. cholerae bacteria (yellow) tend to thrive in denser biofilms (left) while moochers (red) thrive in weaker biofilms (right). More information about the research behind this image can be found in a Biomedical Beat Blog posting from February 2014.

View Media

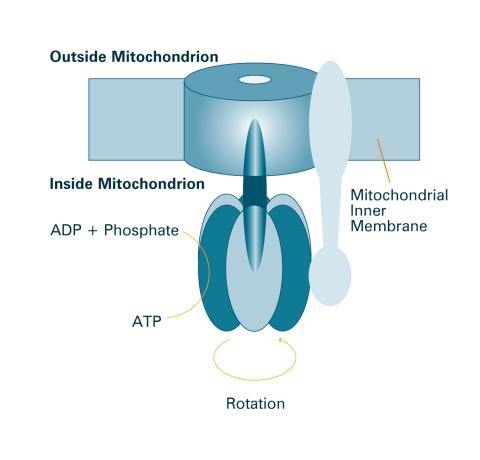

2518: ATP synthase (with labels)

2518: ATP synthase (with labels)

The world's smallest motor, ATP synthase, generates energy for the cell. See image 2517 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The Chemistry of Health.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

6538: Pathways: The Fascinating Cells of Research Organisms

6538: Pathways: The Fascinating Cells of Research Organisms

Learn how research organisms, such as fruit flies and mice, can help us understand and treat human diseases. Discover more resources from NIGMS’ Pathways collaboration with Scholastic. View the video on YouTube for closed captioning.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

1244: Nerve ending

1244: Nerve ending

A scanning electron microscope picture of a nerve ending. It has been broken open to reveal vesicles (orange and blue) containing chemicals used to pass messages in the nervous system.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

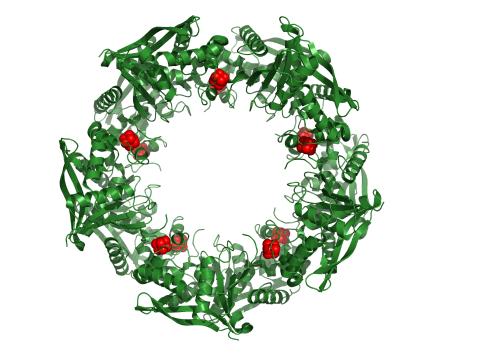

3720: Cas4 nuclease protein structure

3720: Cas4 nuclease protein structure

This wreath represents the molecular structure of a protein, Cas4, which is part of a system, known as CRISPR, that bacteria use to protect themselves against viral invaders. The green ribbons show the protein's structure, and the red balls show the location of iron and sulfur molecules important for the protein's function. Scientists harnessed Cas9, a different protein in the bacterial CRISPR system, to create a gene-editing tool known as CRISPR-Cas9. Using this tool, researchers are able to study a range of cellular processes and human diseases more easily, cheaply and precisely. In December, 2015, Science magazine recognized the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool as the "breakthrough of the year." Read more about Cas4 in the December 2015 Biomedical Beat post A Holiday-Themed Image Collection.

Fred Dyda, NIDDK

View Media

3487: Ion channel

3487: Ion channel

A special "messy" region of a potassium ion channel is important in its function.

Yu Zhoi, Christopher Lingle Laboratory, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis

View Media

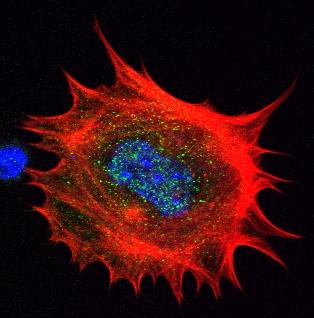

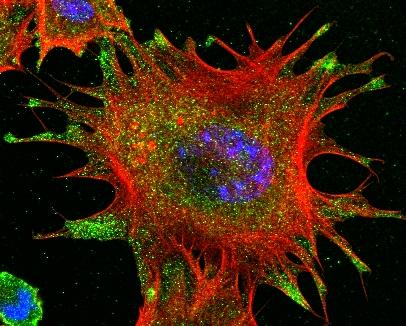

3329: Spreading Cells- 02

3329: Spreading Cells- 02

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3-/- fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red), Arp2 (green), and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). Arp2, a subunit of the Arp2/3 complex, is absent in the filopodi-like structures based leading edge of ARPC3-/- fibroblasts cells. Related to images 3328, 3330, 3331, 3332, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

