Switch to List View

Image and Video Gallery

This is a searchable collection of scientific photos, illustrations, and videos. The images and videos in this gallery are licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial ShareAlike 3.0. This license lets you remix, tweak, and build upon this work non-commercially, as long as you credit and license your new creations under identical terms.

6555: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 2)

6555: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 2)

Floral pattern emerging as two bacterial species, motile Acinetobacter baylyi (red) and non-motile Escherichia coli (green), are grown together for 48 hours on 1% agar surface from a small inoculum in the center of a Petri dish.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6553 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

L. Xiong et al, eLife 2020;9: e48885

View Media

1083: Natcher Building 03

1083: Natcher Building 03

NIGMS staff are located in the Natcher Building on the NIH campus.

Alisa Machalek, National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

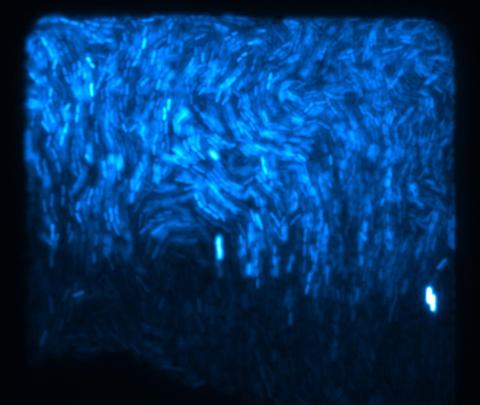

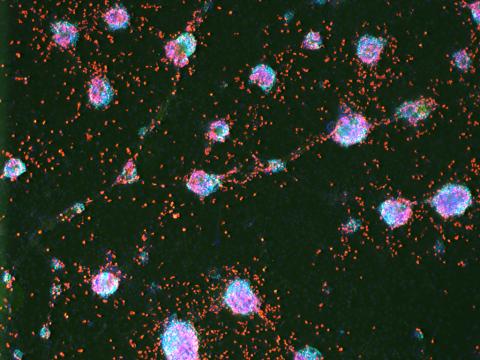

3268: Fluorescent E. coli bacteria

3268: Fluorescent E. coli bacteria

Bioengineers were able to coax bacteria to blink in unison on microfluidic chips. They called each blinking bacterial colony a biopixel. Thousands of fluorescent E. coli bacteria, shown here, make up a biopixel. Related to images 3265 and 3266. From a UC San Diego news release, "Researchers create living 'neon signs' composed of millions of glowing bacteria."

Jeff Hasty Lab, UC San Diego

View Media

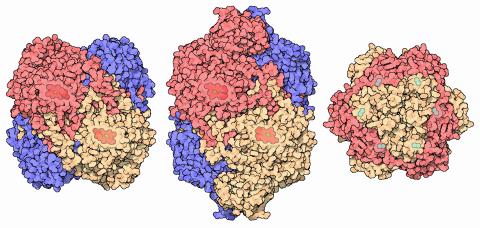

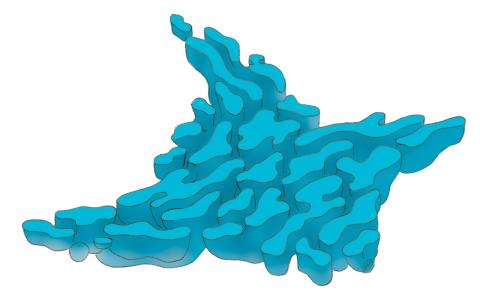

7003: Catalase diversity

7003: Catalase diversity

Catalases are some of the most efficient enzymes found in cells. Each catalase molecule can decompose millions of hydrogen peroxide molecules every second—working as an antioxidant to protect cells from the dangerous form of reactive oxygen. Different cells build different types of catalases. The human catalase that protects our red blood cells, shown on the left from PDB entry 1QQW, is composed of four identical subunits and uses a heme/iron group to perform the reaction. Many bacteria scavenge hydrogen peroxide with a larger catalase, shown in the center from PDB entry 1IPH, that uses a similar arrangement of iron and heme. Other bacteria protect themselves with an entirely different catalase that uses manganese ions instead of heme, as shown at the right from PDB entry 1JKU.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

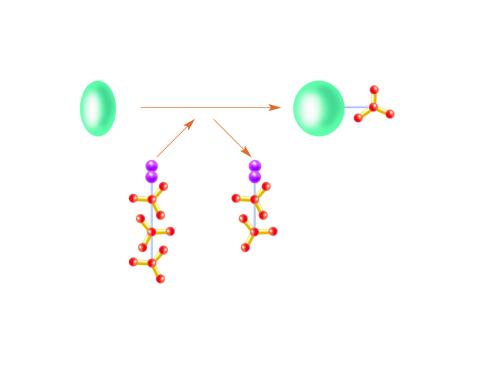

2534: Kinases

2534: Kinases

Kinases are enzymes that add phosphate groups (red-yellow structures) to proteins (green), assigning the proteins a code. In this reaction, an intermediate molecule called ATP (adenosine triphosphate) donates a phosphate group from itself, becoming ADP (adenosine diphosphate). See image 2535 for a labeled version of this illustration. Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

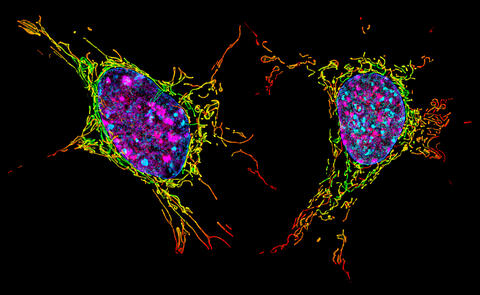

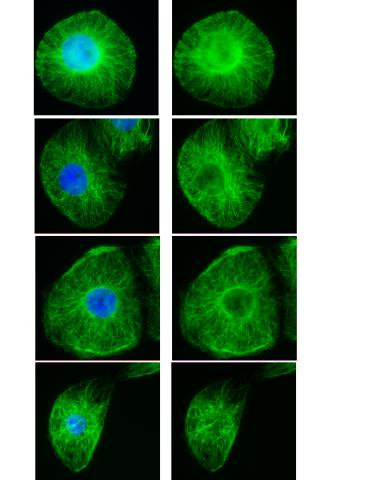

6789: Two mouse fibroblast cells

6789: Two mouse fibroblast cells

Two mouse fibroblasts, one of the most common types of cells in mammalian connective tissue. They play a key role in wound healing and tissue repair. This image was captured using structured illumination microscopy.

