Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

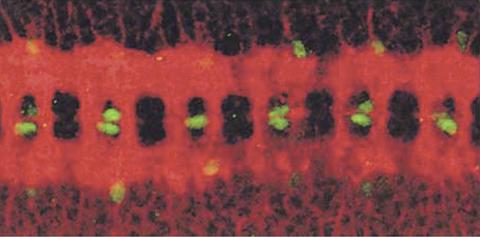

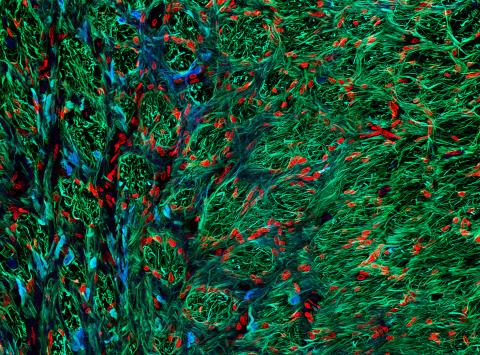

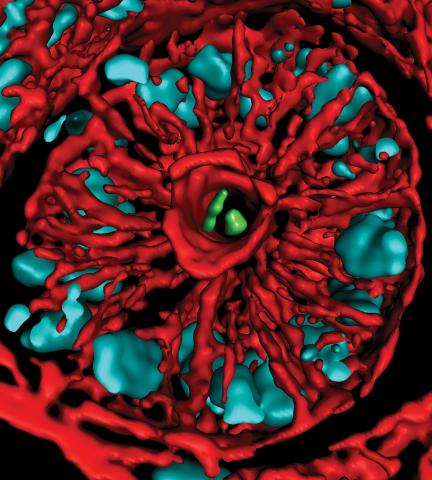

1091: Nerve and glial cells in fruit fly embryo

1091: Nerve and glial cells in fruit fly embryo

Glial cells (stained green) in a fruit fly developing embryo have survived thanks to a signaling pathway initiated by neighboring nerve cells (stained red).

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

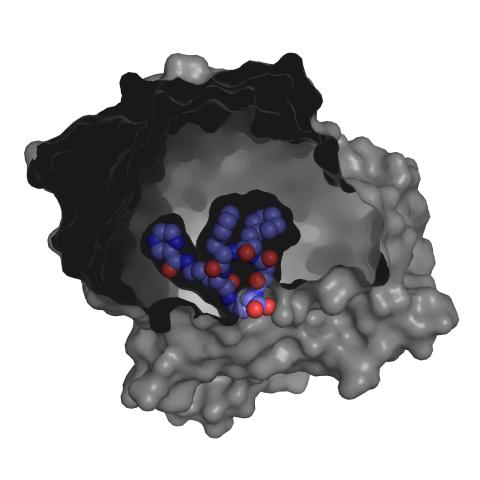

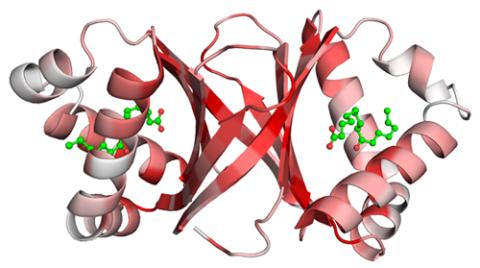

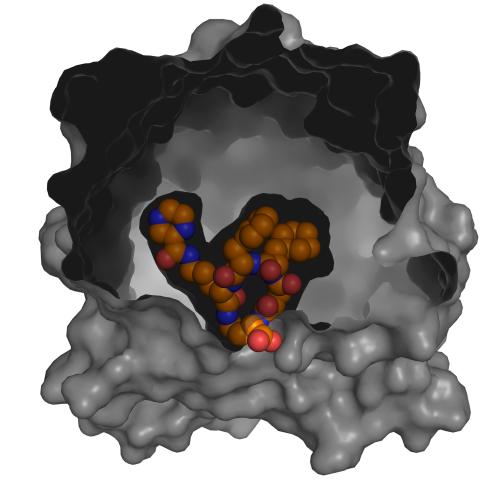

3415: X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor 3

3415: X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor 3

X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor. Related to 3413, 3414, 3416, 3417, 3418, and 3419.

Markus A. Seeliger, Stony Brook University Medical School and David R. Liu, Harvard University

View Media

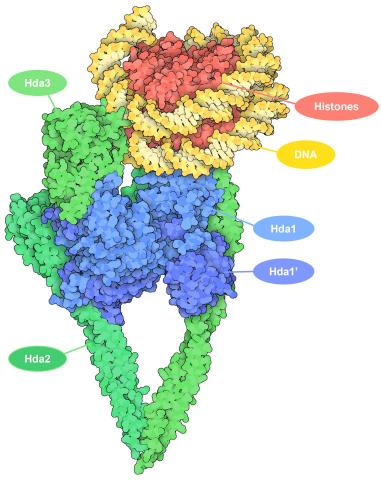

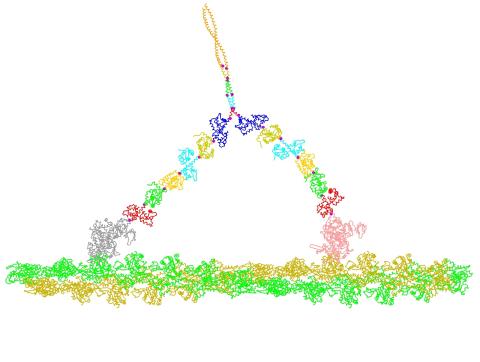

7001: Histone deacetylases

7001: Histone deacetylases

The human genome contains much of the information needed for every cell in the body to function. However, different types of cells often need different types of information. Access to DNA is controlled, in part, by how tightly it’s wrapped around proteins called histones to form nucleosomes. The complex shown here, from yeast cells (PDB entry 6Z6P), includes several histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes (green and blue) bound to a nucleosome (histone proteins in red; DNA in yellow). The yeast HDAC enzymes are similar to the human enzymes. Two enzymes form a V-shaped clamp (green) that holds the other others, a dimer of the Hda1 enzymes (blue). In this assembly, Hda1 is activated and positioned to remove acetyl groups from histone tails.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

