2018 Stetten Lecture

Understanding the Source of Regenerative Ability in Animals

Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, Ph.D.

Developmental Genetics and Cell Biology

Stowers Institute for Medical Research

and Howard Hughes Medical Institute

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Research Summary

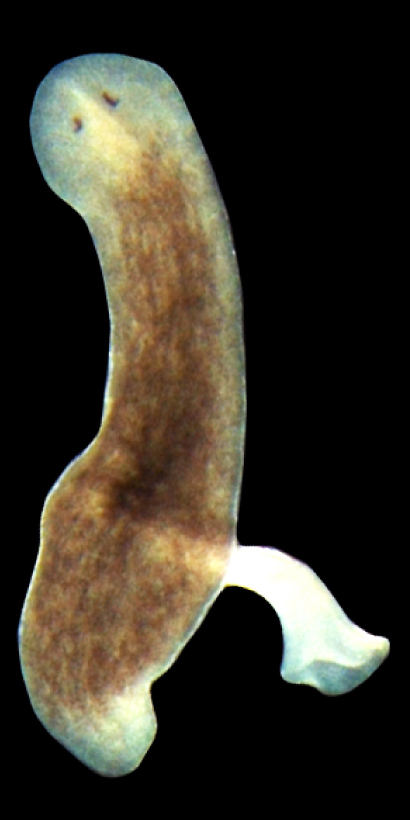

This small worm, shown here with its feeding organ protruding, can accomplish a feat no human has ever achieved. It can regrow any severed body part—including its head. Studies of the worm, called a planarian, might reveal whether it’s possible to boost the ability of humans to repair damaged limbs and organs. Credit: Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado.

This small worm, shown here with its feeding organ protruding, can accomplish a feat no human has ever achieved. It can regrow any severed body part—including its head. Studies of the worm, called a planarian, might reveal whether it’s possible to boost the ability of humans to repair damaged limbs and organs. Credit: Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado.Salamanders and sea stars have an enviable ability to heal. If they lose a limb, it simply regrows. This remarkable ability to restore missing body parts, called regeneration, is the focus of Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado's research.

Sánchez Alvarado is a pioneer in piecing together how regeneration works at the molecular, genetic, and cellular level. A deeper understanding of regeneration might one day reveal ways to boost our own ability to repair damaged or diseased limbs and organs.

For the past 20 years, Sánchez Alvarado has studied a small flatworm called planarian (Schmidtea mediterranea), which he and a colleague obtained from an abandoned fountain in Barcelona, Spain. Their work helped bring this worm to the attention of fellow developmental biologists. Today, it's one of the go-to organisms for studies of regeneration, stem cells, and embryonic development.

Although humble in appearance—less than an inch long, with a cross-eyed appearance—this worm has an awe-inspiring ability. Chop it up into dozens of pieces, and, within two weeks, each piece will become an entirely new organism, complete with a nervous system, digestive system, muscles, and eventually, reproductive organs.

Like many animals, humans have similar regenerative superpowers, but only before we’re born. Once early fetal development is complete, we can no longer regrow highly complex body parts such as complete limbs, an immune system, or a head. We retain merely the ability to replace damaged cells and regrow bits of skin, bone, and liver. If we were planarians, we could grow an entire clone of ourselves from a severed finger.

Years ago, Sánchez Alvarado’s research team set out to discover how planarians retain their embryo-like skills. The team sequenced the worm’s genome; examined the action of countless proteins, adult stem cells, and other molecules; and developed new research techniques that are now widely used by other scientists.

Now, using innovative tools, including single-cell transplantation, the researchers believe they have identified the long-sought source of planarians’ remarkable regenerative abilities—a previously undiscovered type of adult stem cell they call Nb2. They explain their finding in a 2018 article.

In addition to sharing his findings with the scientific community and training young scientists to become planarian researchers, Sánchez Alvarado conveys his excitement about planarians to middle and high school students. He and his colleague Alice Accorsi created an educational project, called The Planarian Educational Resource, Where Cutting Class is Required, that includes hands-on classroom activities for exploring regeneration and stem cell biology.

Born and raised in Caracas, Venezuela, Sánchez Alvarado received his Bachelor of Science in molecular biology and chemistry from Vanderbilt University in 1986, and his doctorate in pharmacology and cell biophysics from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in 1992. He conducted postdoctoral research at the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Department of Embryology. In 2008 he was named a National Academy of Sciences Kavli Fellow, and in 2009 he received a National Institutes of Health MERIT Award. Sánchez Alvarado is also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Latin American Academy of Sciences. He was elected to the National Academy of Sciences this past April.

NIGMS has supported Sánchez Alvarado’s research since 1998 under R37 GM057260.