Dylan T. Burnette, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

View Media

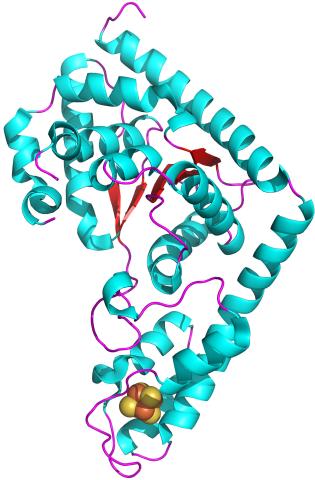

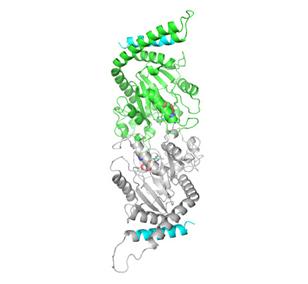

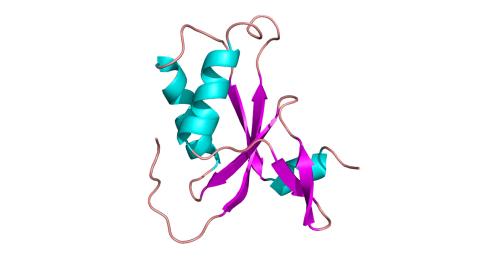

2483: Trp_RS - tryptophanyl tRNA-synthetase family of enzymes

2483: Trp_RS - tryptophanyl tRNA-synthetase family of enzymes

This image represents the structure of TrpRS, a novel member of the tryptophanyl tRNA-synthetase family of enzymes. By helping to link the amino acid tryptophan to a tRNA molecule, TrpRS primes the amino acid for use in protein synthesis. A cluster of iron and sulfur atoms (orange and red spheres) was unexpectedly found in the anti-codon domain, a key part of the molecule, and appears to be critical for the function of the enzyme. TrpRS was discovered in Thermotoga maritima, a rod-shaped bacterium that flourishes in high temperatures.

View Media

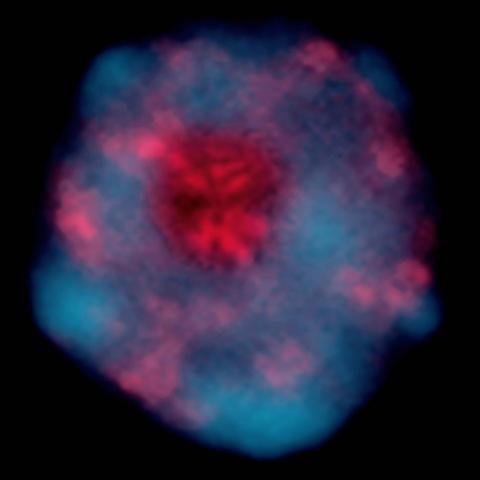

6553: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 1)

6553: Floral pattern in a mixture of two bacterial species, Acinetobacter baylyi and Escherichia coli, grown on a semi-solid agar for 48 hours (photo 1)

Floral pattern emerging as two bacterial species, motile Acinetobacter baylyi (red) and non-motile Escherichia coli (green), are grown together for 48 hours on 1% agar surface from a small inoculum in the center of a Petri dish.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

See 6557 for a photo of this process at 24 hours on 0.75% agar surface.

See 6555 for another photo of this process at 48 hours on 1% agar surface.

See 6556 for a photo of this process at 72 hours on 0.5% agar surface.

See 6550 for a video of this process.

L. Xiong et al, eLife 2020;9: e48885

View Media

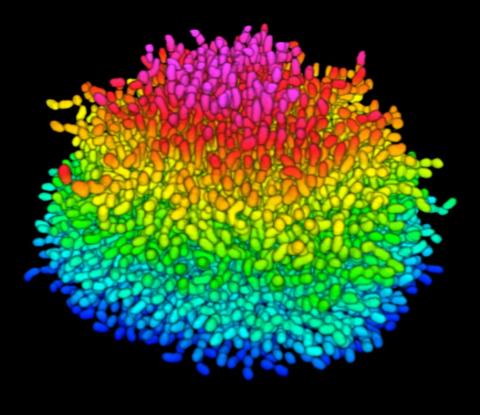

5825: A Growing Bacterial Biofilm

5825: A Growing Bacterial Biofilm

A growing Vibrio cholerae (cholera) biofilm. Cholera bacteria form colonies called biofilms that enable them to resist antibiotic therapy within the body and other challenges to their growth.

Each slightly curved comma shape represents an individual bacterium from assembled confocal microscopy images. Different colors show each bacterium’s position in the biofilm in relation to the surface on which the film is growing.

Each slightly curved comma shape represents an individual bacterium from assembled confocal microscopy images. Different colors show each bacterium’s position in the biofilm in relation to the surface on which the film is growing.

Jing Yan, Ph.D., and Bonnie Bassler, Ph.D., Department of Molecular Biology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ.