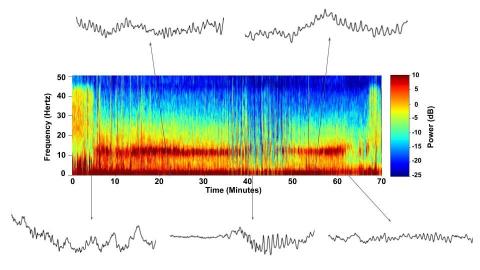

6779: Brain waves of a patient anesthetized with propofol

6779: Brain waves of a patient anesthetized with propofol

A representation of a patient’s brain waves after receiving the anesthetic propofol. All anesthetics create brain wave changes that vary depending on the patient’s age and the type and dose of anesthetic used. These changes are visible in raw electroencephalogram (EEG) readings, but they’re easier to interpret using a spectrogram where the signals are broken down by time (x-axis), frequency (y-axis), and power (color scale). This spectrogram shows the changes in brain waves before, during, and after propofol-induced anesthesia. The patient is unconscious from minute 5, upon propofol administration, through minute 69 (change in power and frequency). But, between minutes 35 and 48, the patient fell into a profound state of unconsciousness (disappearance of dark red oscillations between 8 to 12 Hz), which required the anesthesiologist to adjust the rate of propofol administration. The propofol was stopped at minute 62 and the patient woke up around minute 69.

Emery N. Brown, M.D., Ph.D., Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Media

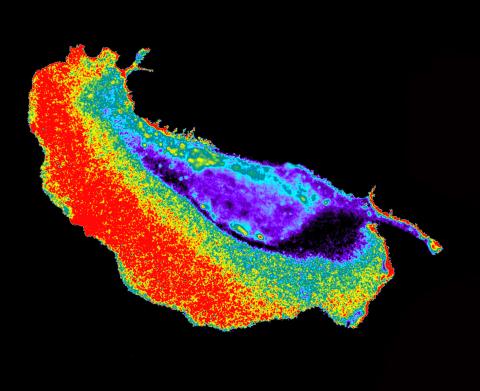

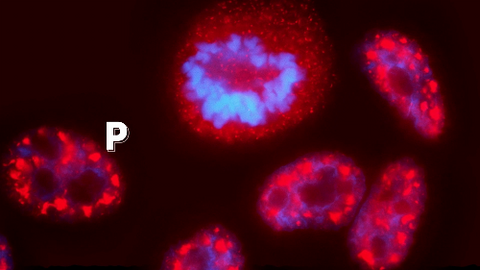

2452: Seeing signaling protein activation in cells 02

2452: Seeing signaling protein activation in cells 02

Cdc42, a member of the Rho family of small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) proteins, regulates multiple cell functions, including motility, proliferation, apoptosis, and cell morphology. In order to fulfill these diverse roles, the timing and location of Cdc42 activation must be tightly controlled. Klaus Hahn and his research group use special dyes designed to report protein conformational changes and interactions, here in living neutrophil cells. Warmer colors in this image indicate higher levels of activation. Cdc42 looks to be activated at cell protrusions.

Related to images 2451, 2453, and 2454.

Related to images 2451, 2453, and 2454.

Klaus Hahn, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Medical School

View Media

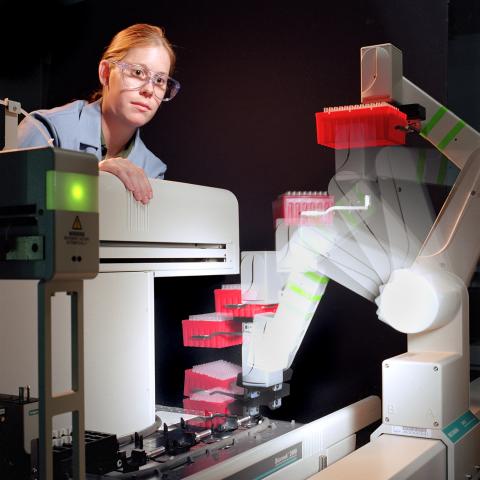

2356: Student overseeing protein cloning robot

2356: Student overseeing protein cloning robot

Student Christina Hueneke of the Midwest Center for Structural Genomics is overseeing a protein cloning robot. The robot was designed as part of an effort to exponentially increase the output of a traditional wet lab. Part of the center's goal is to cut the average cost of analyzing a protein from $200,000 to $20,000 and to slash the average time from months to days and hours.

Midwest Center for Structural Genomics

View Media

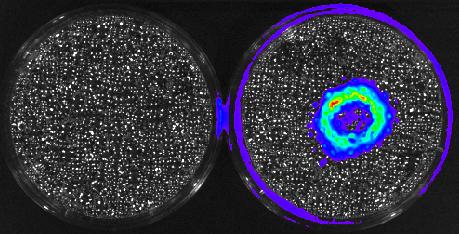

3480: Cancer Cells Glowing from Luciferin

3480: Cancer Cells Glowing from Luciferin

The activator cancer cell culture, right, contains a chemical that causes the cells to emit light when in the presence of immune cells.

Mark Sellmyer, Stanford University School of Medicine

View Media

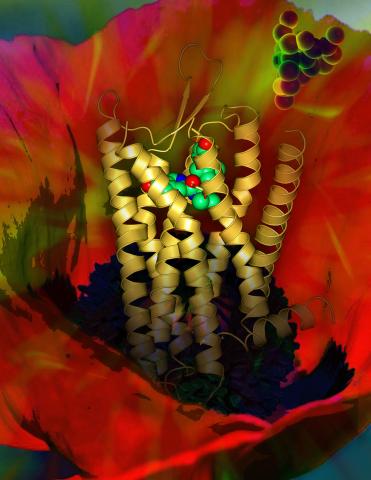

3314: Human opioid receptor structure superimposed on poppy

3314: Human opioid receptor structure superimposed on poppy

Opioid receptors on the surfaces of brain cells are involved in pleasure, pain, addiction, depression, psychosis, and other conditions. The receptors bind to both innate opioids and drugs ranging from hospital anesthetics to opium. Researchers at The Scripps Research Institute, supported by the NIGMS Protein Structure Initiative, determined the first three-dimensional structure of a human opioid receptor, a kappa-opioid receptor. In this illustration, the submicroscopic receptor structure is shown while bound to an agonist (or activator). The structure is superimposed on a poppy flower, the source of opium.

