Maureen L. Mulvihill, Ph.D.

Fields: Materials science, logistics

Works at: Actuated Medical, Inc., a small company that develops medical devices

Second job (volunteer): Bellefonte YMCA Swim Team Parent Boost Club Treasurer

Best skill: Listening to people

Last thing she does every night: Reads to her 7- and 10-year-old children until “one of us falls asleep”

If you’re a fan of the reality TV show Shark Tank, you tune in to watch aspiring entrepreneurs present their ideas and try to get one of the investors to help develop and market the products. Afterward, you might start to think about what you could invent.

Maureen L. Mulvihill has never watched the show, but she lives it every day. She is co-founder, president and CEO of Actuated Medical, Inc. (AMI), a Pennsylvania-based company that develops specialized medical devices. The devices include a system for unclogging feeding tubes, motors that assist MRI-related procedures and needles that gently draw blood.

AMI’s products rely on the same motion-control technologies that allow a quartz watch to keep time, a microphone to project sound and even a telescope to focus on a distant object in a sky. In general, the devices are portable, affordable and unobtrusive, making them appealing to doctors and patients.

Mulvihill, who’s trained in an area of engineering called materials science, says, “I’m really focused on how to translate technologies into ways that help people.”

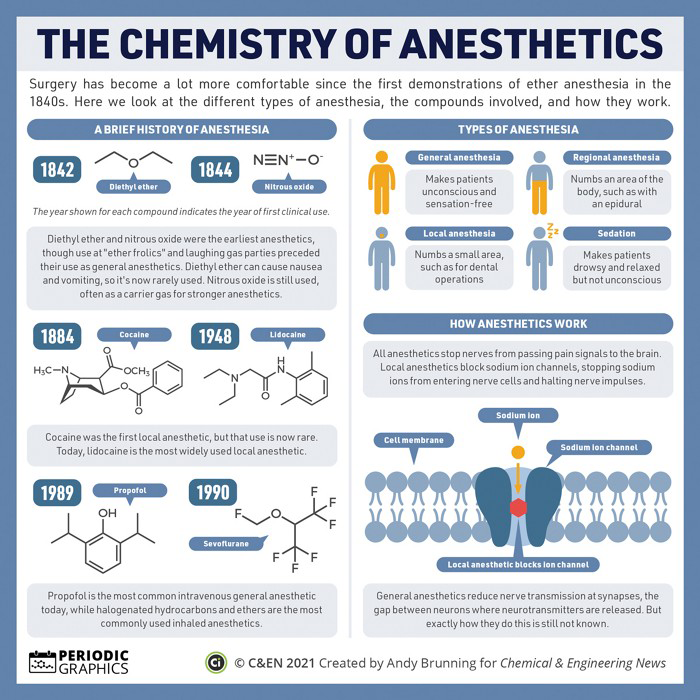

The chemistry of anesthetics has advanced since the 1840s, producing different types of anesthesia depending on the compounds involved. See more chemistry infographics like this one in C&EN’s Periodic Graphics collection.

The chemistry of anesthetics has advanced since the 1840s, producing different types of anesthesia depending on the compounds involved. See more chemistry infographics like this one in C&EN’s Periodic Graphics collection.

Cover of Pathways student magazine.

Cover of Pathways student magazine.

Patients can point to one of the faces on this subjective pain scale to show caregivers the level of pain they are experiencing. Credit: Wong-Baker Faces Foundation.

Patients can point to one of the faces on this subjective pain scale to show caregivers the level of pain they are experiencing. Credit: Wong-Baker Faces Foundation.