View Media

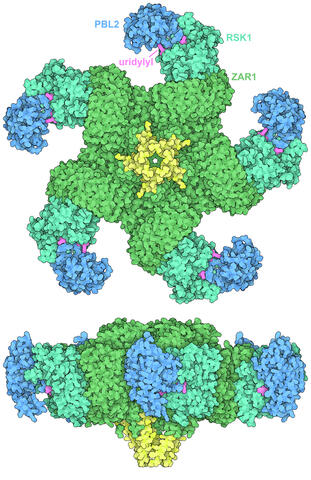

7002: Plant resistosome

7002: Plant resistosome

The research organism Arabidopsis thaliana forms a large molecular machine called a resistosome to fight off infections. This illustration shows the top and side views of the fully-formed resistosome assembly (PDB entry 6J5T), composed of different proteins including one the plant uses as a decoy, PBL2 (dark blue), that gets uridylylated to begin the process of building the resistosome (uridylyl groups in magenta). Other proteins include RSK1 (turquoise) and ZAR1 (green) subunits. The ends of the ZAR1 subunits (yellow) form a funnel-like protrusion on one side of the assembly (seen in the side view). The funnel can carry out the critical protective function of the resistosome by inserting itself into the cell membrane to form a pore, which leads to a localized programmed cell death. The death of the infected cell helps protect the rest of the plant.

Amy Wu and Christine Zardecki, RCSB Protein Data Bank.

View Media

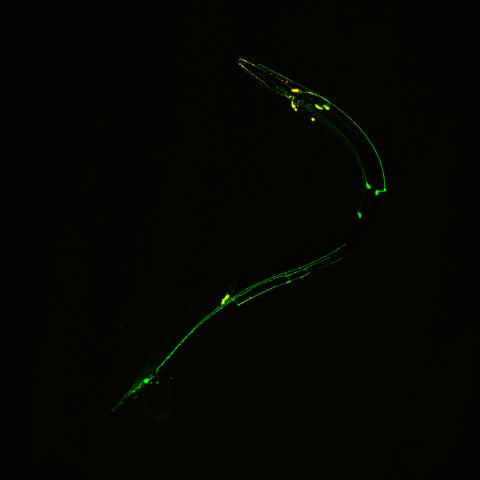

3252: Neural circuits in worms similar to those in humans

3252: Neural circuits in worms similar to those in humans

Green and yellow fluorescence mark the processes and cell bodies of some C. elegans neurons. Researchers have found that the strategies used by this tiny roundworm to control its motions are remarkably similar to those used by the human brain to command movement of our body parts. From a November 2011 University of Michigan news release.

Shawn Xu, University of Michigan

View Media

2744: Dynamin structure

2744: Dynamin structure

When a molecule arrives at a cell's outer membrane, the membrane creates a pouch around the molecule that protrudes inward. Directed by a protein called dynamin, the pouch then gets pinched off to form a vesicle that carries the molecule to the right place inside the cell. To better understand how dynamin performs its vital pouch-pinching role, researchers determined its structure. Based on the structure, they proposed that a dynamin "collar" at the pouch's base twists ever tighter until the vesicle pops free. Because cells absorb many drugs through vesicles, the discovery could lead to new drug delivery methods.

Josh Chappie, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIH

View Media

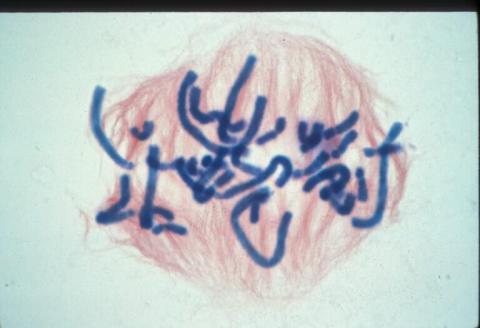

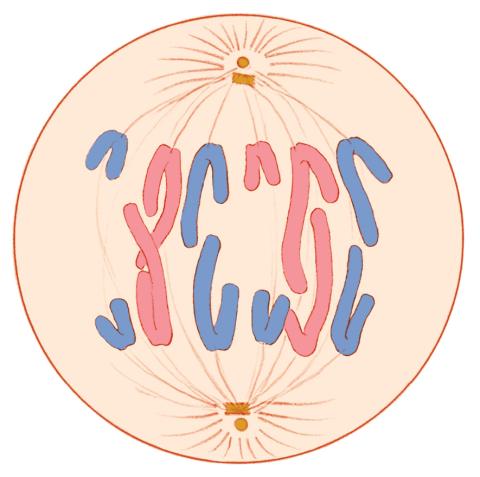

1016: Lily mitosis 06

1016: Lily mitosis 06

A light microscope image of a cell from the endosperm of an African globe lily (Scadoxus katherinae). This is one frame of a time-lapse sequence that shows cell division in action. The lily is considered a good organism for studying cell division because its chromosomes are much thicker and easier to see than human ones. Staining shows microtubules in red and chromosomes in blue. Here, condensed chromosomes are clearly visible and are starting to line up.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Related to images 1010, 1011, 1012, 1013, 1014, 1015, 1017, 1018, 1019, and 1021.

Andrew S. Bajer, University of Oregon, Eugene

View Media

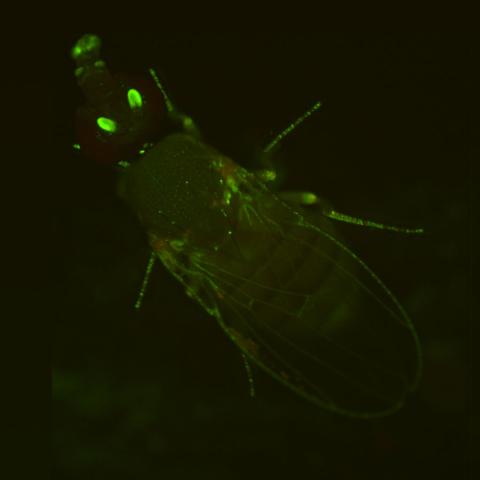

2417: Fly by night

2417: Fly by night

This fruit fly expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the same pattern as the period gene, a gene that regulates circadian rhythm and is expressed in all sensory neurons on the surface of the fly.