Raymond Stevens, The Scripps Research Institute

View Media

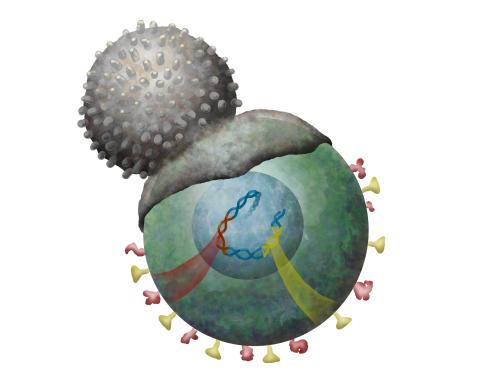

2489: Immune cell attacks cell infected with a retrovirus

2489: Immune cell attacks cell infected with a retrovirus

T cells engulf and digest cells displaying markers (or antigens) for retroviruses, such as HIV.

Kristy Whitehouse, science illustrator

View Media

6541: Pathways: What's the Connection? | Different Jobs in a Science Lab

6541: Pathways: What's the Connection? | Different Jobs in a Science Lab

Learn about some of the different jobs in a scientific laboratory and how researchers work as a team to make discoveries. Discover more resources from NIGMS’ Pathways collaboration with Scholastic. View the video on YouTube for closed captioning.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

2376: Protein purification facility

2376: Protein purification facility

The Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics protein purification facility is responsible for purifying all recombinant proteins produced by the center. The facility performs several purification steps, monitors the quality of the processes, and stores information about the biochemical properties of the purified proteins in the facility database.

Center for Eukaryotic Structural Genomics

View Media

6593: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs 6

6593: Cell-like compartments from frog eggs 6

Cell-like compartments that spontaneously emerged from scrambled frog eggs, with nuclei (blue) from frog sperm. Endoplasmic reticulum (red) and microtubules (green) are also visible. Image created using confocal microscopy.

For more photos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6584, 6585, 6586, 6591, 6592.

For videos of cell-like compartments from frog eggs view: 6587, 6588, 6589, and 6590.

Xianrui Cheng, Stanford University School of Medicine.

View Media

3618: Hair cells: the sound-sensing cells in the ear

3618: Hair cells: the sound-sensing cells in the ear

These cells get their name from the hairlike structures that extend from them into the fluid-filled tube of the inner ear. When sound reaches the ear, the hairs bend and the cells convert this movement into signals that are relayed to the brain. When we pump up the music in our cars or join tens of thousands of cheering fans at a football stadium, the noise can make the hairs bend so far that they actually break, resulting in long-term hearing loss.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Henning Horn, Brian Burke, and Colin Stewart, Institute of Medical Biology, Agency for Science, Technology, and Research, Singapore

View Media

2754: Myosin V binding to actin

2754: Myosin V binding to actin

This simulation of myosin V binding to actin was created using the software tool Protein Mechanica. With Protein Mechanica, researchers can construct models using information from a variety of sources: crystallography, cryo-EM, secondary structure descriptions, as well as user-defined solid shapes, such as spheres and cylinders. The goal is to enable experimentalists to quickly and easily simulate how different parts of a molecule interact.

Simbios, NIH Center for Biomedical Computation at Stanford

View Media

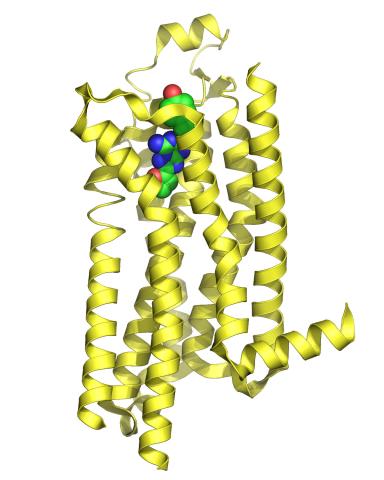

3361: A2A adenosine receptor

3361: A2A adenosine receptor

The receptor is shown bound to an inverse agonist, ZM241385.

Raymond Stevens, The Scripps Research Institute

View Media

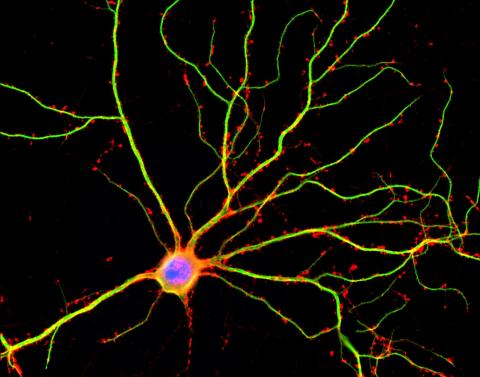

3687: Hippocampal neuron in culture

3687: Hippocampal neuron in culture

Hippocampal neuron in culture. Dendrites are green, dendritic spines are red and DNA in cell's nucleus is blue. Image is featured on Biomedical Beat blog post Anesthesia and Brain Cells: A Temporary Disruption?

Shelley Halpain, UC San Diego

View Media

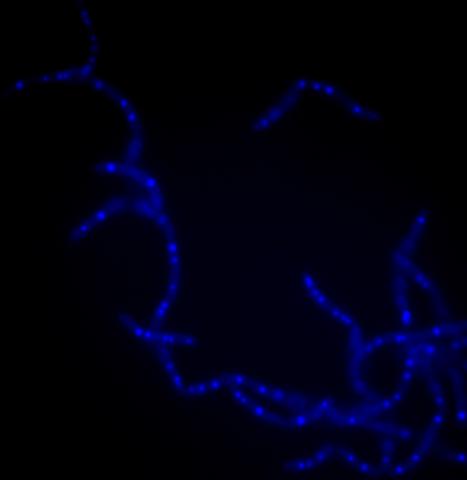

3525: Bacillus anthracis being killed

3525: Bacillus anthracis being killed

Bacillus anthracis (anthrax) cells being killed by a fluorescent trans-translation inhibitor, which disrupts bacterial protein synthesis. The inhibitor is naturally fluorescent and looks blue when it is excited by ultraviolet light in the microscope. This is a color version of Image 3481.

Kenneth Keiler, Penn State University

View Media

2724: Blinking bacteria

2724: Blinking bacteria

Like a pulsing blue shower, E. coli cells flash in synchrony. Genes inserted into each cell turn a fluorescent protein on and off at regular intervals. When enough cells grow in the colony, a phenomenon called quorum sensing allows them to switch from blinking independently to blinking in unison. Researchers can watch waves of light propagate across the colony. Adjusting the temperature, chemical composition or other conditions can change the frequency and amplitude of the waves. Because the blinks react to subtle changes in the environment, synchronized oscillators like this one could one day allow biologists to build cellular sensors that detect pollutants or help deliver drugs.