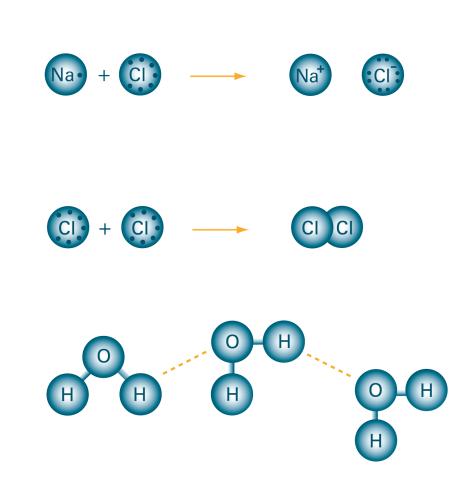

2519: Bond types

2519: Bond types

Ionic and covalent bonds hold molecules, like sodium chloride and chlorine gas, together. Hydrogen bonds among molecules, notably involving water, also play an important role in biology. See image 2520 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The Chemistry of Health.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

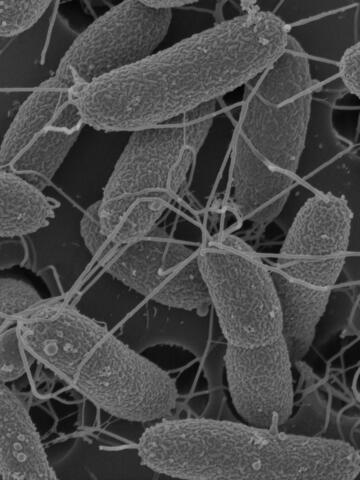

7014: Flagellated bacterial cells

7014: Flagellated bacterial cells

Vibrio fischeri (2 mm in length) is the exclusive symbiotic partner of the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes. After this bacterium uses its flagella to swim from the seawater into the light organ of a newly hatched juvenile, it colonizes the host and loses the appendages. This image was taken using a scanning electron microscope.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

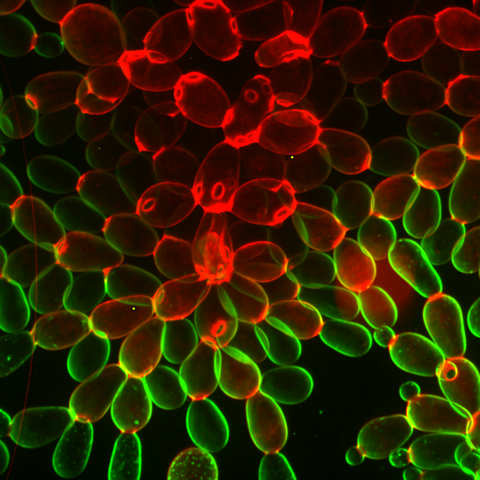

6969: Snowflake yeast 1

6969: Snowflake yeast 1

Multicellular yeast called snowflake yeast that researchers created through many generations of directed evolution from unicellular yeast. Stained cell membranes (green) and cell walls (red) reveal the connections between cells. Younger cells take up more cell membrane stain, while older cells take up more cell wall stain, leading to the color differences seen here. This image was captured using spinning disk confocal microscopy.

Related to images 6970 and 6971.

Related to images 6970 and 6971.

William Ratcliff, Georgia Institute of Technology.

View Media

5756: Pigment cells in fish skin

5756: Pigment cells in fish skin

Pigment cells are cells that give skin its color. In fishes and amphibians, like frogs and salamanders, pigment cells are responsible for the characteristic skin patterns that help these organisms to blend into their surroundings or attract mates. The pigment cells are derived from neural crest cells, which are cells originating from the neural tube in the early embryo. This image shows pigment cells from pearl danio, a relative of the popular laboratory animal zebrafish. Investigating pigment cell formation and migration in animals helps answer important fundamental questions about the factors that control pigmentation in the skin of animals, including humans. Related to images 5754, 5755, 5757 and 5758.

David Parichy, University of Washington

View Media

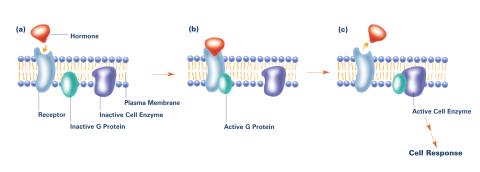

2538: G switch (with labels and stages)

2538: G switch (with labels and stages)

The G switch allows our bodies to respond rapidly to hormones. G proteins act like relay batons to pass messages from circulating hormones into cells. A hormone (red) encounters a receptor (blue) in the membrane of a cell. Next, a G protein (green) becomes activated and makes contact with the receptor to which the hormone is attached. Finally, the G protein passes the hormone's message to the cell by switching on a cell enzyme (purple) that triggers a response. See image 2536 and 2537 for other versions of this image. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2596: Sleep and the fly brain