Jay Hirsh, University of Virginia

View Media

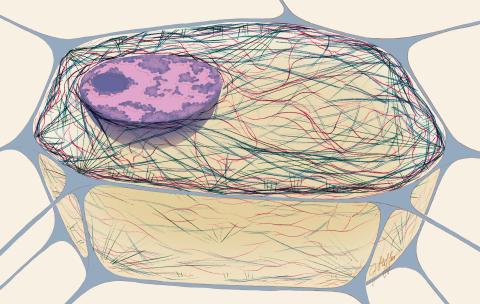

1272: Cytoskeleton

1272: Cytoskeleton

The three fibers of the cytoskeleton--microtubules in blue, intermediate filaments in red, and actin in green--play countless roles in the cell.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

2763: Fused, dicentric chromosomes

2763: Fused, dicentric chromosomes

This fused chromosome has two functional centromeres, shown as two sets of red and green dots. Centromeres are DNA/protein complexes that are key to splitting the chromosomes evenly during cell division. When dicentric chromosomes like this one are formed in a person, fertility problems or other difficulties may arise. Normal chromosomes carrying a single centromere (one set of red and green dots) are also visible in this image.

Beth A. Sullivan, Duke University

View Media

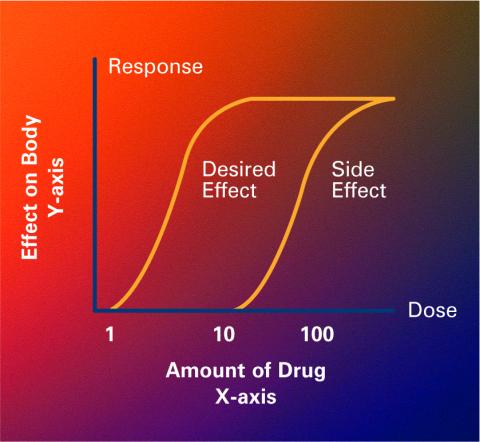

2533: Dose response curves

2533: Dose response curves

Dose-response curves determine how much of a drug (X-axis) causes a particular effect, or a side effect, in the body (Y-axis). Featured in Medicines By Design.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

3427: Antitoxin GhoS (Illustration 1)

3427: Antitoxin GhoS (Illustration 1)

Structure of the bacterial antitoxin protein GhoS. GhoS inhibits the production of a bacterial toxin, GhoT, which can contribute to antibiotic resistance. GhoS is the first known bacterial antitoxin that works by cleaving the messenger RNA that carries the instructions for making the toxin. More information can be found in the paper: Wang X, Lord DM, Cheng HY, Osbourne DO, Hong SH, Sanchez-Torres V, Quiroga C, Zheng K, Herrmann T, Peti W, Benedik MJ, Page R, Wood TK. A new type V toxin-antitoxin system where mRNA for toxin GhoT is cleaved by antitoxin GhoS. Nat Chem Biol. 2012 Oct;8(10):855-61. Related to 3428.

Rebecca Page and Wolfgang Peti, Brown University and Thomas K. Wood, Pennsylvania State University

View Media

5815: Introduction to Genome Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9

5815: Introduction to Genome Editing Using CRISPR/Cas9

Genome editing using CRISPR/Cas9 is a rapidly expanding field of scientific research with emerging applications in disease treatment, medical therapeutics and bioenergy, just to name a few. This technology is now being used in laboratories all over the world to enhance our understanding of how living biological systems work, how to improve treatments for genetic diseases and how to develop energy solutions for a better future.

Janet Iwasa

View Media

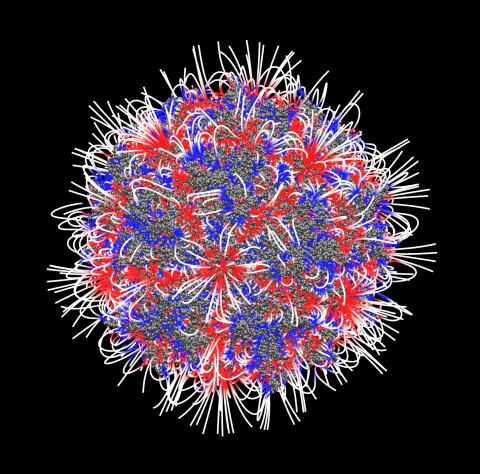

3374: Electrostatic map of the adeno-associated virus

3374: Electrostatic map of the adeno-associated virus

The new highly efficient parallelized DelPhi software was used to calculate the potential map distribution of an entire virus, the adeno-associated virus, which is made up of more than 484,000 atoms. Despite the relatively large dimension of this biological system, resulting in 815x815x815 mesh points, the parallelized DelPhi, utilizing 100 CPUs, completed the calculations within less than three minutes. Related to image 3375.

Emil Alexov, Clemson University

View Media

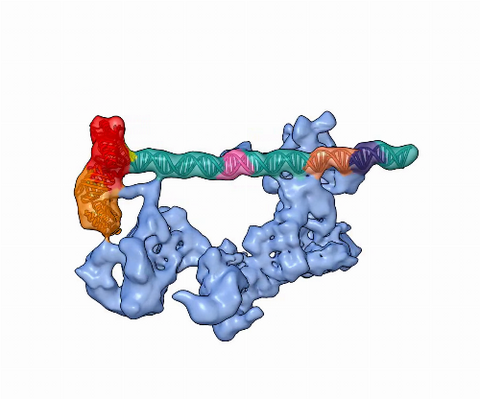

5730: Dynamic cryo-EM model of the human transcription preinitiation complex

5730: Dynamic cryo-EM model of the human transcription preinitiation complex

Gene transcription is a process by which information encoded in DNA is transcribed into RNA. It's essential for all life and requires the activity of proteins, called transcription factors, that detect where in a DNA strand transcription should start. In eukaryotes (i.e., those that have a nucleus and mitochondria), a protein complex comprising 14 different proteins is responsible for sniffing out transcription start sites and starting the process. This complex represents the core machinery to which an enzyme, named RNA polymerase, can bind to and read the DNA and transcribe it to RNA. Scientists have used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to visualize the TFIID-RNA polymerase-DNA complex in unprecedented detail. This animation shows the different TFIID components as they contact DNA and recruit the RNA polymerase for gene transcription.