Jeff Hasty, University of California, San Diego

View Media

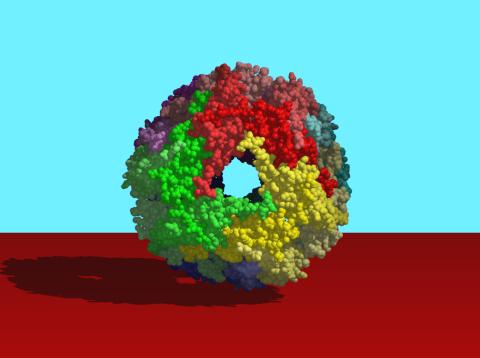

2385: Heat shock protein complex from Methanococcus jannaschii

2385: Heat shock protein complex from Methanococcus jannaschii

Model based on X-ray crystallography of the structure of a small heat shock protein complex from the bacteria, Methanococcus jannaschii. Methanococcus jannaschii is an organism that lives at near boiling temperature, and this protein complex helps it cope with the stress of high temperature. Similar complexes are produced in human cells when they are "stressed" by events such as burns, heart attacks, or strokes. The complexes help cells recover from the stressful event.

Berkeley Structural Genomics Center, PSI-1

View Media

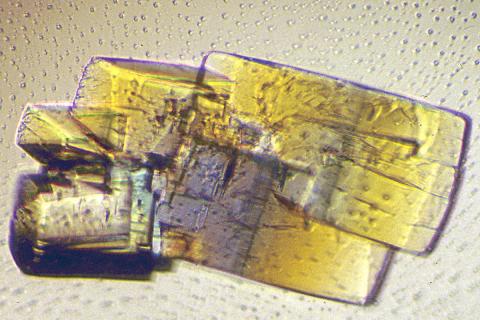

2402: RNase A (2)

2402: RNase A (2)

A crystal of RNase A protein created for X-ray crystallography, which can reveal detailed, three-dimensional protein structures.

Alex McPherson, University of California, Irvine

View Media

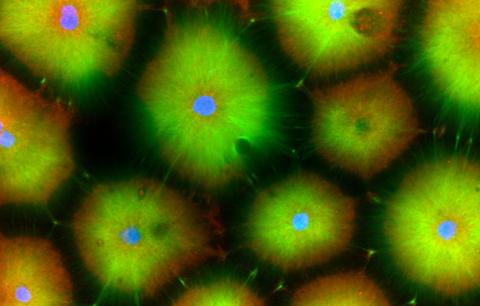

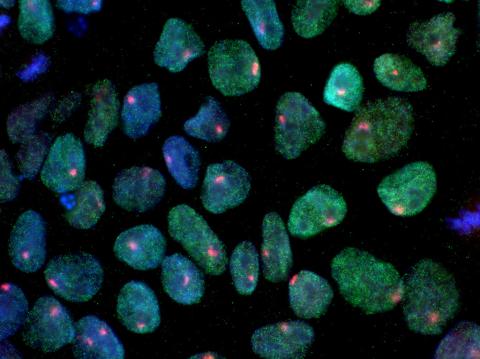

3279: Induced pluripotent stem cells from skin 02

3279: Induced pluripotent stem cells from skin 02

These induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells) were derived from a woman's skin. Blue show nuclei. Green show a protein found in iPS cells but not in skin cells (NANOG). The red dots show the inactivated X chromosome in each cell. These cells can develop into a variety of cell types. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine. Related to image 3278.

Kathrin Plath lab, University of California, Los Angeles, via CIRM

View Media

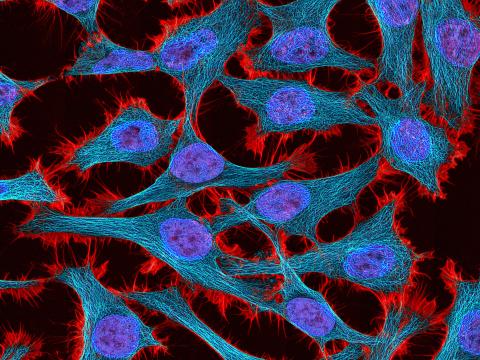

3521: HeLa cells

3521: HeLa cells

Multiphoton fluorescence image of HeLa cells stained with the actin binding toxin phalloidin (red), microtubules (cyan) and cell nuclei (blue). Nikon RTS2000MP custom laser scanning microscope. See related images 3518, 3519, 3520, 3522.

National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

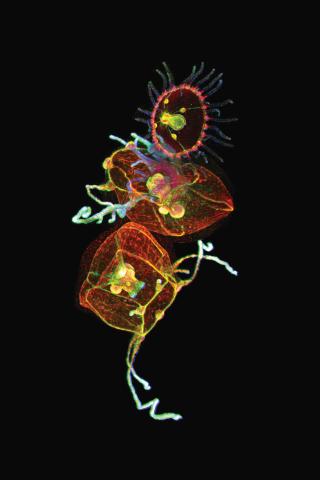

3636: Jellyfish, viewed with ZEISS Lightsheet Z.1 microscope

3636: Jellyfish, viewed with ZEISS Lightsheet Z.1 microscope

Jellyfish are especially good models for studying the evolution of embryonic tissue layers. Despite being primitive, jellyfish have a nervous system (stained green here) and musculature (red). Cell nuclei are stained blue. By studying how tissues are distributed in this simple organism, scientists can learn about the evolution of the shapes and features of diverse animals.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Helena Parra, Pompeu Fabra University, Spain

View Media

2327: Neural development

2327: Neural development

Using techniques that took 4 years to design, a team of developmental biologists showed that certain proteins can direct the subdivision of fruit fly and chicken nervous system tissue into the regions depicted here in blue, green, and red. Molecules called bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) helped form this fruit fly embryo. While scientists knew that BMPs play a major role earlier in embryonic development, they didn't know how the proteins help organize nervous tissue. The findings suggest that BMPs are part of an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for organizing the nervous system. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke also supported this work.

