Sepsis

On this page:

- What Is Sepsis?

- The Importance of Studying Sepsis

- What Scientists Know About the Causes of Sepsis

- NIGMS-Funded Research Advancing Our Understanding of Sepsis

- How Sepsis Is Studied

What Is Sepsis?

Sepsis is a person’s overwhelming or impaired whole-body immune response to an insult—an infection or an injury to the body, or something else that provokes such a response. Sepsis occurs unpredictably and can progress rapidly. In the worst cases, blood pressure drops, the heart weakens, and the patient spirals toward septic shock. Once this happens, multiple organs—lungs, kidneys, liver—can quickly fail, and the patient can die.

The Importance of Studying Sepsis

Sepsis is a serious condition and a leading cause of death in hospitals. Each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), at least 1.7 million adults in the U.S. develop sepsis, and at least 350,000 die as a result. It’s also a main reason why people are readmitted to the hospital.

Unfortunately, there’s no specific treatment protocol for sepsis other than supportive care for the health problems resulting from sepsis and therapy to fight infectious agents that may be the underlying cause. NIGMS funded the inception of the first FDA-approved AI-based sepsis diagnosis algorithm (the Sepsis ImmunoScore). The impact of this exciting new development on sepsis care is yet to be tested in the real world.

More information about the symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of sepsis is available from CDC.

What Scientists Know About the Causes of Sepsis

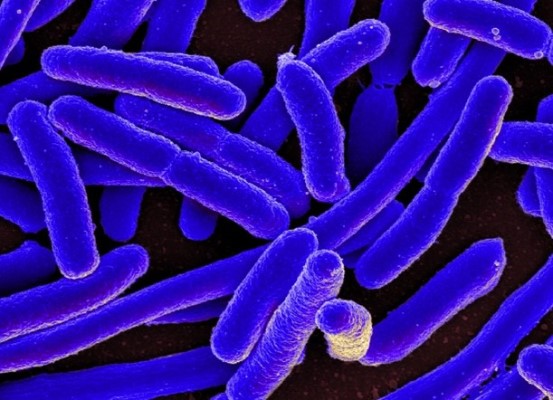

Bacterial infections cause most cases of sepsis. However, viral infections, such as COVID-19 or influenza; fungal infections; or noninfectious insults, such as traumatic injury, can also cause sepsis. Normally, the body releases chemical or protein immune mediators into the blood to combat the infection or insult. If unchecked, those immune mediators trigger widespread inflammation, blood clots, and leaky blood vessels. As a result, blood flow is impaired, depriving organs of nutrients and oxygen and leading to organ damage.

Noninfectious insults can lead to sepsis because they can activate the body’s immune responses just like infections do. Sometimes, the cause can’t be determined, particularly when it’s a bacterial agent and the patient has received antibiotics, which kill the bacteria thus making infectious agents no longer detectable.

The people at highest risk of sepsis are infants, children, older adults, and vulnerable people who have underlying medical problems, have concurrent injuries or surgeries, or are taking certain medications. There are also unknown biological characteristics in the body that may increase or decrease a person’s susceptibility to sepsis and cause some people to decline more rapidly while others recover quickly.

NIGMS-Funded Research Advancing Our Understanding of Sepsis

NIGMS funded scientists seek to answer the fundamental and clinical questions that affect multiple organ systems in the body and are key to improving patient care, including:

- How can clinicians distinguish different kinds of sepsis? Scientists are searching for faster and more accurate tests to diagnose and classify sepsis during its early stages by studying the activity of proteins and other biological chemicals in the blood. These markers can give health care providers information on how severe a case of sepsis a patient has, and whether it might progress, which can help them make decisions about treatment.

- What patient traits are associated with sepsis? Sepsis is difficult to treat for many reasons, including differences in patient physiology and the many possible underlying causes of the disease. Researchers are looking for molecular markers associated with overall sepsis risk and poor long-term outcomes. With the help of systematic data and sample collection from patients with sepsis, NIGMS scientists are studying why some people develop the disease and respond to certain treatment while others don’t—insight that could lead to improved diagnosis, therapies, and outcomes.

- How does the body fight sepsis? Some patients with sepsis resolve inflammation and regain control of their immune response. Certain proteins and other mediators produced by the body are involved in this immune resolution, but it’s unclear why this process breaks down in some patients. Researchers are studying the mechanisms of immune resolution to investigate new therapies that may be useful for controlling sepsis.

- How do health care inequities contribute to sepsis outcomes? African American/Black and Latino sepsis patients experience a lower quality of care and higher rates of complications and death when compared to non-Hispanic White patients. NIGMS researchers are developing interventions to address these issues to improve outcomes and drive reductions in inequities.

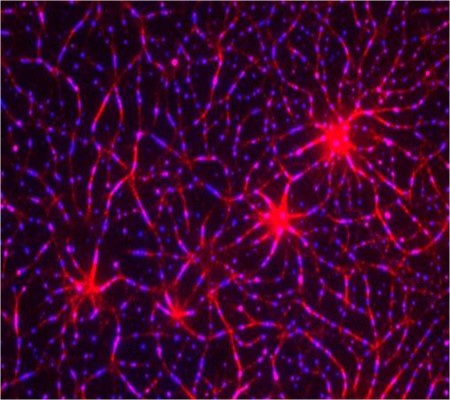

- What causes poor health outcomes in some sepsis survivors? Sepsis can cause illness and death in many ways, even after the underlying trauma or infection and widespread inflammation are under control. Researchers are studying why some recovered patients have a suppressed immune system that leaves them highly susceptible to future infections and whether the nervous system has a role in this suppression. Sepsis can also result in lung injury, muscle wasting, cognitive dysfunction, and impaired blood production.

How Sepsis Is Studied

Scientists are increasingly relying on biospecimens and clinical data collected from sepsis patients to study sepsis. For example, they study patients’ genes and measure biomarkers in patient samples to look for indicators of sepsis outcome or treatment response. Additionally, they create artificial replicas of human organs, such as organoids or organ-on-chips, using human cells to test potential drugs as sepsis treatments. Advances in biospecimen processing and analysis have made many previously impossible tests on human cells possible.

Scientists also use experimental models to study the contribution of certain genes to sepsis. However, it is very challenging to mimic human sepsis, and animals may offer only limited insights for the discovery of treatable molecular targets that can be translatable to humans. Because of these limitations, researchers are searching for new ways to:

- Better mimic the multiple injury and disease pathways that cause sepsis in humans

- Model the medical conditions that increase sepsis risk and syndrome progression

- Develop new therapeutic approaches that sustain the lives of sepsis patients

- Understand the effects of medical complications on sepsis, such as diabetes, cancer, or kidney or liver disease

- Learn what happens in the body after injury and the various medical conditions patients may have that affect sepsis risk and severity by studying patient-derived materials directly

Content reviewed July 2024

NIGMS is a part of the National Institutes of Health that supports basic research to increase our understanding of biological processes and lay the foundation for advances in disease diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. For more information on the Institute’s research and training programs, visit https://www.nigms.nih.gov.