To learn more about the research that has shed new light on gene transcription, see this news release from Berkeley Lab.

Related to image 3766.

To learn more about the research that has shed new light on gene transcription, see this news release from Berkeley Lab.

Related to image 3766.

Eva Nogales, Berkeley Lab

View Media

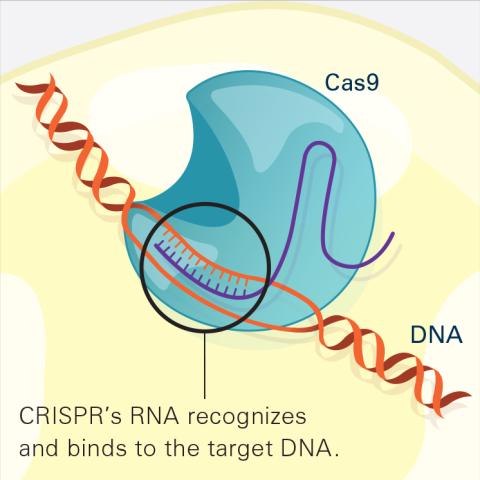

6486: CRISPR Illustration Frame 2

6486: CRISPR Illustration Frame 2

This illustration shows, in simplified terms, how the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used as a gene-editing tool. The CRISPR system has two components joined together: a finely tuned targeting device (a small strand of RNA programmed to look for a specific DNA sequence) and a strong cutting device (an enzyme called Cas9 that can cut through a double strand of DNA). In this frame (2 of 4), the CRISPR machine locates the target DNA sequence once inserted into a cell.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

For an explanation and overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 system, see the iBiology video, and find the full CRIPSR illustration here.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

View Media

5757: Pigment cells in the fin of pearl danio

5757: Pigment cells in the fin of pearl danio

Pigment cells are cells that give skin its color. In fishes and amphibians, like frogs and salamanders, pigment cells are responsible for the characteristic skin patterns that help these organisms to blend into their surroundings or attract mates. The pigment cells are derived from neural crest cells, which are cells originating from the neural tube in the early embryo. This image shows pigment cells in the fin of pearl danio, a close relative of the popular laboratory animal zebrafish. Investigating pigment cell formation and migration in animals helps answer important fundamental questions about the factors that control pigmentation in the skin of animals, including humans. Related to images 5754, 5755, 5756 and 5758.

David Parichy, University of Washington

View Media

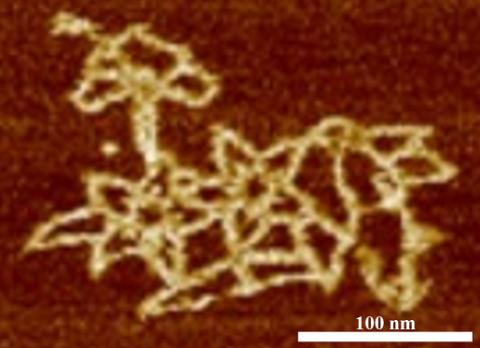

3690: Microscopy image of bird-and-flower DNA origami

3690: Microscopy image of bird-and-flower DNA origami

An atomic force microscopy image shows DNA folded into an intricate, computer-designed structure. Image is featured on Biomedical Beat blog post Cool Image: DNA Origami. See also related image 3689 .

Hao Yan, Arizona State University

View Media

6775: Tracking embryonic zebrafish cells

6775: Tracking embryonic zebrafish cells

To better understand cell movements in developing embryos, researchers isolated cells from early zebrafish embryos and grew them as clusters. Provided with the right signals, the clusters replicated some cell movements seen in intact embryos. Each line in this image depicts the movement of a single cell. The image was created using time-lapse confocal microscopy. Related to video 6776.

Liliana Solnica-Krezel, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

View Media

2637: Activated mast cell surface

2637: Activated mast cell surface

A scanning electron microscope image of an activated mast cell. This image illustrates the interesting topography of the cell membrane, which is populated with receptors. The distribution of receptors may affect cell signaling. This image relates to a July 27, 2009 article in Computing Life.

Bridget Wilson, University of New Mexico

View Media

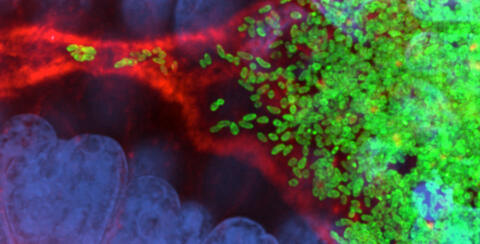

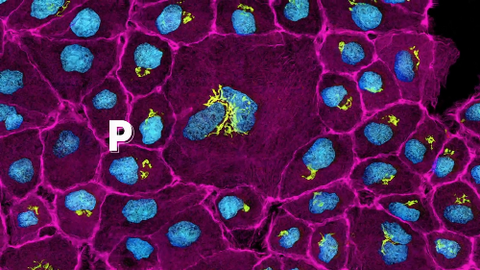

7015: Bacterial cells migrating through the tissues of the squid light organ

7015: Bacterial cells migrating through the tissues of the squid light organ

Vibrio fischeri cells (~ 2 mm), labeled with green fluorescent protein (GFP), passing through a very narrow bottleneck in the tissues (red) of the Hawaiian bobtail squid, Euprymna scolopes, on the way to the crypts where the symbiont population resides. This image was taken using a confocal fluorescence microscope.

