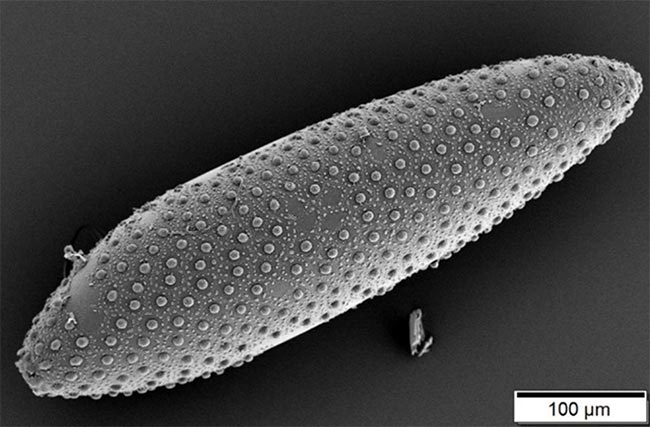

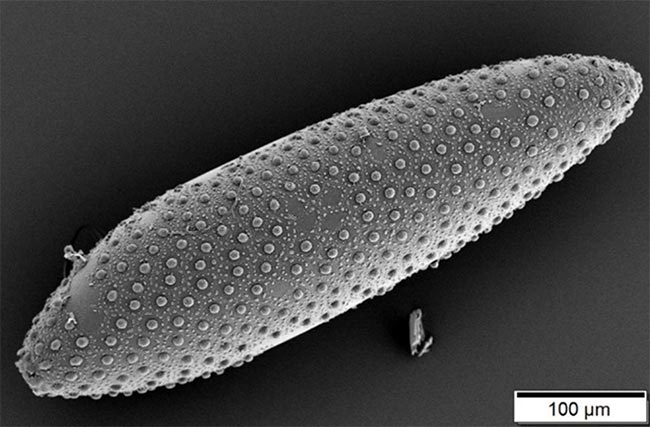

This image shows a mosquito egg. Wolbachia bacteria, which infect many species of insects including mosquitos, move from one generation to the next inside insect eggs. Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Mogana Das Murtey and Patchamuthu Ramasamy, Universiti Sains, Malaysia.

Suppressing insects that spread disease is an essential public health effort, and scientists are testing a possible new tool to use in this challenging arena. They’re harnessing a microbe capable of controlling insects’ reproductive processes.

The microbes, called

Wolbachia, live inside the cells of about two-thirds of insect species worldwide, and they can manipulate the host’s reproductive cells in ways that boost their own survival. Scientists think they can use

Wolbachia’s methods to reduce populations of insects that spread disease among humans.

A Switch to Control Fertility

Wolbachia have evolved complex ways to control insect reproduction so as to infect increasing numbers of an insect species—such as those prolific disease-spreaders, mosquitos. One method

Wolbachia uses is called cytoplasmic incompatibility, or CI. The end result of CI, basically, is that the sperm of infected male insects cause sterility in uninfected females.

Wolbachia that have infected male insects can insert proteins that produce a kind of infertility switch into the host’s sperm. When the sperm later fuses with an egg from an uninfected female, the switch is triggered and renders the egg sterile. If the female is already infected, her eggs will contain

Wolbachia, which can turn off the switch and allow the egg to develop. This trick ensures that more

Wolbachia-infected insects will survive and continue to reproduce, while uninfected ones will be less successful.

Already, some

states

and countries are releasing

Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes into wild mosquito populations that carry disease-causing viruses to test this strategy for insect control. Males carrying a

Wolbachia strain that strongly induces infertility in uninfected females should reduce the numbers of mosquito eggs that mature, leading to fewer mosquitos.

How the Switch Works

Scientists are learning more about the mechanisms behind CI in

Wolbachia-infected insects. Their goal is to develop even more precise tools for limiting the transmission of mosquito-borne diseases, such as Zika and dengue.

Researchers at Yale University, led by

Mark Hochstrasser

, for instance, found a pair of genes in

Wolbachia that seem to be responsible for the infertility switch used by some

Wolbachia strains. One gene,

cidB, makes a protein that clips a piece off other proteins important to insect embryo development. This change hampers a host cell’s ability to function and could cause a fertilized egg to stop developing. The other gene in the pair,

cidA, produces a protein that binds to the

cidB-created protein and can prevent its clipping activity. So, in infected females,

Wolbachia in the eggs can deploy

cidA to keep

cidB from producing sterile eggs.

The Yale scientists have also noticed that different strains of

Wolbachia may rely on different infertility switches. A female insect infected with one strain that has mated with a male infected with a different strain may not have the genes necessary to rescue her eggs from being sterile. The Yale scientists believe this is a result of mutations in the gene pairs that build up over time in

Wolbachia. This is good news for insect control:

Wolbachia-infected insects could still be rendered infertile by a

Wolbachia gene set that generates a different infertility switch.

A New Tool

To learn whether the

cidA-cidB gene pair really is the key to CI, the Yale scientists tested whether this gene pair could cause sterility in insects not infected by

Wolbachia. Using sophisticated genetic techniques, they produced fruit flies (

Drosophila), a widely used research organism, that express the gene pair from birth but are not

Wolbachia infected. When the

cidA-cidB males mated with normal, or wild-type, females, the eggs were sterile. These eggs even showed the same defects in the cell division cycle that happen in

Wolbachia-caused CI. The methods used in

Drosophila would likely work in other insects, including mosquitos.

Applying

Wolbachia’s infertility-switch strategy—and perhaps employing the

cidA-cidB gene pairs responsible for it—could be effective additions to the public health efforts to control disease-carrying insects without causing damage to other wildlife or humans.

This research was funded in part by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under grant R01GM053756.