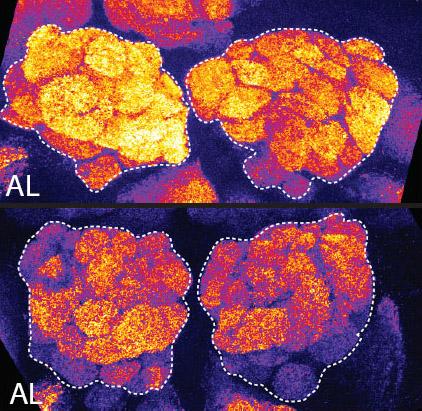

2596: Sleep and the fly brain

In the top snapshots, the brain of a sleep-deprived fruit fly glows orange, marking high concentrations of a synaptic protein called Bruchpilot (BRP) involved in communication between neurons. The color particularly lights up brain areas associated with learning. By contrast, the bottom images from a well-rested fly show lower levels of the protein. These pictures illustrate the results of an April 2009 study showing that sleep reduces the protein's levels, suggesting that such "downscaling" resets the brain to normal levels of synaptic activity and makes it ready to learn after a restful night.

Chiara Cirelli, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

3750: A dynamic model of the DNA helicase protein complex

3750: A dynamic model of the DNA helicase protein complex

This short video shows a model of the DNA helicase in yeast. This DNA helicase has 11 proteins that work together to unwind DNA during the process of copying it, called DNA replication. Scientists used a technique called cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which allowed them to study the helicase structure in solution rather than in static crystals. Cryo-EM in combination with computer modeling therefore allows researchers to see movements and other dynamic changes in the protein. The cryo-EM approach revealed the helicase structure at much greater resolution than could be obtained before. The researchers think that a repeated motion within the protein as shown in the video helps it move along the DNA strand. To read more about DNA helicase and this proposed mechanism, see this news release by Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Huilin Li, Stony Brook University

View Media

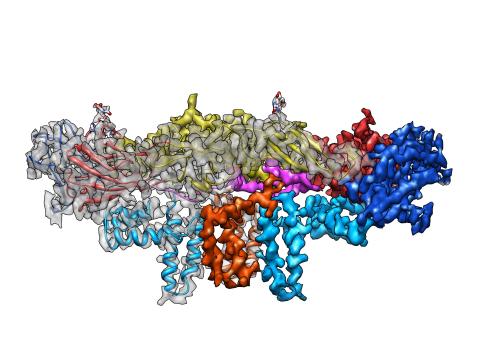

3758: Dengue virus membrane protein structure

3758: Dengue virus membrane protein structure

Dengue virus is a mosquito-borne illness that infects millions of people in the tropics and subtropics each year. Like many viruses, dengue is enclosed by a protective membrane. The proteins that span this membrane play an important role in the life cycle of the virus. Scientists used cryo-EM to determine the structure of a dengue virus at a 3.5-angstrom resolution to reveal how the membrane proteins undergo major structural changes as the virus matures and infects a host. The image shows a side view of the structure of a protein composed of two smaller proteins, called E and M. Each E and M contributes two molecules to the overall protein structure (called a heterotetramer), which is important for assembling and holding together the viral membrane, i.e., the shell that surrounds the genetic material of the dengue virus. The dengue protein's structure has revealed some portions in the protein that might be good targets for developing medications that could be used to combat dengue virus infections. For more on cryo-EM see the blog post Cryo-Electron Microscopy Reveals Molecules in Ever Greater Detail. You can watch a rotating view of the dengue virus surface structure in video 3748.

Hong Zhou, UCLA

View Media

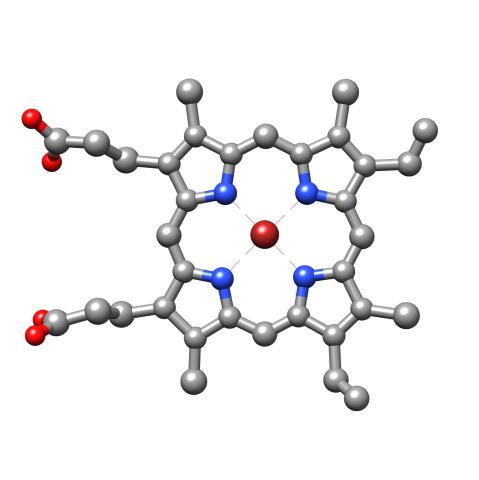

3539: Structure of heme, top view

3539: Structure of heme, top view

Molecular model of the struture of heme. Heme is a small, flat molecule with an iron ion (dark red) at its center. Heme is an essential component of hemoglobin, the protein in blood that carries oxygen throughout our bodies. This image first appeared in the September 2013 issue of Findings Magazine. View side view of heme here 3540.