Margaret J. McFall-Ngai, Carnegie Institution for Science/California Institute of Technology, and Edward G. Ruby, California Institute of Technology.

View Media

2318: Gene silencing

2318: Gene silencing

Pretty in pink, the enzyme histone deacetylase (HDA6) stands out against a background of blue-tinted DNA in the nucleus of an Arabidopsis plant cell. Here, HDA6 concentrates in the nucleolus (top center), where ribosomal RNA genes reside. The enzyme silences the ribosomal RNA genes from one parent while those from the other parent remain active. This chromosome-specific silencing of ribosomal RNA genes is an unusual phenomenon observed in hybrid plants.

Olga Pontes and Craig Pikaard, Washington University

View Media

2431: Fruit fly embryo

2431: Fruit fly embryo

Cells in an early-stage fruit fly embryo, showing the DIAP1 protein (pink), an inhibitor of apoptosis.

Hermann Steller, Rockefeller University

View Media

2579: Bottles of warfarin

2579: Bottles of warfarin

In 2007, the FDA modified warfarin's label to indicate that genetic makeup may affect patient response to the drug. The widely used blood thinner is sold under the brand name Coumadin®. Scientists involved in the NIH Pharmacogenetics Research Network are investigating whether genetic information can be used to improve optimal dosage prediction for patients.

Alisa Machalek, NIGMS/NIH

View Media

3277: Human ES cells turn into insulin-producing cells

3277: Human ES cells turn into insulin-producing cells

Human embryonic stem cells were differentiated into cells like those found in the pancreas (blue), which give rise to insulin-producing cells (red). When implanted in mice, the stem cell-derived pancreatic cells can replace the insulin that isn't produced in type 1 diabetes. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Eugene Brandon, ViaCyte, via CIRM

View Media

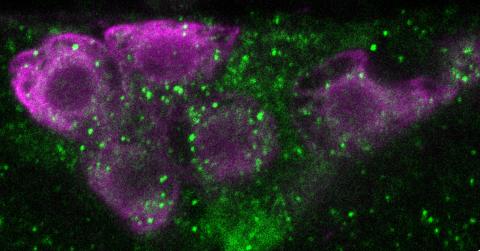

6982: Insulin production and fat sensing in fruit flies

6982: Insulin production and fat sensing in fruit flies

Fourteen neurons (magenta) in the adult Drosophila brain produce insulin, and fat tissue sends packets of lipids to the brain via the lipoprotein carriers (green). This image was captured using a confocal microscope and shows a maximum intensity projection of many slices.

Related to images 6983, 6984, and 6985.

Related to images 6983, 6984, and 6985.

Akhila Rajan, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center

View Media

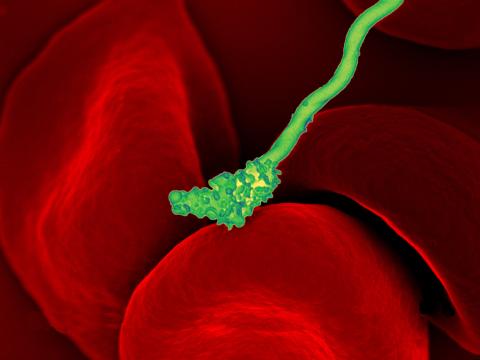

3586: Human blood cells with Borrelia hermsii, a bacterium that causes relapsing fever

3586: Human blood cells with Borrelia hermsii, a bacterium that causes relapsing fever

Relapsing fever is caused by a bacterium and transmitted by certain soft-bodied ticks or body lice. The disease is seldom fatal in humans, but it can be very serious and prolonged. This scanning electron micrograph shows Borrelia hermsii (green), one of the bacterial species that causes the disease, interacting with red blood cells. Micrograph by Robert Fischer, NIAID.

For more information on this see, relapsing fever.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

For more information on this see, relapsing fever.

This image was part of the Life: Magnified exhibit that ran from June 3, 2014, to January 21, 2015, at Dulles International Airport.

NIAID

View Media

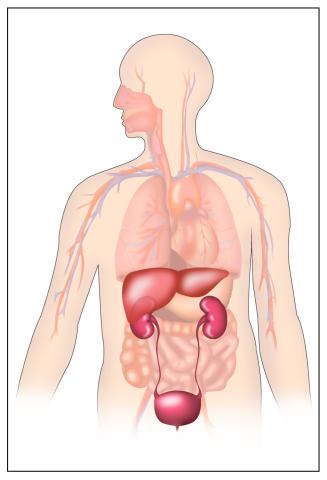

2496: Body toxins

2496: Body toxins

Body organs such as the liver and kidneys process chemicals and toxins. These "target" organs are susceptible to damage caused by these substances. See image 2497 for a labeled version of this illustration.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

2594: Katanin protein regulates anaphase

2594: Katanin protein regulates anaphase

The microtubule severing protein, katanin, localizes to chromosomes and regulates anaphase A in mitosis. The movement of chromosomes on the mitotic spindle requires the depolymerization of microtubule ends. The figure shows the mitotic localization of the microtubule severing protein katanin (green) relative to spindle microtubules (red) and kinetochores/chromosomes (blue). Katanin targets to chromosomes during both metaphase (top) and anaphase (bottom) and is responsible for inducing the depolymerization of attached microtubule plus-ends. This image was a finalist in the 2008 Drosophila Image Award.

David Sharp, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

View Media

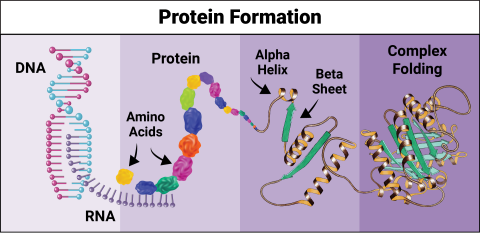

6603: Protein formation

6603: Protein formation

Proteins are 3D structures made up of smaller units. DNA is transcribed to RNA, which in turn is translated into amino acids. Amino acids form a protein strand, which has sections of corkscrew-like coils, called alpha helices, and other sections that fold flat, called beta sheets. The protein then goes through complex folding to produce the 3D structure.