Mieko Mizutani and Ethan Bier, University of California, San Diego, and Henk Roelink, University of Washington

View Media

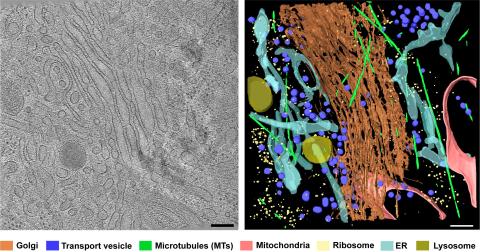

6606: Cryo-ET cross-section of the Golgi apparatus

6606: Cryo-ET cross-section of the Golgi apparatus

On the left, a cross-section slice of a rat pancreas cell captured using cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET). On the right, a 3D, color-coded version of the image highlighting cell structures. Visible features include the folded sacs of the Golgi apparatus (copper), transport vesicles (medium-sized dark-blue circles), microtubules (neon green), ribosomes (small pale-yellow circles), and lysosomes (large yellowish-green circles). Black line (bottom right of the left image) represents 200 nm. This image is a still from video 6609.

Xianjun Zhang, University of Southern California.

View Media

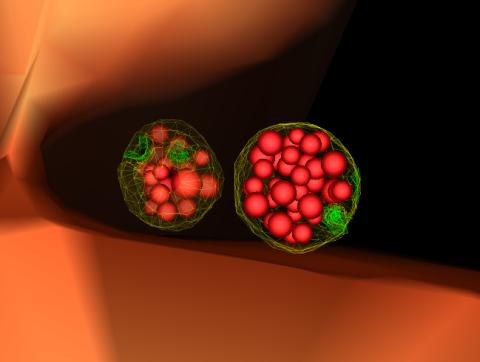

5767: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 3

5767: Multivesicular bodies containing intralumenal vesicles assemble at the vacuole 3

Collecting and transporting cellular waste and sorting it into recylable and nonrecylable pieces is a complex business in the cell. One key player in that process is the endosome, which helps collect, sort and transport worn-out or leftover proteins with the help of a protein assembly called the endosomal sorting complexes for transport (or ESCRT for short). These complexes help package proteins marked for breakdown into intralumenal vesicles, which, in turn, are enclosed in multivesicular bodies for transport to the places where the proteins are recycled or dumped. In this image, two multivesicular bodies (with yellow membranes) contain tiny intralumenal vesicles (with a diameter of only 25 nanometers; shown in red) adjacent to the cell's vacuole (in orange).

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a microscopy photograph 5768 that was used to generate this illustration and a zoomed-out version 5769 of this illustration.

Scientists working with baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) study the budding inward of the limiting membrane (green lines on top of the yellow lines) into the intralumenal vesicles. This tomogram was shot with a Tecnai F-20 high-energy electron microscope, at 29,000x magnification, with a 0.7-nm pixel, ~4-nm resolution.

To learn more about endosomes, see the Biomedical Beat blog post The Cell’s Mailroom. Related to a microscopy photograph 5768 that was used to generate this illustration and a zoomed-out version 5769 of this illustration.

Matthew West and Greg Odorizzi, University of Colorado

View Media

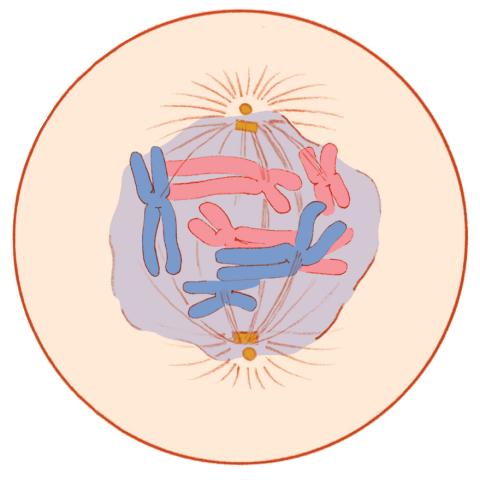

1331: Mitosis - prometaphase

1331: Mitosis - prometaphase

A cell in prometaphase during mitosis: The nuclear membrane breaks apart, and the spindle starts to interact with the chromosomes. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

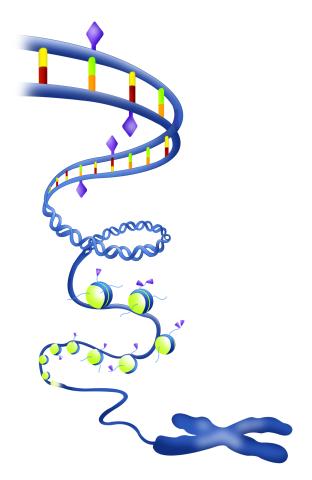

2562: Epigenetic code

2562: Epigenetic code

The "epigenetic code" controls gene activity with chemical tags that mark DNA (purple diamonds) and the "tails" of histone proteins (purple triangles). These markings help determine whether genes will be transcribed by RNA polymerase. Genes hidden from access to RNA polymerase are not expressed. See image 2563 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

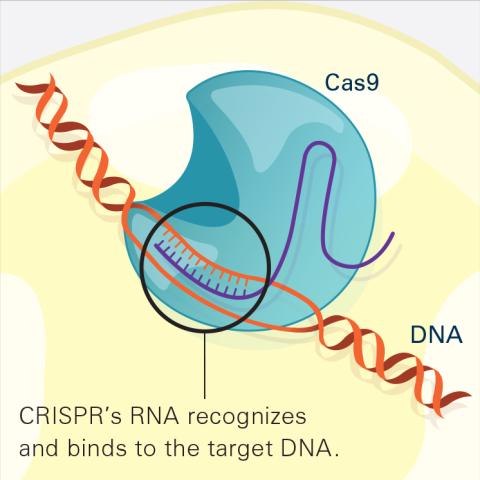

6486: CRISPR Illustration Frame 2

6486: CRISPR Illustration Frame 2

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool. The CRISPR system has two components joined together: a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence) and a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA). In this frame (2 of 4), the CRISPR machine locates the target DNA sequence once inserted into a cell.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

6963: C. elegans trapped by carnivorous fungus

6963: C. elegans trapped by carnivorous fungus

Real-time footage of Caenorhabditis elegans, a tiny roundworm, trapped by a carnivorous fungus, Arthrobotrys dactyloides. This fungus makes ring traps in response to the presence of C. elegans. When a worm enters a ring, the trap rapidly constricts so that the worm cannot move away, and the fungus then consumes the worm. The size of the imaged area is 0.7mm x 0.9mm.

This video was obtained with a polychromatic polarizing microscope (PPM) in white light that shows the polychromatic birefringent image with hue corresponding to the slow axis orientation. More information about PPM can be found in the Scientific Reports paper “Polychromatic Polarization Microscope: Bringing Colors to a Colorless World” by Shribak.