Rachel Kramer Green, RCSB Protein Data Bank

View Media

1191: Mouse sperm sections

1191: Mouse sperm sections

This transmission electron micrograph shows sections of mouse sperm tails, or flagella.

Tina Weatherby Carvalho, University of Hawaii at Manoa

View Media

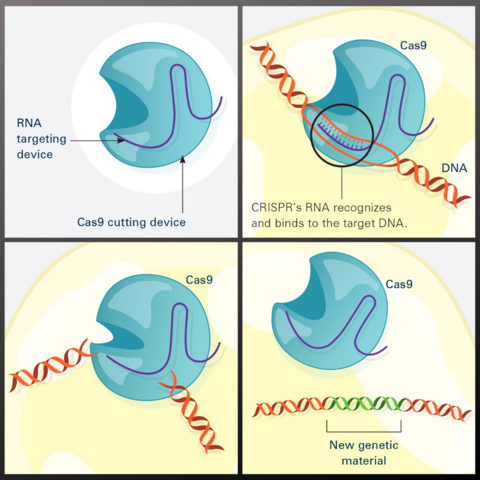

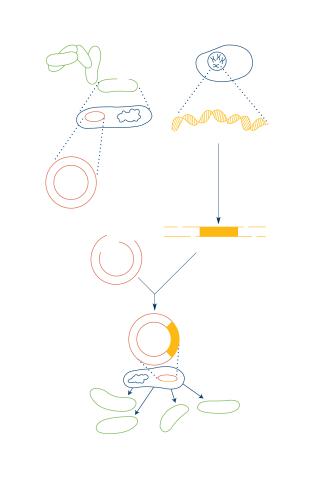

7036: CRISPR Illustration

7036: CRISPR Illustration

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool.

Frame 1 shows the two components of the CRISPR system: a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA), and a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence).

In frame 2, the CRISPR machine locates the target DNA sequence once inserted into a cell.

In frame 3, the Cas9 enzyme cuts both strands of the DNA.

Frame 4 shows a repaired DNA strand with new genetic material that researchers can introduce, which the cell automatically incorporates into the gap when it repairs the broken DNA.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video.

Download the individual frames: Frame 1, Frame 2, Frame 3, and Frame 4.

Frame 1 shows the two components of the CRISPR system: a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA), and a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence).

In frame 2, the CRISPR machine locates the target DNA sequence once inserted into a cell.

In frame 3, the Cas9 enzyme cuts both strands of the DNA.

Frame 4 shows a repaired DNA strand with new genetic material that researchers can introduce, which the cell automatically incorporates into the gap when it repairs the broken DNA.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video.

Download the individual frames: Frame 1, Frame 2, Frame 3, and Frame 4.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

2407: Jack bean concanavalin A

2407: Jack bean concanavalin A

Crystals of jack bean concanavalin A protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

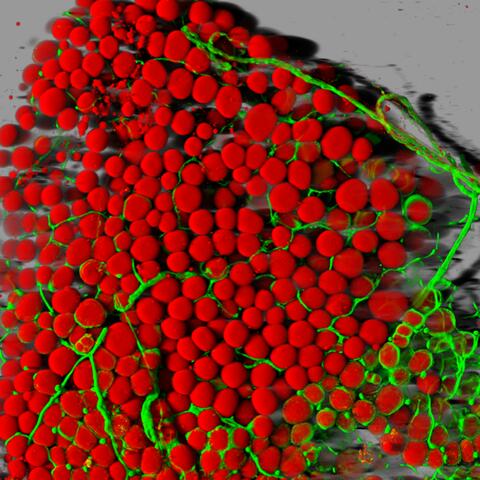

3600: Fat cells (red) and blood vessels (green)

3600: Fat cells (red) and blood vessels (green)

A mouse's fat cells (red) are shown surrounded by a network of blood vessels (green). Fat cells store and release energy, protect organs and nerve tissues, insulate us from the cold, and help us absorb important vitamins.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Daniela Malide, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health

View Media

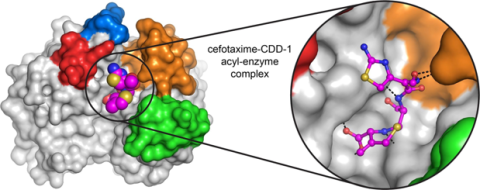

6767: Space-filling model of a cefotaxime-CCD-1 complex

6767: Space-filling model of a cefotaxime-CCD-1 complex

CCD-1 is an enzyme produced by the bacterium Clostridioides difficile that helps it resist antibiotics. Using X-ray crystallography, researchers determined the structure of a complex between CCD-1 and the antibiotic cefotaxime (purple, yellow, and blue molecule). The structure revealed that CCD-1 provides extensive hydrogen bonding (shown as dotted lines) and stabilization of the antibiotic in the active site, leading to efficient degradation of the antibiotic.