NIGMS, with the folded protein illustration adapted from Jane Richardson, Duke University Medical Center

View Media

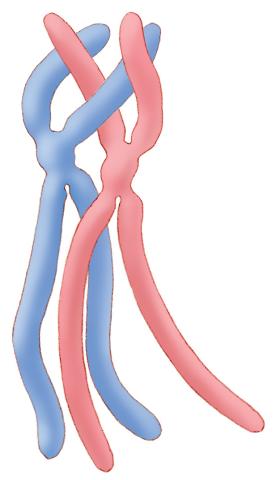

1315: Chromosomes before crossing over

1315: Chromosomes before crossing over

Duplicated pair of chromosomes lined up and ready to cross over.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

1292: Smooth ER

1292: Smooth ER

The endoplasmic reticulum comes in two types: Rough ER is covered with ribosomes and prepares newly made proteins; smooth ER specializes in making lipids and breaking down toxic molecules.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

6538: Pathways: The Fascinating Cells of Research Organisms

6538: Pathways: The Fascinating Cells of Research Organisms

Learn how research organisms, such as fruit flies and mice, can help us understand and treat human diseases. Discover more resources from NIGMS’ Pathways collaboration with Scholastic. View the video on YouTube for closed captioning.

National Institute of General Medical Sciences

View Media

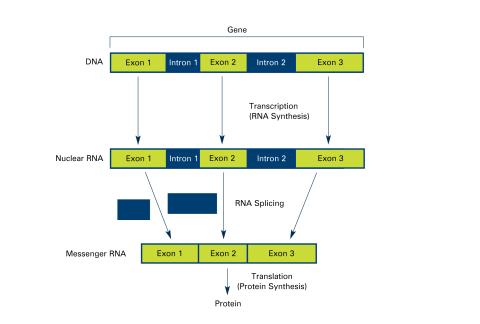

2551: Introns (with labels)

2551: Introns (with labels)

Genes are often interrupted by stretches of DNA (introns, blue) that do not contain instructions for making a protein. The DNA segments that do contain protein-making instructions are known as exons (green). See image 2550 for an unlabeled version of this illustration. Featured in The New Genetics.

Crabtree + Company

View Media

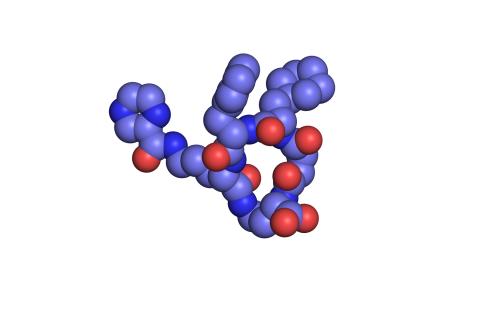

2792: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with hydrogens 03

2792: Anti-tumor drug ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743) with hydrogens 03

Ecteinascidin 743 (ET-743, brand name Yondelis), was discovered and isolated from a sea squirt, Ecteinascidia turbinata, by NIGMS grantee Kenneth Rinehart at the University of Illinois. It was synthesized by NIGMS grantees E.J. Corey and later by Samuel Danishefsky. Multiple versions of this structure are available as entries 2790-2797.

Timothy Jamison, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

View Media

1328: Mitosis - anaphase

1328: Mitosis - anaphase

A cell in anaphase during mitosis: Chromosomes separate into two genetically identical groups and move to opposite ends of the spindle. Mitosis is responsible for growth and development, as well as for replacing injured or worn out cells throughout the body. For simplicity, mitosis is illustrated here with only six chromosomes.

Judith Stoffer

View Media

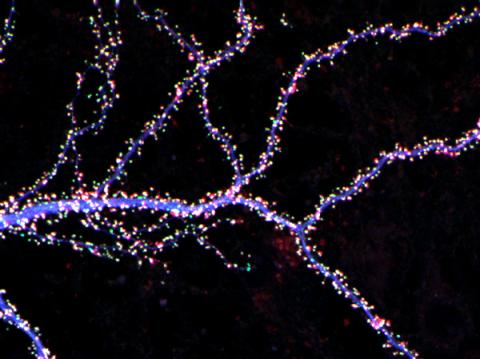

3686: Hippocampal neuron from rodent brain

3686: Hippocampal neuron from rodent brain

Hippocampal neuron from rodent brain with dendrites shown in blue. The hundreds of tiny magenta, green and white dots are the dendritic spines of excitatory synapses.

Shelley Halpain, UC San Diego

View Media

3443: Interphase in Xenopus frog cells

3443: Interphase in Xenopus frog cells

These images show frog cells in interphase. The cells are Xenopus XL177 cells, which are derived from tadpole epithelial cells. The microtubules are green and the chromosomes are blue. Related to 3442.

Claire Walczak, who took them while working as a postdoc in the laboratory of Timothy Mitchison.

View Media

3413: X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor 1

3413: X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor 1

X-ray co-crystal structure of Src kinase bound to a DNA-templated macrocycle inhibitor. Related to 3414, 3415, 3416, 3417, 3418, and 3419.

Markus A. Seeliger, Stony Brook University Medical School and David R. Liu, Harvard University

View Media

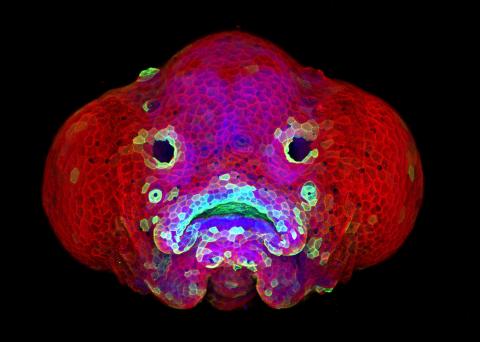

5881: Zebrafish larva

5881: Zebrafish larva

You are face to face with a 6-day-old zebrafish larva. What look like eyes will become nostrils, and the bulges on either side will become eyes. Scientists use fast-growing, transparent zebrafish to see body shapes form and organs develop over the course of just a few days. Images like this one help researchers understand how gene mutations can lead to facial abnormalities such as cleft lip and palate in people.