This video was obtained with a polychromatic polarizing microscope (PPM) in white light that shows the polychromatic birefringent image with hue corresponding to the slow axis orientation. More information about PPM can be found in the Scientific Reports paper “Polychromatic Polarization Microscope: Bringing Colors to a Colorless World” by Shribak.

Michael Shribak, Marine Biological Laboratory/University of Chicago.

View Media

5852: Optic nerve astrocytes

5852: Optic nerve astrocytes

Astrocytes in the cross section of a human optic nerve head

Tom Deerinck and Keunyoung (“Christine”) Kim, NCMIR

View Media

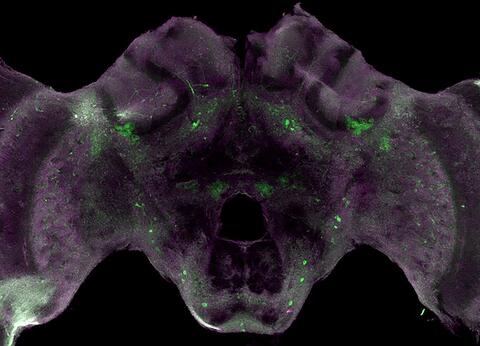

6755: Honeybee brain

6755: Honeybee brain

Insect brains, like the honeybee brain shown here, are very different in shape from human brains. Despite that, bee and human brains have a lot in common, including many of the genes and neurochemicals they rely on in order to function. The bright-green spots in this image indicate the presence of tyrosine hydroxylase, an enzyme that allows the brain to produce dopamine. Dopamine is involved in many important functions, such as the ability to experience pleasure. This image was captured using confocal microscopy.

Gene Robinson, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

View Media

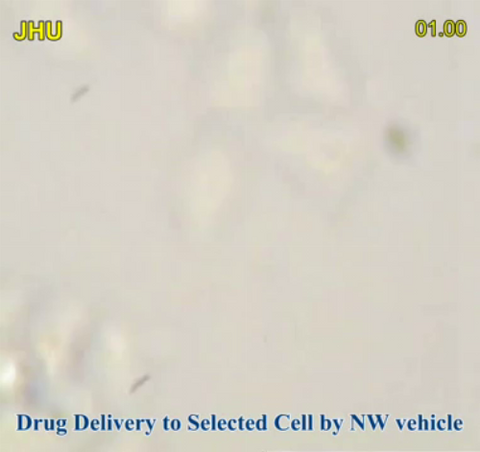

3779: Precisely Delivering Chemical Cargo to Cells

3779: Precisely Delivering Chemical Cargo to Cells

Moving protein or other molecules to specific cells to treat or examine them has been a major biological challenge. Scientists have now developed a technique for delivering chemicals to individual cells. The approach involves gold nanowires that, for example, can carry tumor-killing proteins. The advance was possible after researchers developed electric tweezers that could manipulate gold nanowires to help deliver drugs to single cells.

This movie shows the manipulation of the nanowires for drug delivery to a single cell. To learn more about this technique, see this post in the Computing Life series.

This movie shows the manipulation of the nanowires for drug delivery to a single cell. To learn more about this technique, see this post in the Computing Life series.

Nature Nanotechnology

View Media

6551: ¿Qué es la sepsis? (Sepsis Infographic)

6551: ¿Qué es la sepsis? (Sepsis Infographic)

La sepsis o septicemia es la respuesta fulminante y extrema del cuerpo a una infección. En los Estados Unidos, más de 1.7 millones de personas contraen sepsis cada año. Sin un tratamiento rápido, la sepsis puede provocar daño de los tejidos, insuficiencia orgánica y muerte. El NIGMS apoya a muchos investigadores en su trabajo para mejorar el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de la sepsis.

Vea 6536 para la versión en inglés de esta infografía.

Vea 6536 para la versión en inglés de esta infografía.

Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas Generales

View Media

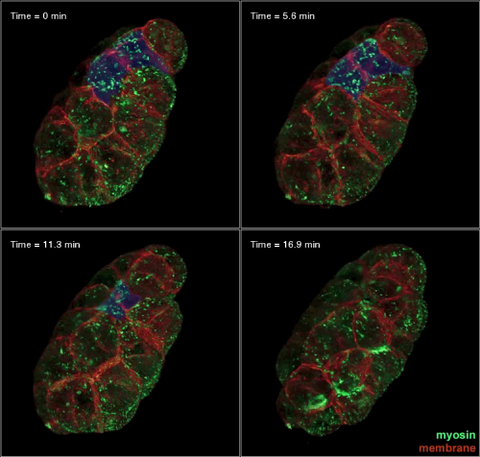

3334: Four timepoints in gastrulation

3334: Four timepoints in gastrulation

It has been said that gastrulation is the most important event in a person's life. This part of early embryonic development transforms a simple ball of cells and begins to define cell fate and the body axis. In a study published in Science magazine, NIGMS grantee Bob Goldstein and his research group studied how contractions of actomyosin filaments in C. elegans and Drosophila embryos lead to dramatic rearrangements of cell and embryonic structure. In these images, myosin (green) and plasma membrane (red) are highlighted at four timepoints in gastrulation in the roundworm C. elegans. The blue highlights in the top three frames show how cells are internalized, and the site of closure around the involuting cells is marked with an arrow in the last frame. See related image 3297.

Bob Goldstein, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill

View Media

2340: Dimeric ferredoxin-like protein from an unidentified marine microbe

2340: Dimeric ferredoxin-like protein from an unidentified marine microbe

This is the first structure of a protein derived from the metagenomic sequences collected during the Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling project. The crystal structure shows a barrel protein with a ferredoxin-like fold and a long chain fatty acid in a deep cleft (shaded red). Featured as one of the August 2007 Protein Structure Initiative Structures of the Month.

Joint Center for Structural Genomics

View Media

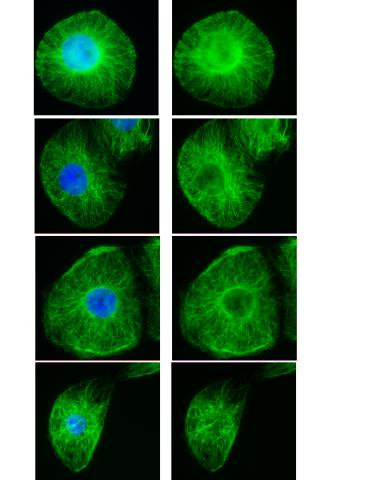

3443: Interphase in Xenopus frog cells

3443: Interphase in Xenopus frog cells

These images show frog cells in interphase. The cells are Xenopus XL177 cells, which are derived from tadpole epithelial cells. The microtubules are green and the chromosomes are blue. Related to 3442.