Related to images 6764, 6765, and 6766.

Related to images 6764, 6765, and 6766.

Keith Hodgson, Stanford University.

View Media

3526: 800 MHz NMR magnet

3526: 800 MHz NMR magnet

Scientists use nuclear magnetic spectroscopy (NMR) to determine the detailed, 3D structures of molecules.

Asokan Anbanandam, University of Kansas

View Media

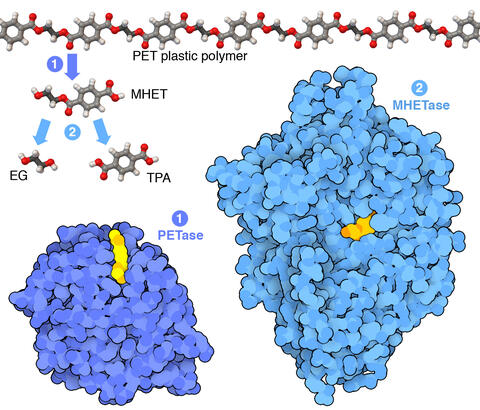

7000: Plastic-eating enzymes

7000: Plastic-eating enzymes

PETase enzyme degrades polyester plastic (polyethylene terephthalate, or PET) into monohydroxyethyl terephthalate (MHET). Then, MHETase enzyme degrades MHET into its constituents ethylene glycol (EG) and terephthalic acid (TPA).

Find these in the RCSB Protein Data Bank: PET hydrolase (PDB entry 5XH3) and MHETase (PDB entry 6QGA).

Find these in the RCSB Protein Data Bank: PET hydrolase (PDB entry 5XH3) and MHETase (PDB entry 6QGA).

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

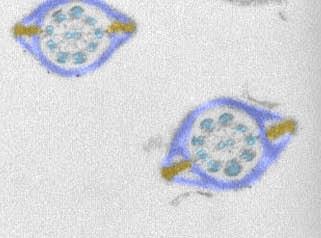

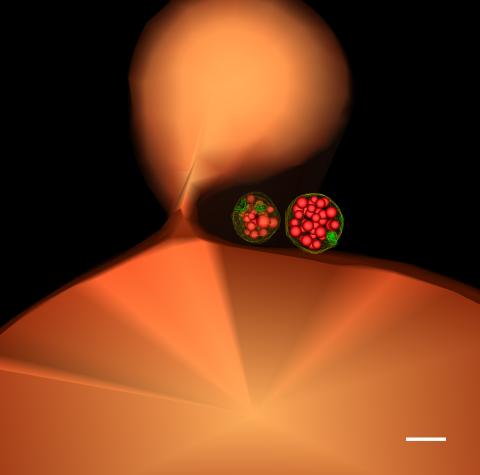

5769: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 1

5769: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 1

Collecting and transporting cellular waste and sorting it into recylable and nonrecylable pieces is a complex business in the cell. One key player in that process is the endosome, which helps collect, sort and transport worn-out or leftover proteins with the help of a protein assembly called the endosomal sorting complexes for transport (or ESCRT for short). These complexes help package proteins marked for breakdown into intralumenal vesicles, which, in turn, are enclosed in multivesicular bodies for transport to the places where the proteins are recycled or dumped. In this image, two multivesicular bodies (with yellow membranes) contain tiny intralumenal vesicles (with a diameter of only 25 nanometers; shown in red) adjacent to the cell's vacuole (in orange).

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a microscopy photograph 5768 that was used to generate this illustration and a zoomed-in version 5767 of this illustration.

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a microscopy photograph 5768 that was used to generate this illustration and a zoomed-in version 5767 of this illustration.

Matthew West and Greg Odorizzi, University of Colorado

View Media

3746: Serum albumin structure 3

3746: Serum albumin structure 3

Serum albumin (SA) is the most abundant protein in the blood plasma of mammals. SA has a characteristic heart-shape structure and is a highly versatile protein. It helps maintain normal water levels in our tissues and carries almost half of all calcium ions in human blood. SA also transports some hormones, nutrients and metals throughout the bloodstream. Despite being very similar to our own SA, those from other animals can cause some mild allergies in people. Therefore, some scientists study SAs from humans and other mammals to learn more about what subtle structural or other differences cause immune responses in the body.

Related to entries 3744 and 3745.

Related to entries 3744 and 3745.