This image won a 2016 FASEB BioArt award. In addition, NIH Director Francis Collins featured this on his blog on January 26, 2017.

This image won a 2016 FASEB BioArt award. In addition, NIH Director Francis Collins featured this on his blog on January 26, 2017.

Oscar Ruiz and George Eisenhoffer, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

View Media

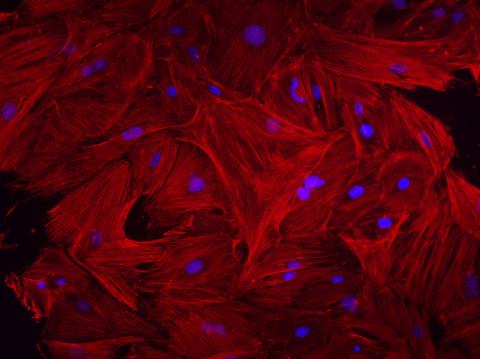

3281: Mouse heart fibroblasts

3281: Mouse heart fibroblasts

This image shows mouse fetal heart fibroblast cells. The muscle protein actin is stained red, and the cell nuclei are stained blue. The image was part of a study investigating stem cell-based approaches to repairing tissue damage after a heart attack. Image and caption information courtesy of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine.

Kara McCloskey lab, University of California, Merced, via CIRM

View Media

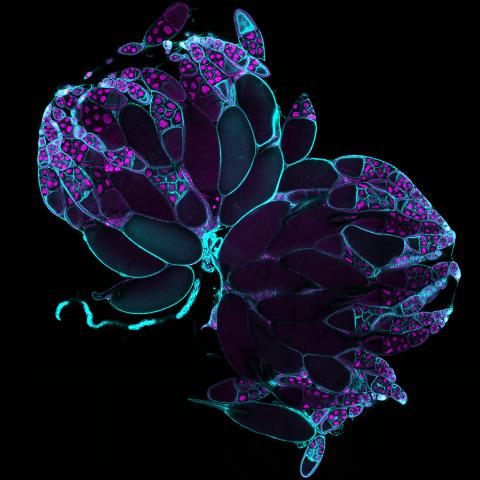

6807: Fruit fly ovaries

6807: Fruit fly ovaries

Fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) ovaries with DNA shown in magenta and actin filaments shown in light blue. This image was captured using a confocal laser scanning microscope.

Related to image 6806.

Related to image 6806.

Vladimir I. Gelfand, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University.

View Media

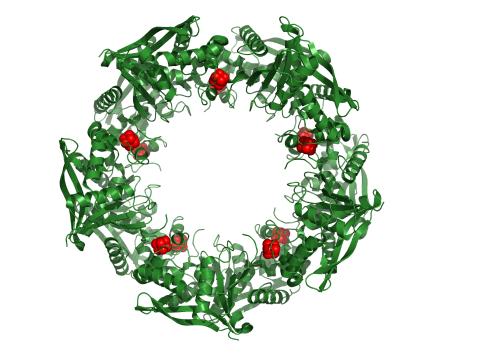

3720: Cas4 nuclease protein structure

3720: Cas4 nuclease protein structure

This wreath represents the molecular structure of a protein, Cas4, which is part of a system, known as CRISPR, that bacteria use to protect themselves against viral invaders. The green ribbons show the protein's structure, and the red balls show the location of iron and sulfur molecules important for the protein's function. Scientists harnessed Cas9, a different protein in the bacterial CRISPR system, to create a gene-editing tool known as CRISPR-Cas9. Using this tool, researchers are able to study a range of cellular processes and human diseases more easily, cheaply and precisely. In December, 2015, Science magazine recognized the CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing tool as the "breakthrough of the year." Read more about Cas4 in the December 2015 Biomedical Beat post A Holiday-Themed Image Collection.

Fred Dyda, NIDDK

View Media

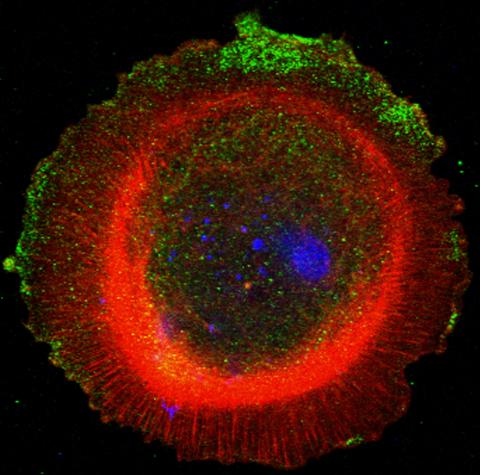

3330: mDia1 antibody staining-01

3330: mDia1 antibody staining-01

Cells move forward with lamellipodia and filopodia supported by networks and bundles of actin filaments. Proper, controlled cell movement is a complex process. Recent research has shown that an actin-polymerizing factor called the Arp2/3 complex is the key component of the actin polymerization engine that drives amoeboid cell motility. ARPC3, a component of the Arp2/3 complex, plays a critical role in actin nucleation. In this photo, the ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells were fixed and stained with Alexa 546 phalloidin for F-actin (red), mDia1 (green), and DAPI to visualize the nucleus (blue). mDia1 is localized at the lamellipodia of ARPC3+/+ fibroblast cells. Related to images 3328, 3329, 3331, 3332, and 3333.

Rong Li and Praveen Suraneni, Stowers Institute for Medical Research

View Media