Claire Walczak, who took them while working as a postdoc in the laboratory of Timothy Mitchison.

View Media

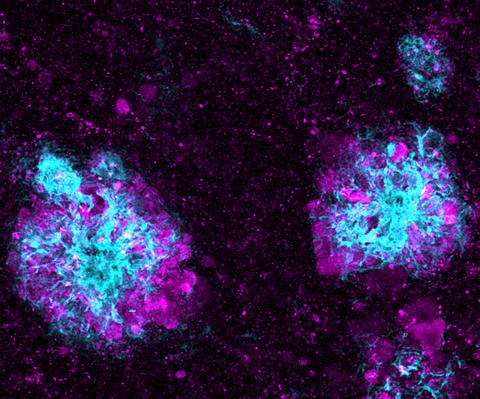

5771: Lysosome clusters around amyloid plaques

5771: Lysosome clusters around amyloid plaques

It's probably most people's least favorite activity, but we still need to do it--take out our trash. Otherwise our homes will get cluttered and smelly, and eventually, we'll get sick. The same is true for our cells: garbage disposal is an ongoing and essential activity, and our cells have a dedicated waste-management system that helps keep them clean and neat. One major waste-removal agent in the cell is the lysosome. Lysosomes are small structures, called organelles, and help the body to dispose of proteins and other molecules that have become damaged or worn out.

This image shows a massive accumulation of lysosomes (visualized with LAMP1 immunofluorescence, in purple) within nerve cells that surround amyloid plaques (visualized with beta-amyloid immunofluorescence, in light blue) in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Scientists have linked accumulation of lysosomes around amyloid plaques to impaired waste disposal in nerve cells, ultimately resulting in cell death.

This image shows a massive accumulation of lysosomes (visualized with LAMP1 immunofluorescence, in purple) within nerve cells that surround amyloid plaques (visualized with beta-amyloid immunofluorescence, in light blue) in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Scientists have linked accumulation of lysosomes around amyloid plaques to impaired waste disposal in nerve cells, ultimately resulting in cell death.

Swetha Gowrishankar and Shawn Ferguson, Yale School of Medicine

View Media

2315: Fly cells live

2315: Fly cells live

If a picture is worth a thousand words, what's a movie worth? For researchers studying cell migration, a "documentary" of fruit fly cells (bright green) traversing an egg chamber could answer longstanding questions about cell movement. Historically, researchers have been unable to watch this cell migration unfold in living ovarian tissue in real time. But by developing a culture medium that allows fly eggs to survive outside their ovarian homes, scientists can observe the nuances of cell migration as it happens. Such details may shed light on how immune cells move to a wound and why cancer cells spread to other sites. See 3594 for still image.

Denise Montell, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

View Media

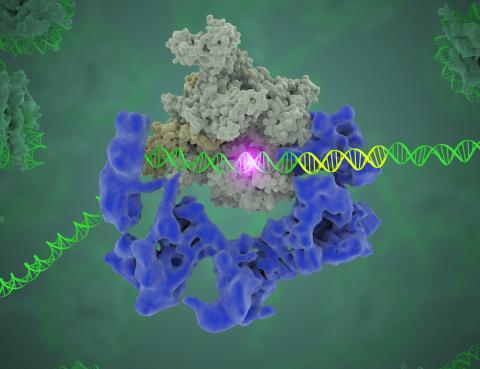

3766: TFIID complex binds DNA to start gene transcription

3766: TFIID complex binds DNA to start gene transcription

Gene transcription is a process by which the genetic information encoded in DNA is transcribed into RNA. It's essential for all life and requires the activity of proteins, called transcription factors, that detect where in a DNA strand transcription should start. In eukaryotes (i.e., those that have a nucleus and mitochondria), a protein complex comprising 14 different proteins is responsible for sniffing out transcription start sites and starting the process. This complex, called TFIID, represents the core machinery to which an enzyme, named RNA polymerase, can bind to and read the DNA and transcribe it to RNA. Scientists have used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize the TFIID-RNA polymerase-DNA complex in unprecedented detail. In this illustration, TFIID (blue) contacts the DNA and recruits the RNA polymerase (gray) for gene transcription. The start of the transcribed gene is shown with a flash of light. To learn more about the research that has shed new light on gene transcription, see this news release from Berkeley Lab. Related to video 5730.

Eva Nogales, Berkeley Lab

View Media

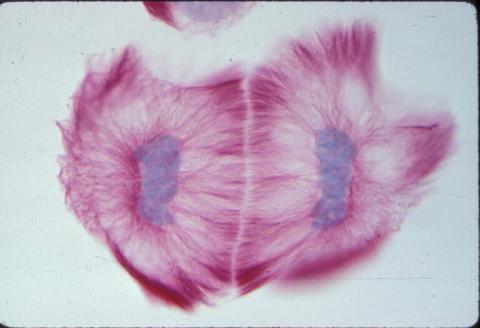

1019: Lily mitosis 13

1019: Lily mitosis 13

A light microscope image of cells from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, two cells have formed after a round of mitosis.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1016, 1017, 1018, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

5752: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 2

5752: Genetically identical mycobacteria respond differently to antibiotic 2

Antibiotic resistance in microbes is a serious health concern. So researchers have turned their attention to how bacteria undo the action of some antibiotics. Here, scientists set out to find the conditions that help individual bacterial cells survive in the presence of the antibiotic rifampicin. The research team used Mycobacterium smegmatis, a more harmless relative of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which infects the lung and other organs to cause serious disease.

In this video, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to image 5751.

In this video, genetically identical mycobacteria are growing in a miniature growth chamber called a microfluidic chamber. Using live imaging, the researchers found that individual mycobacteria will respond differently to the antibiotic, depending on the growth stage and other timing factors. The researchers used genetic tagging with green fluorescent protein to distinguish cells that can resist rifampicin and those that cannot. With this gene tag, cells tolerant of the antibiotic light up in green and those that are susceptible in violet, enabling the team to monitor the cells' responses in real time.

To learn more about how the researchers studied antibiotic resistance in mycobacteria, see this news release from Tufts University. Related to image 5751.