Wladek Minor, University of Virginia

View Media

6754: Fruit fly nurse cells transporting their contents during egg development

6754: Fruit fly nurse cells transporting their contents during egg development

In many animals, the egg cell develops alongside sister cells. These sister cells are called nurse cells in the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), and their job is to “nurse” an immature egg cell, or oocyte. Toward the end of oocyte development, the nurse cells transfer all their contents into the oocyte in a process called nurse cell dumping. This video captures this transfer, showing significant shape changes on the part of the nurse cells (blue), which are powered by wavelike activity of the protein myosin (red). Researchers created the video using a confocal laser scanning microscope. Related to image 6753.

Adam C. Martin, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Media

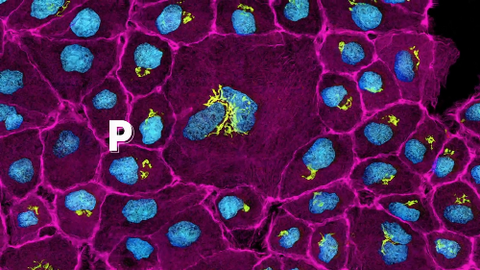

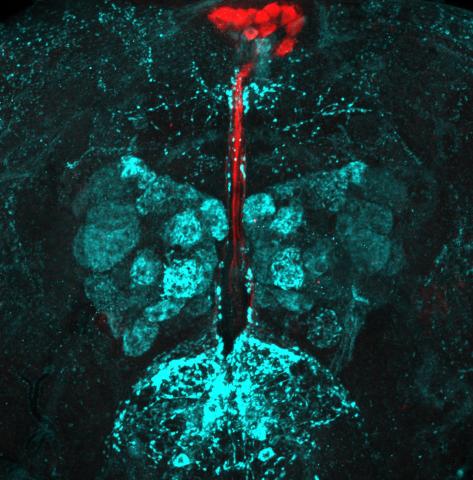

6985: Fruit fly brain responds to adipokines

6985: Fruit fly brain responds to adipokines

Drosophila adult brain showing that an adipokine (fat hormone) generates a response from neurons (aqua) and regulates insulin-producing neurons (red).

Related to images 6982, 6983, and 6984.

Related to images 6982, 6983, and 6984.

Akhila Rajan, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center

View Media

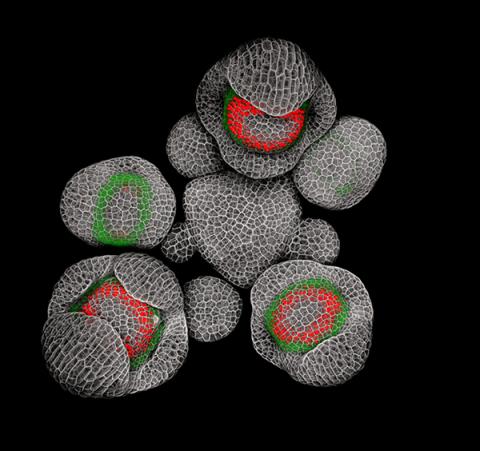

3743: Developing Arabidopsis flower buds

3743: Developing Arabidopsis flower buds

Flower development is a carefully orchestrated, genetically programmed process that ensures that the male (stamen) and female (pistil) organs form in the right place and at the right time in the flower. In this image of young Arabidopsis flower buds, the gene SUPERMAN (red) is activated at the boundary between the cells destined to form the male and female parts. SUPERMAN activity prevents the central cells, which will ultimately become the female pistil, from activating the gene APETALA3 (green), which induces formation of male flower organs. The goal of this research is to find out how plants maintain cells (called stem cells) that have the potential to develop into any type of cell and how genetic and environmental factors cause stem cells to develop and specialize into different cell types. This work informs future studies in agriculture, medicine and other fields.

Nathanaël Prunet, Caltech

View Media

2564: Recombinant DNA

2564: Recombinant DNA

To splice a human gene into a plasmid, scientists take the plasmid out of an E. coli bacterium, cut the plasmid with a restriction enzyme, and splice in human DNA. The resulting hybrid plasmid can be inserted into another E. coli bacterium, where it multiplies along with the bacterium. There, it can produce large quantities of human protein. See image 2565 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

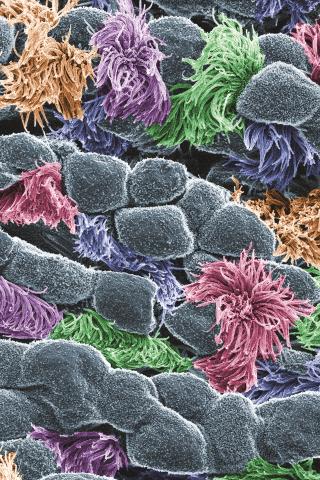

3646: Cells lining the trachea

3646: Cells lining the trachea

In this image, viewed with a ZEISS ORION NanoFab microscope, the community of cells lining a mouse airway is magnified more than 10,000 times. This collection of cells, known as the mucociliary escalator, is also found in humans. It is our first line of defense against inhaled bacteria, allergens, pollutants, and debris. Malfunctions in the system can cause or aggravate lung infections and conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The cells shown in gray secrete mucus, which traps inhaled particles. The colored cells sweep the mucus layer out of the lungs.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Eva Mutunga and Kate Klein, University of the District of Columbia and National Institute of Standards and Technology

View Media

5857: 3D reconstruction of a tubular matrix in peripheral endoplasmic reticulum

5857: 3D reconstruction of a tubular matrix in peripheral endoplasmic reticulum

Detailed three-dimensional reconstruction of a tubular matrix in a thin section of the peripheral endoplasmic reticulum between the plasma membranes of the cell. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a continuous membrane that extends like a net from the envelope of the nucleus outward to the cell membrane. The ER plays several roles within the cell, such as in protein and lipid synthesis and transport of materials between organelles. Shown here is a three-dimensional representation of the peripheral ER microtubules. Related to images 5855 and 5856

Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, Howard Hughes Medical Institute Janelia Research Campus, Virginia

View Media

2386: Sortase b from B. anthracis

2386: Sortase b from B. anthracis

Structure of sortase b from the bacterium B. anthracis, which causes anthrax. Sortase b is an enzyme used to rob red blood cells of iron, which the bacteria need to survive.

Midwest Center for Structural Genomics, PSI

View Media

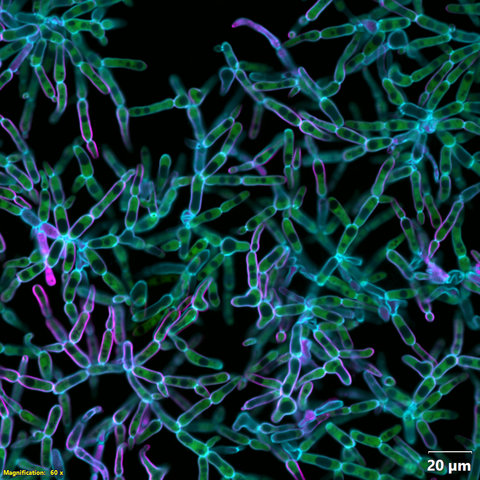

5751: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 1

5751: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 1

Antibiotic resistance in microbes is a serious health concern. So researchers have turned their attention to how bacteria undo the action of some antibiotics. Here, scientists set out to find the conditions that help individual bacterial cells survive in the presence of the antibiotic rifampicin. The research team used Mycobacterium smegmatis, a more harmless relative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which infects the lung and other organs and causes serious disease.

In this image, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to video 5752.

In this image, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to video 5752.

Bree Aldridge, Tufts University

View Media

6970: Snowflake yeast 2

6970: Snowflake yeast 2

Multicellular yeast called snowflake yeast that researchers created through many generations of directed evolution from unicellular yeast. Cells are connected to one another by their cell walls, shown in blue. Stained cytoplasm (green) and membranes (magenta) show that the individual cells remain separate. This image was captured using spinning disk confocal microscopy.

Related to images 6969 and 6971.

Related to images 6969 and 6971.

William Ratcliff, Georgia Institute of Technology.

View Media

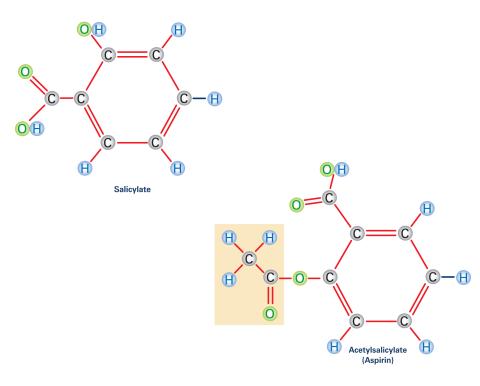

2530: Aspirin (with labels)

2530: Aspirin (with labels)

Acetylsalicylate (bottom) is the aspirin of today. Adding a chemical tag called an acetyl group (shaded box, bottom) to a molecule derived from willow bark (salicylate, top) makes the molecule less acidic (and easier on the lining of the digestive tract), but still effective at relieving pain. See image 2529 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

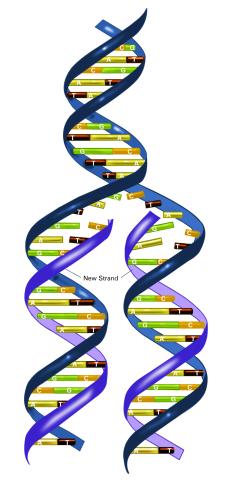

2544: DNA replication illustration (with labels)