Bree Aldridge, Tufts University

View Media

3566: Mouse colon with gut bacteria

3566: Mouse colon with gut bacteria

A section of mouse colon with gut bacteria (center, in green) residing within a protective pocket. Understanding how microorganisms colonize the gut could help devise ways to correct for abnormal changes in bacterial communities that are associated with disorders like inflammatory bowel disease.

Sarkis K. Mazmanian, California Institute of Technology

View Media

2727: Proteins related to myotonic dystrophy

2727: Proteins related to myotonic dystrophy

Myotonic dystrophy is thought to be caused by the binding of a protein called Mbnl1 to abnormal RNA repeats. In these two images of the same muscle precursor cell, the top image shows the location of the Mbnl1 splicing factor (green) and the bottom image shows the location of RNA repeats (red) inside the cell nucleus (blue). The white arrows point to two large foci in the cell nucleus where Mbnl1 is sequestered with RNA.

Manuel Ares, University of California, Santa Cruz

View Media

3417: X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor 5

3417: X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor 5

X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor. Related to images 3413, 3414, 3415, 3416, 3418, and 3419.

Markus A. Seeliger, Stony Brook University Medical School and David R. Liu, Harvard University

View Media

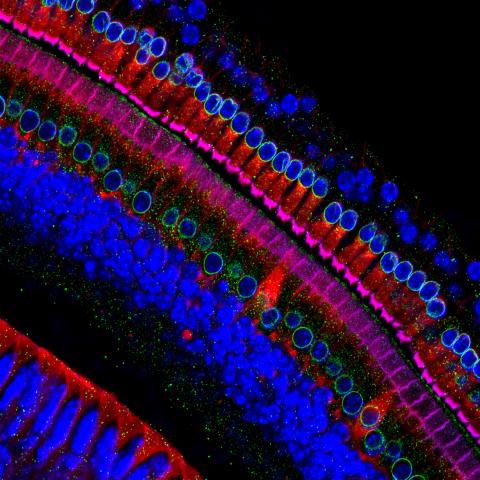

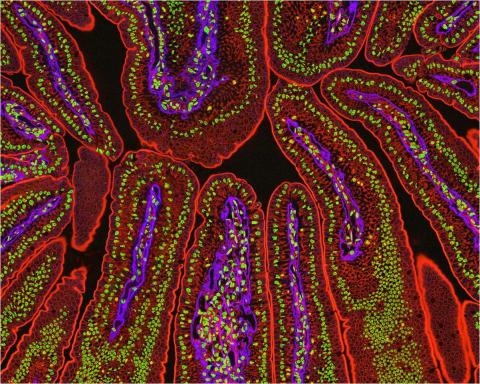

3390: NCMIR Intestine-2

3390: NCMIR Intestine-2

The small intestine is where most of our nutrients from the food we eat are absorbed into the bloodstream. The walls of the intestine contain small finger-like projections called villi which increase the organ's surface area, enhancing nutrient absorption. It consists of the duodenum, which connects to the stomach, the jejenum and the ileum, which connects with the large intestine. Related to image 3389.

Tom Deerinck, National Center for Microscopy and Imaging Research (NCMIR)

View Media

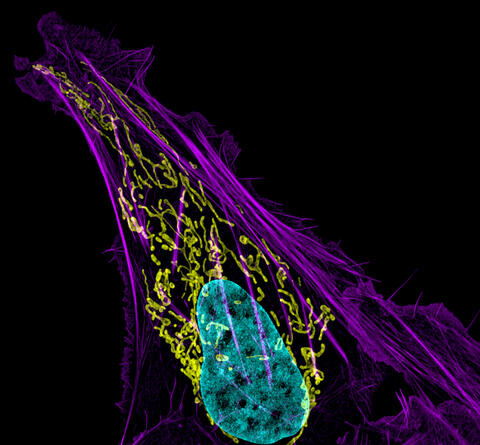

3626: Bone cancer cell

3626: Bone cancer cell

This image shows an osteosarcoma cell with DNA in blue, energy factories (mitochondria) in yellow, and actin filaments—part of the cellular skeleton—in purple. One of the few cancers that originate in the bones, osteosarcoma is rare, with about a thousand new cases diagnosed each year in the United States.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

Dylan Burnette and Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz, NICHD

View Media

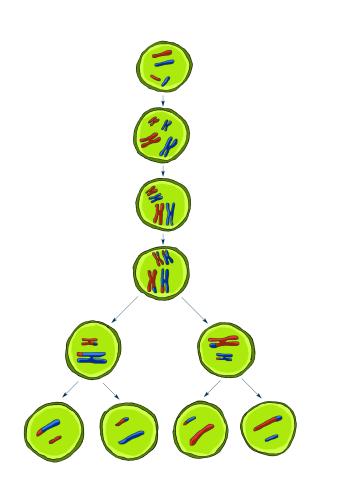

2545: Meiosis illustration

2545: Meiosis illustration

Meiosis is the process whereby a cell reduces its chromosomes from diploid to haploid in creating eggs or sperm. See image 2546 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

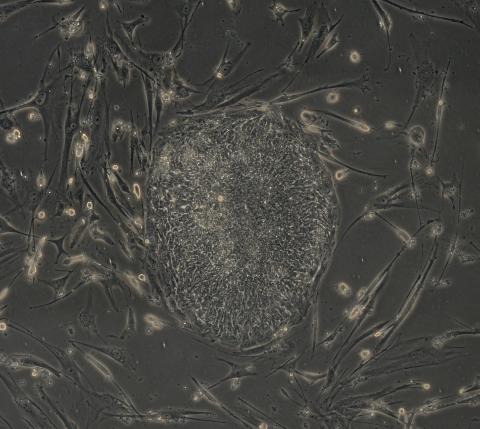

2606: Induced stem cells from adult skin 04

2606: Induced stem cells from adult skin 04

The human skin cells pictured contain genetic modifications that make them pluripotent, essentially equivalent to embryonic stem cells. A scientific team from the University of Wisconsin-Madison including researchers Junying Yu, James Thomson, and their colleagues produced the transformation by introducing a set of four genes into human fibroblasts, skin cells that are easy to obtain and grow in culture.

James Thomson, University of Wisconsin-Madison

View Media

2767: Research mentor and student

2767: Research mentor and student

A research mentor (Lori Eidson) and student (Nina Waldron, on the microscope) were 2009 members of the BRAIN (Behavioral Research Advancements In Neuroscience) program at Georgia State University in Atlanta. This program is an undergraduate summer research experience funded in part by NIGMS.

Elizabeth Weaver, Georgia State University

View Media