2544: DNA replication illustration (with labels)

During DNA replication, each strand of the original molecule acts as a template for the synthesis of a new, complementary DNA strand. See image 2543 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

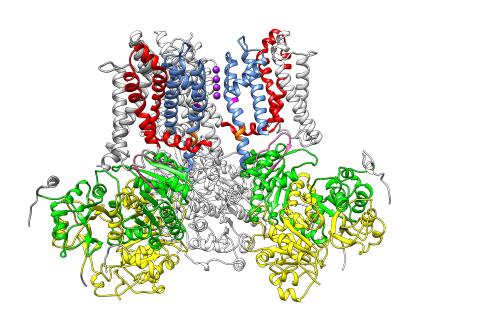

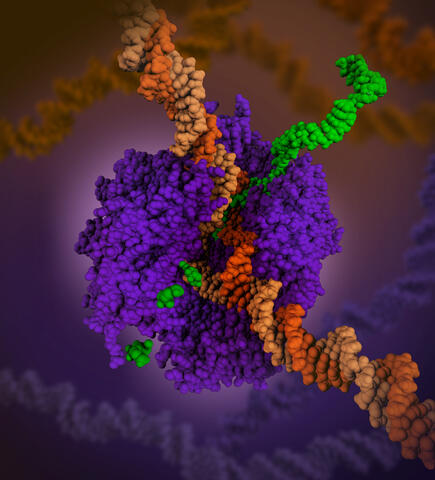

6993: RNA polymerase

6993: RNA polymerase

RNA polymerase (purple) is a complex enzyme at the heart of transcription. During this process, the enzyme unwinds the DNA double helix and uses one strand (darker orange) as a template to create the single-stranded messenger RNA (green), later used by ribosomes for protein synthesis.

From the RNA polymerase II elongation complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PDB entry 1I6H) as seen in PDB-101's What is a Protein? video.

From the RNA polymerase II elongation complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PDB entry 1I6H) as seen in PDB-101's What is a Protein? video.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

3331: mDia1 antibody staining- 02

3331: mDia1 antibody staining- 02

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3-/- fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red), mDia1 (green), and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). In ARPC3-/- fibroblast cells, mDia1 is localized at the tips of the filopodia-like structures. Related to images 3328, 3329, 3330, 3332, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media

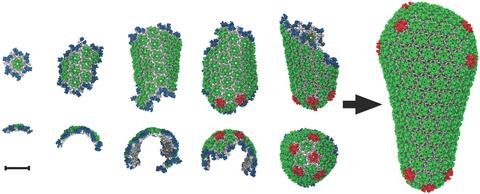

5729: Assembly of the HIV capsid

5729: Assembly of the HIV capsid

The HIV capsid is a pear-shaped structure that is made of proteins the virus needs to mature and become infective. The capsid is inside the virus and delivers the virus' genetic information into a human cell. To better understand how the HIV capsid does this feat, scientists have used computer programs to simulate its assembly. This image shows a series of snapshots of the steps that grow the HIV capsid. A model of a complete capsid is shown on the far right of the image for comparison; the green, blue and red colors indicate different configurations of the capsid protein that make up the capsid “shell.” The bar in the left corner represents a length of 20 nanometers, which is less than a tenth the size of the smallest bacterium. Computer models like this also may be used to reconstruct the assembly of the capsids of other important viruses, such as Ebola or the Zika virus. The studies reporting this research were published in Nature Communications and Nature. To learn more about how researchers used computer simulations to track the assembly of the HIV capsid, see this press release from the University of Chicago.

John Grime and Gregory Voth, The University of Chicago

View Media

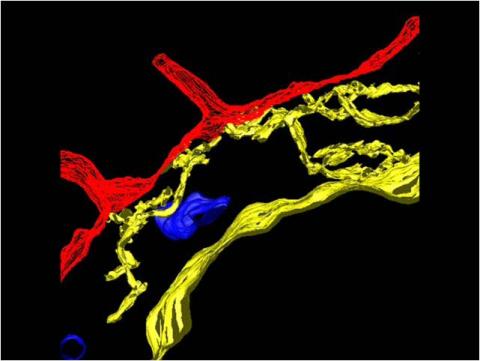

2636: Computer model of cell membrane

2636: Computer model of cell membrane

A computer model of the cell membrane, where the plasma membrane is red, endoplasmic reticulum is yellow, and mitochondria are blue. This image relates to a July 27, 2009 article in Computing Life.

Bridget Wilson, University of New Mexico

View Media